Posted on Tue., June 19, 2018 by

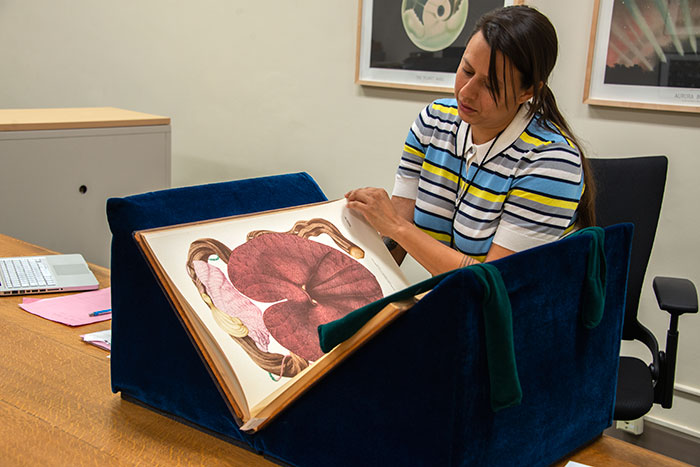

Artist Carolina Caycedo looks through Flora de la Real Expedición Botánica del Nuevo Reyno de Granada, an account of an expedition led by José Mutis and sponsored by Charles III, Charles IV, and Ferdinand VII, kings of Spain. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

In March 2018, The Huntington announced that it was partnering with East Los Angeles College’s Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) for the third year of The Huntington’s /five initiative, inviting noted Los Angeles artists Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. to create new work inspired by The Huntington’s collections around the theme of Identity. The project will culminate in an exhibition that will be on view at The Huntington from Nov. 10, 2018 to Feb. 25, 2019. Carribean Fragoza, a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California, focuses in this post on the artists as they begin to reflect on their research at The Huntington.

Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. begin their residencies at The Huntington by bringing distinct approaches to making new work inspired by the institution’s library, art, and garden collections. Whether instinctive or methodical, intellectual or personal, both artists find ways to enter The Huntington and connect with larger historical narratives.

The gorgeously manicured gardens at The Huntington tend to have an inspiring effect on visitors and, on a smog-free day, perform the breathtaking task of extending its scope to the San Gabriel Mountains. And yet, natural landscapes, whether they are national parks or botanical gardens, can be as curated as any built environment, such as an amusement park or a shopping center. More specifically, they construct an experience for their visitors—one that, at its core, is partly spectacle and illusion.

Carolina Caycedo looks at a photograph detail in an autochrome collection from the 1920s to 1930s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

The spell of illusion is bound to be broken. Or at least interrupted, if you have an artist like Carolina Caycedo on the premises. In a dance performance she recently video recorded, Caycedo interrupted the seamless beauty of The Huntington’s gardens by haunting them with the dancing bodies of brown and black women. Choreographed with Marina Magalhães, the dancers make a ghostly presence that seems possessed, not by the wonders of Western Civilization that surround them, but by the spirit of the Afro-Caribbean water deity Oshun. The video will be part of a multimedia installation that Caycedo is developing and will also include drawings, as well as selected items from The Huntington’s collections.

The presence of these black and brown dancers immediately evokes what is purposefully omitted from such a landscape—labor, for it is the labor of immigrants, slaves, and their descendants that have built the backbone of this nation and its institutions. Caycedo does not turn away from these complicated histories. In fact, she digs into them deeply, with vigor. She is no stranger to the oftentimes tedious task of sifting through the minutia of archival documents. Early in her residency, she was fascinated by a collection of planning documents for the construction of dams along the Colorado River. “What I found interesting,” Caycedo says, “was the rhetoric that was being used to talk about the river as a menace, as something that needed to be controlled. It was like an early shock doctrine.”

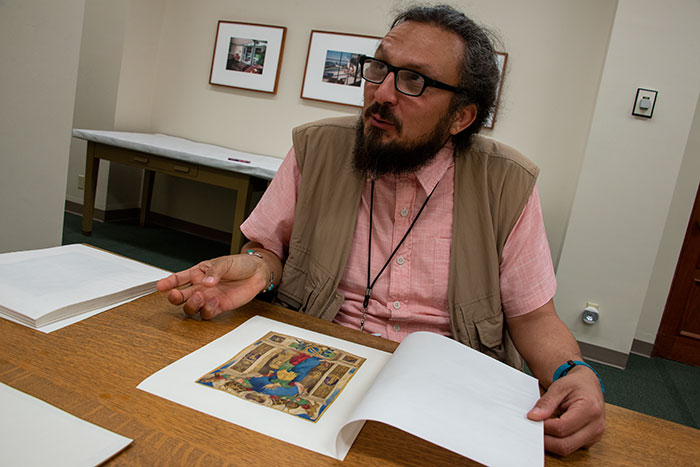

Artist Mario Ybarra Jr. looks through a collection of 15th- and 16th-century Italian illuminated manuscripts. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

Caycedo’s excavation of the relationship between restrained and commodified bodies of water and the bodies of marginalized people of color throughout the Americas is rooted deeply in much of her work. Whether it’s the Magdalena or Xingu rivers in South America or the Los Angeles and Colorado rivers in the western U.S., Caycedo approaches her projects with careful, pointed questions. For her /five residency, Caycedo applies both method and instinct, as she uncovers the internal designs of power that have come to shape the Southern California landscape and the lives of its inhabitants.

For Ybarra, the /five residency is an opportunity to find intersections between seemingly disparate worlds, using his own experiences as points of reference. His residency picks up the thread that he’s been following lately in his artistic practice—an earnest return to the daily practice of drawing.

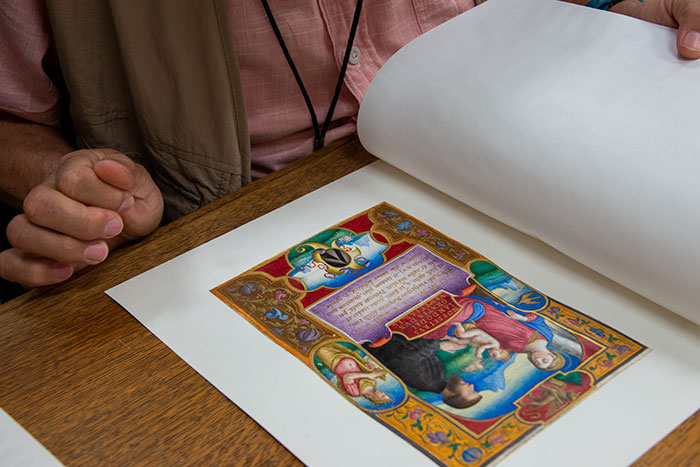

So when, with the assistance of Huntington curators, Ybarra recently browsed through a volume of Renaissance illuminated documents, he was inspired by illustrations of recurring symbols, such as lions and columns that respectively represent justice and power. For Mario, this iconography resonated with images that can be found in contemporary “cholo” culture in Los Angeles. Like the Renaissance monks that performed the painstaking, years-long task of lettering and illustrating hand-made manuscripts, cholos pay comparably close attention to the details of their distinct Old English-inspired calligraphy and images of “firme” (attractive) feather-haired “hainas” (women), smile-now-cry-later comedy/tragedy masks, rosary beads, and tear drops, as well as an array of Aztec-inspired images.

Mario Ybarra Jr. looks at an illustration detail from a collection of 15th- and 16th-century Italian illuminated manuscripts. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

“I’m just letting it all resonate with my own experiences,” says Ybarra. He adds that the Renaissance manuscripts, though many centuries old, seemed familiar. “They made me think a lot about my own life,” he says, and he began visualizing Renaissance symbology in his daily life. For example, he says, when he thinks of his wife and cofounder of Slanguage Studio, Karla Diaz, he pictures her flanked by their two German Shepard dogs as if they were lions. “Karla is like a symbol of justice in my life,” he shares.

Ybarra is also excited about the possibility of bringing The Huntington together more closely with underserved communities. “I would like to see more overlap between The Huntington and East Los Angeles,” says Ybarra. In many of his past projects, Ybarra has often found ways to connect young people of color to the cultural institutions with which he works.

This year’s partnership with the Vincent Price Art Museum, based at East Los Angeles Community College, promises to open new opportunities to bridge these communities. “The Vincent Price Art Museum is committed to presenting groundbreaking exhibitions and connecting with the community in creative ways to make a maximum impact,” says Pilar Tompkins Rivas, VPAM director. “This partnership does just that, expanding our fall programming in terms of concept, theme, and reach.”

Carribean Fragoza is a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California.