The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Ballads Galore

Posted on Thu., Aug. 25, 2016 by

The Woody Choristers; or, The Birds of Harmony, ca. 1775. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

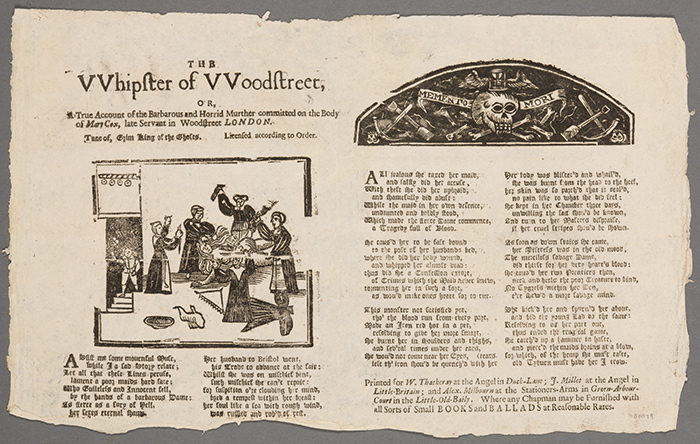

The Summer 2016 Huntington Library Quarterly is a special issue devoted to English broadside ballads from the mid-16th to mid-18th centuries. That was the heyday of this wildly popular medium, which combined song lyrics, often about current events, with stylized woodcut illustrations. Printed on cheap paper and sold by the thousands, broadside ballads told tales of love, murder, political intrigue, and much more—set to familiar tunes.

Guest-edited by Patricia Fumerton, professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, the HLQ special issue was inspired by a conference she convened at The Huntington in April 2014 titled “Living English Broadside Ballads, 1550–1750: Song, Art, Dance, Culture.” As Fumerton explains in her introduction to the issue, the conference had two goals: “to celebrate the inclusion of the Huntington Library’s sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English broadside ballads . . . in the English Broadside Ballad Archive,” of which she is the director, and “mingling scholarly activities with such untraditional functions as ballad singing, fiddling, dancing, and visual encounters with broadside ballad sheets and woodcuts.”

The Whipster of Woodstreet, or, A True Account of the Barbarous and Horrid Murther committed on the Body of Mary Cox, late Servant in Woodstreet London, ca. 1690. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The issue’s nine essays—written through the lenses of art and music history, literary and theater studies, cognitive science and computer-aided bibliographic analysis—convey the multifaceted scholarly approaches current in the study of broadside ballads. These range from close scrutiny of ballad texts and their contexts to explorations of their woodcut illustrations to accounts of their performances on stages, in streets, and in alehouses. One of the essays even delves into the use of computers to date the publication of ballads. The automated tracking of individual pieces of moveable type as they are used and reused helps scholars to map the early print industry.

The Ballad of the Cloak: or, The Cloak’s Knavery, ca. 1701. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the epilogue to the issue, Katherine Steele Brokaw, assistant professor of English at UC Merced, draws striking parallels between broadside ballads and present-day popular media: “The repetitions of today’s popular music are as interpretively complex as ballads were in early modern culture. In the visual memes of the Internet, we see an analogue for the morphing and popularity of ballad woodcuts . . . Lyrics are rarely distributed through cheap print anymore, but they are posted on social media, snatches of them ‘retweeted’ when the words hit home with a listener. Melodies are transmitted digitally, flowing freely through our computers and iPhones, and they are transmuted, too, so that a sampled riff—like the borrowing from Sir Mix-a-Lot in Nicki Minaj’s ‘Anaconda’—creates meaning for its popular audiences because of its familiar melody.”

The Huntington’s collection of broadside ballads, many of which can be viewed online at the Huntington Digital Library, provide us with insight into a past that can seem foreign at first and yet strangely familiar—once we recognize in these songs and images the perennial stories that continue to fascinate us today.

The High-Priz’d Pin-Box, ca. 1750. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can subscribe to the Huntington Library Quarterly or order the Summer 2016 issue from the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kevin Durkin is editor of Verso and managing editor in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.