The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Beautiful Ruins

Posted on Tue., April 28, 2015 by

In Dawn in an Ancient Land, 1871, Anna Blunden depicts the Aqua Claudia, now part of the Park of the Aqueducts on the outskirts of Rome. Unlike Rome’s other ancient monuments, there are no entrance fees and no crowds. As in the 19th century, solitude rewards those who make the trek to see it. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

From Rome’s Colosseum to the temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, ruins hold an enduring fascination for millions of visitors each year. It’s hardly a new phenomenon. From the 16th to the 19th century, many young Englishmen embarked on the Grand Tour, an expedition to Europe’s cultural capitals that served as the culmination of a gentleman’s classical education. Itineraries varied, but much of the journey took place in Italy, with a compulsory stop to see Rome’s classical ruins.

“Glory After the Fall: Images of Ruins in 18th- and 19th-Century British Art” showcases more than a dozen of The Huntington’s drawings, watercolors, and prints from the heyday of the Grand Tour. You can view them in the Works on Paper room on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery through August 10, 2015.

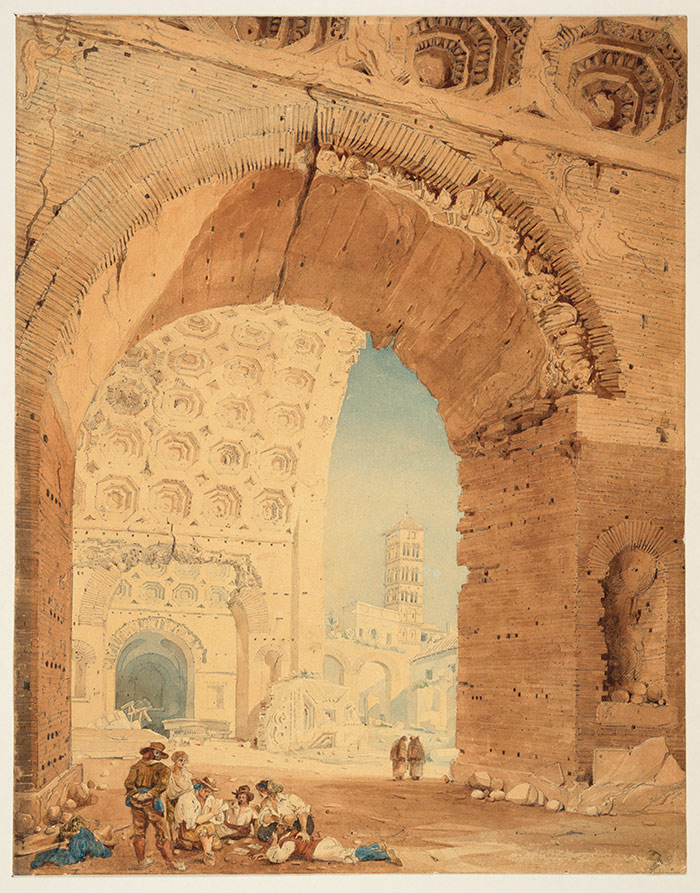

Much of John Goldicutt’s work focuses on the details of ancient Roman architecture. In View in Rome, 1820, he pays special attention to the deep coffers of the towering, fourth-century Basilica of Maxentius. This type of ornamentation was imitated in countless neoclassical buildings throughout Europe. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Classicism dominated English artistic tastes during the 18th and 19th centuries. Aristocratic travelers brought home ancient gems and statues of pagan gods. They also commissioned works of art depicting their favorite ruins, which served as souvenirs from journeys that lasted months or even years. One artist featured in the exhibition is John Goldicutt (1793–1842), a trained architect and skilled draughtsman. Goldicutt was a master of classical subject matter, receiving accolades from the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the pope in Rome.

Goldicutt’s spectacular View in Rome, 1820, depicts part of the Roman Forum, the epicenter of the ancient city and a must-see for any traveler, past or present. Marc Antony and Cicero gave their speeches there, and victorious armies once paraded through its triumphal arches. These exalted moments are distant memories in Goldicutt’s watercolor. Instead, the artist shows peasants seeking shade beneath the remains of the Basilica of Maxentius, the Forum’s largest building. For a Grand Tourist schooled in Roman history, the contrast between past and present must have been especially poignant. The tiny figures add an air of quaintness, highlighting just how far the mighty empire of Rome had fallen.

James Holland (British, 1800-1870), Verona, Amphitheater, n.d., watercolor over pencil. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The incredible demand for classical content made study in Italy a vital component of any artist’s training. Anna Blunden (1829-1915) was among the many artists to establish a studio in Rome. Her exquisite Dawn in an Ancient Land, 1871, shows a popular image of landscapes with ruins. Such drawings were in demand as independent works of art or as studies for large-scale paintings.

Blunden’s serene panorama is interrupted only by an ancient aqueduct that parallels a country road. The mood of her watercolor was echoed by the novelist Charles Dickens, who visited the same site in the mid-19th century. He wrote: “Here was Rome indeed at last…. Except where the distant Apennines bound the view upon the left, the whole wide prospect is one field of ruin. Broken aqueducts, left in the most picturesque and beautiful clusters of arches.”

Many of the sites depicted in “Glory After the Fall” hosted ancient emperors. John Ruskin's Kenilworth, n.d., accommodated an equally illustrious ruler, Queen Elizabeth I, in 1572 and again in 1575. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

British artists also flocked to ruins on their home turf. John Ruskin (1819-1900) created a haunting image of Kenilworth Castle—a palace constructed from Norman through Tudor times in central England. The skeletal remains of the abandoned estate appear melancholy as ivy slowly overtakes them. In addition to his artistic pursuits, Ruskin was a prolific and influential writer. He addressed an array of subjects, ranging from architectural aesthetics to geology to conservation. Ruins allowed him to simultaneously indulge his passions for nature and architecture. For many of the crumbling buildings, the barrier between interior and exterior has almost been eliminated, blurring the distinction between the natural and built environment.

Ruins continue to fascinate artists and travellers because they are enigmatic, intriguing, and embody contradictions. They remind us of the inexorable march of time, yet appear eternal. They are monuments to achievement but act as emblems of loss. These hallowed sites give visitors the opportunity to come face-to-face with the past, reevaluate the present, and contemplate the future.

James Fishburne is guest curator for “Glory After the Fall: Images of Ruins in 18th- and 19th-Century British Art.” He received his Ph.D. in art history from UCLA in 2014 and is currently an adjunct lecturer in Los Angeles.