The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Ben Jonson’s Readers

Posted on Wed., Dec. 7, 2016 by

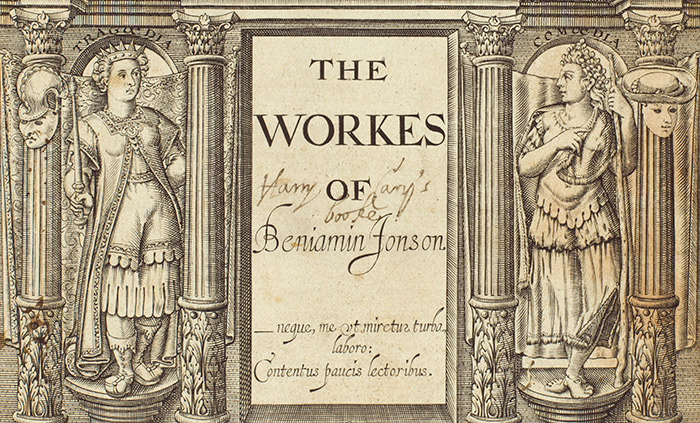

Detail of the title page of The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, showing the inscription of Sir Henry Cary. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The poet and playwright Ben Jonson (1572–1637) was exceptionally concerned with literary posterity. His most ambitious publication was the folio collection of his Works that appeared 400 years ago this year. Through this monumental book, Jonson attempted to ensure that future generations would read and appreciate his plays, poems, and other writings.

How successful was that attempt? How did readers regard the book in the years after it appeared? What do their responses tell us about why Jonson was more celebrated than Shakespeare in the century or so after his death, only to be gradually eclipsed by his great rival? These are among the questions that I was able to explore through The Huntington’s outstanding Jonson holdings—which include more than 30 of Jonson’s 1616 Works, each one unique.

Fortunately for us, the early moderns were not afraid to write in their books. Many of The Huntington’s copies of Jonson’s Works carry in their pages the names of their owners. Sir Henry Cary (1575–1633), for example, inscribed his name right in the middle of the title page (see above), making it clear that the book no longer belonged to its author but to him.

Cary was 1st Viscount Falkland and Lord Deputy of Ireland. His primary interest in the volume may have been the poem of praise to him that begins: “That neither fame nor love might wanting be / To greatness, Cary, I sing that and thee . . .”

![The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, page 840, with note reading “Mary [Jones] Hodge trew hyme Exclently pend by Mr Ben Johnson.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/uploads/2016/10/bjonsonreaders-2.jpg)

The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, page 840, with note reading “Mary [Jones] Hodge trew hyme Exclently pend by Mr Ben Johnson.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Other notable owners of Jonson’s Works in The Huntington’s collection include the essayist and poet Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and the great Victorian poet Robert Browning (1818–89). Most of the copies show evidence of having had multiple owners and readers. Some copies even record such circulation: one, for example, bears the inscription “S. Ruthin my Book Left me by a freind.” There are early female owners and readers, too, some of whom were not afraid to express their opinions. One Mary Jones Hodge, for example, singled out the poem “To Heaven” for praise as a “trew hyme” (see above).

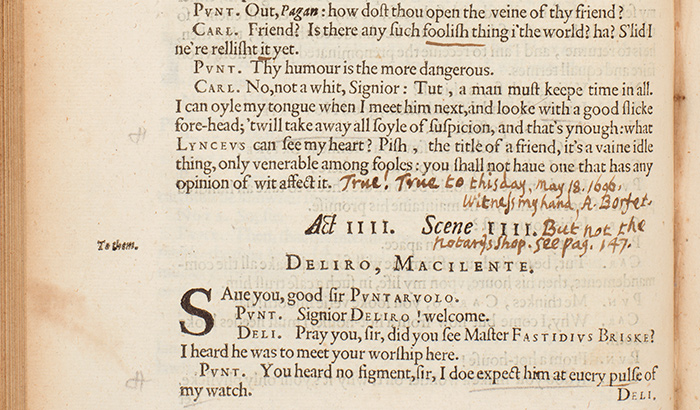

Another reader, Abiel Borfet (1632/3–1710), wrote detailed comments on almost every page of his copy—and this in a book spanning more than 1,000 pages. He adds information, clarifies meanings, and records his responses. At one point, he identifies deeply with a speech about friendship and testifies to this moment of reading by adding his name and the date (see below).

Some of these early readers engage with Jonson’s writings by identifying his sources. Jonson’s writings are steeped in his knowledge of Horace, Ovid, Martial, Juvenal, Seneca, and other great writers of antiquity. Some of his early readers shared some of that knowledge and took it upon themselves to write quotations and references in the margins.

The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, detail of page 142, with note reading “True! True to this day, May 18. 1696. Witness my hand, A. Borfet.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One copy of Jonson's Works contains nearly 250 of these source identifications, an impressive total which may include the contributions of more than one reader. The process of identifying Jonson’s sources was not straightforward. In one instance, you can see that a reader has underlined three lines and written a reference to the poet Juvenal. Then someone—either the same reader at a later time or a second reader—has added the relevant quotation and crossed out some of the underlining (see below). Are we witnessing one reader having second thoughts or two readers disagreeing about which lines exactly constitute the allusion?

Such close engagement requires from the reader what Borfet at one point refers to as “patience.” Borfet and other early readers recognize that a full appreciation of Jonson’s mastery comes from going beyond the immediate enjoyment of his art to having meaningful encounters with the classical texts that he reworks. Growing impatience among later readers may have been one factor in Jonson’s decline in popularity.

Exploring The Huntington’s copies of Jonson’s Works also invites us to reflect upon the nature of books. For early readers, a book such as this was a valuable and durable item. These readers knew that they were the custodians rather than truly the owners of their books, which would in time be sold, given away, exchanged, or bequeathed.

Seeing these copies brings home that a book is not just a vehicle for conveying a text. It is a significant artifact in itself that accretes new meanings as it moves through time and can give intimate insights into the thoughts of generations of readers. That is what sets the printed book apart from Kindles and other modern devices and makes it still so vital.

![The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, detail of page 353, with a marginal note giving a reference to Juvenal’s Satire 7 and a quotation from that poem: “qui facis in parva sublimia carmina [cella,] / Ut dignus venias hederis et imagine macra,” which may be translated as “you that are inditing lofty strains in a tiny garret, that you may come forth worthy of a scraggy bust wreathed with ivy.” The corresponding lines in Jonson’s text, which rework Juvenal’s words to suggest how hard Jonson himself has labored in order to be worthy of literary recognition, have been underlined. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/uploads/2016/10/bjonsonreaders-4.jpg)

The Works of Benjamin Jonson, 1616, detail of page 353, with a marginal note giving a reference to Juvenal’s Satire 7 and a quotation from that poem: “qui facis in parva sublimia carmina [cella,] / Ut dignus venias hederis et imagine macra,” which may be translated as “you that are inditing lofty strains in a tiny garret, that you may come forth worthy of a scraggy bust wreathed with ivy.” The corresponding lines in Jonson’s text, which rework Juvenal’s words to suggest how hard Jonson himself has labored in order to be worthy of literary recognition, have been underlined. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Ben Jonson’s Works at 400 (Sept. 12, 2016)

Jane Rickard is associate professor of 17th-century English Literature at the University of Leeds. She is the author of Writing the Monarch in Jacobean England: Jonson, Donne, Shakespeare and the Works of King James and Authorship and Authority: The Writings of James VI and I .