Posted on Wed., July 6, 2016 by

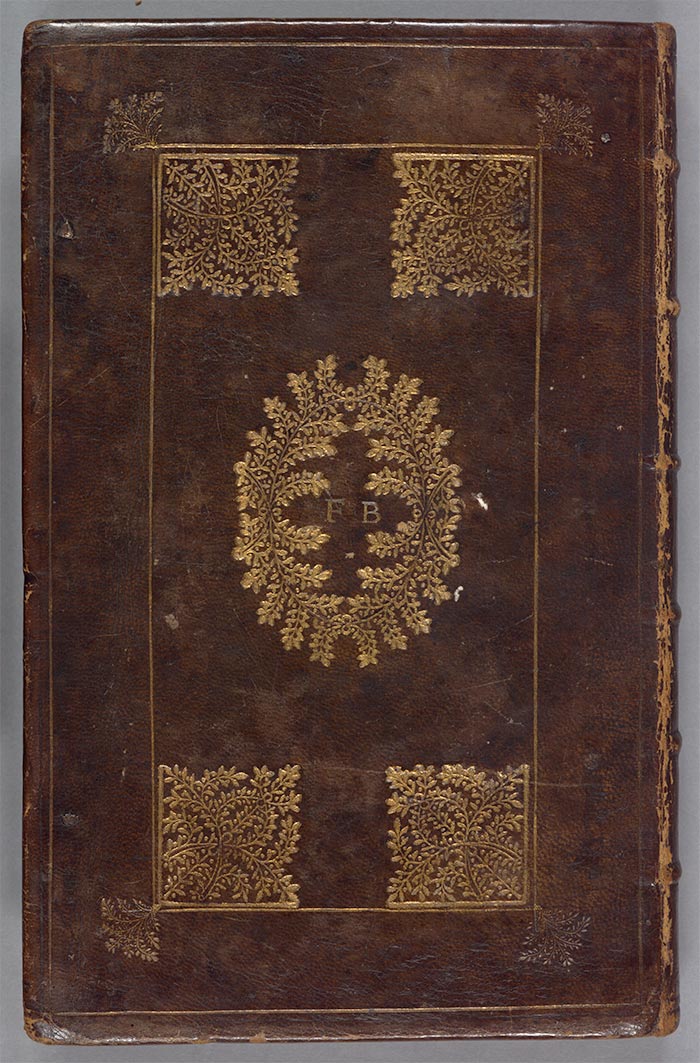

Back cover of William Martyn’s Historie, and Lives, of the Kings of England. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Last February, a bookseller contacted me about a book he had taken on consignment. Its owner believed it came from the library of Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626), the statesman, scientist, and (for a time) alleged author of the Shakespearean plays. My colleague and I agreed to meet at an upcoming book fair for a joint examination.

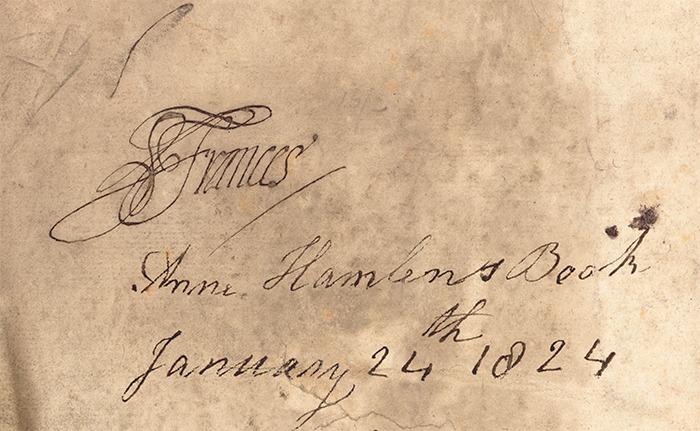

The book turned out to be common enough: William Martyn’s Historie, and Lives, of the Kings of England (1615), of which The Huntington already has two copies. But this one was indeed special, with ornately tooled brown morocco leather covers from the early 17th century and gilt page edges—a luxury-grade custom binding for a person of status. In the middle of the covers were the gold initials “FB,” and inside the front cover was the contemporary signature “Frances.” These features certainly hinted at Bacon, but I felt pretty sure that he wasn’t the owner. Then, as now, “Frances” was the feminine spelling, and Bacon wouldn’t have signed only his first name. The book seemed a bit middlebrow for an intellectual citizen of the world—who probably read more Latin than English—to honor with a top-of-the-line binding. And if it was a presentation copy from the author, why hadn’t the author inscribed it?

Signatures in William Martyn’s Historie, and Lives, of the Kings of England. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

So I explained these and other problems to the bookseller, who had his own doubts about the identification and was satisfied with my analysis. I went on to say that The Huntington might want to purchase the book simply for its attractive binding, and I named a figure. The bookseller relayed my message, and to my surprise the owner agreed to the price. A couple of weeks later, the bookseller returned with the volume, and we completed the transaction in the lobby of the Munger Research Center.

But as I walked back to my office with the new acquisition, a thought stopped me in the middle of the hallway. I opened the front cover and looked again at the “Frances.” I turned to the back and read an inscription on the paste-down that I hadn’t tried to decipher earlier: “The yeare of our Lorde .1623. I did make at ashridge .3. od fine pelobeares .3. pare of a courcer sorte, and seuen pare of a corsser sort, all made at a time.” I didn’t yet know that “pelobeares” meant “pillow-cases,” but when I saw the word “ashridge,” a little current of electricity went up the back of my scalp. No, this was not Francis Bacon’s book; it belonged to Frances Stanley Egerton, Countess of Bridgewater.

Frances Stanley Egerton, Countess of Bridgewater. Oil painting, possibly by Paul van Somer. Private collection at Ashridge House.

The Bridgewater library forms the core of The Huntington’s early English book collection. Growing to 4,400 printed books and 12–14,000 manuscripts during continuous family ownership over three centuries, it was bought en bloc by Henry Huntington in 1917 for a million dollars. Its most illustrious volume, the Ellesmere Chaucer, can be seen today in the Library’s Main Hall exhibition, “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times.”

The founder of the Bridgewater line, Sir Thomas Egerton (1541?–1617), served as Lord Chancellor under King James I, gave financial support to the major authors of his time, and played a crucial role in advancing the professional career of . . . Francis Bacon. In 1600, Egerton married Alice Spencer, the widow of Ferdinando Stanley, Earl of Derby, who had sponsored a theater company when Shakespeare was starting his career. Sir Thomas’s new wife had a daughter from the earlier marriage, whose name was Frances.

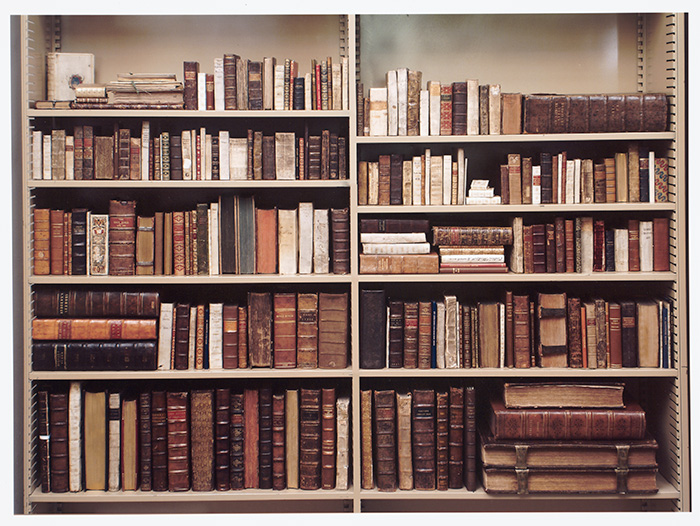

Heidi Brayman Hackel’s reconstruction of Frances Stanley Egerton’s collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In a typical act of dynastic consolidation, the couple arranged for Frances to marry Sir Thomas’s son John by his previous marriage. In 1604, father and son acquired a country estate in Hertfordshire. That is the “Ashridge” in our book’s inscription. In 1617, after the death of his father, John Egerton became the first Earl of Bridgewater, making Frances the Countess of Bridgewater. That is the “FB” on our book’s covers, and that is her autograph inside.

The Countess has star status in the history of books and reading because a contemporary handwritten catalog of her books survives, compiled in 1627–32 and titled “A catalogue of my Ladies Bookes at London.” Lists of women’s libraries are like gold nuggets in the historical record; only five others prior to 1627 have been located, and the Countess’s collection, numbering 241 titles, evidently outstripped all of these. Our new copy of Martyn’s Historie appears as the 16th item in that inventory. For some reason, many of her books were apparently dispersed before Huntington bought the family library. In 2005, Heidi Brayman Hackel, associate professor of English at UC Riverside and a reader at The Huntington, created a physical reconstruction of Frances Stanley’s collection, using the Countess’s known copies where possible and otherwise substituting Bridgewater family or other copies.

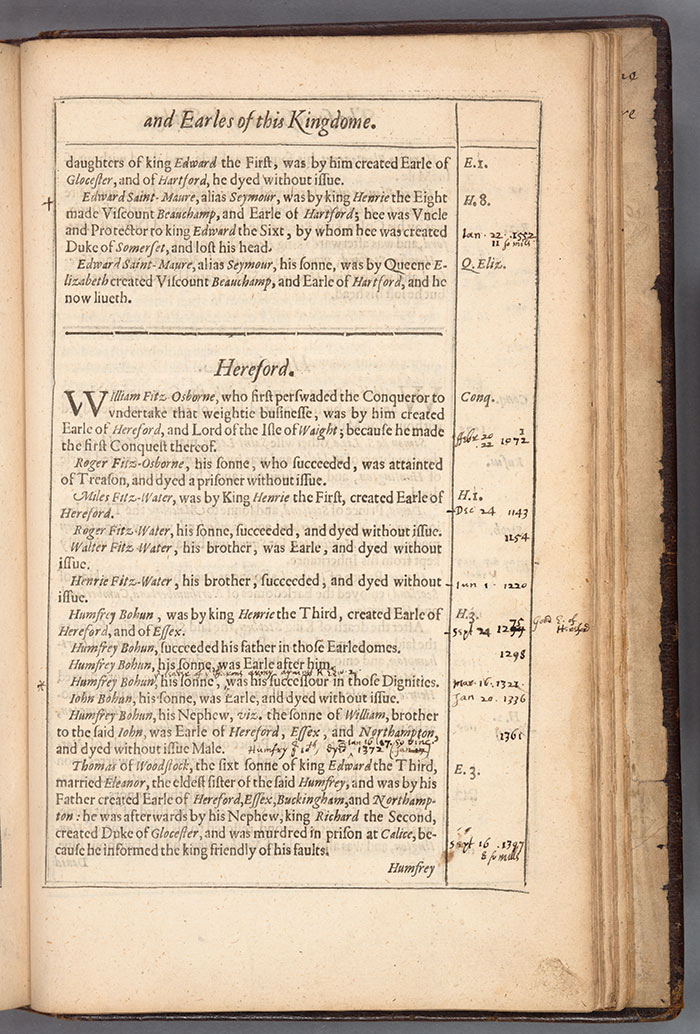

Annotations in William Martyn’s Historie, and Lives, of the Kings of England. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Disappointingly, most of the Countess’s books that have been identified bear no annotations to show how they were used. Our new book is an exception. Martyn’s Historie concludes with a 70-page list of dukes and earls with brief biographies. In the Countess’s copy, an early reader has annotated this section with additional facts, highlighting the individuals who met sticky ends with asterisks for “slaine” and crosses for “beheded.” Who had this morbid interest? Was one of the Bridgewater clan contemplating the hazards of nobility? Other annotations in the book, most of undetermined authorship as yet, will attract scholars studying readership in the early modern period.

After a two-century walkabout, Frances Stanley’s book has rejoined the Bridgewater family library. The first thing I did after that tingling realization was to email Heidi Hackel. She came to my office, saw the book on the table, and cried, “Frances, you’ve come home!” Indeed, considering the importance of the Bridgewater library to The Huntington’s collections, this book’s provenance is better than Bacon.

Editor’s note: In response to a couple of inquiries that came in after this post was published, we want to note that the curator did inform both the dealer and the seller of his findings, and he offered to increase the purchase price substantially based on the new identification. (His offer was gratefully accepted!)

Stephen Tabor is curator of early printed books at The Huntington.