The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Beyond George Washington

Posted on Fri., Feb. 18, 2011 by

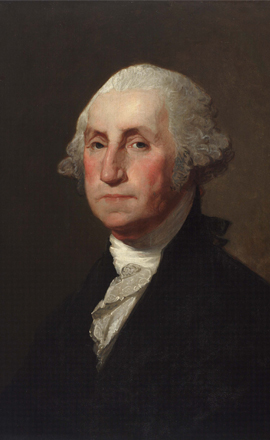

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755-1828), George Washington (detail), 1819, oil on canvas, on view in the Huntington Art Gallery. © The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

It's hard for many people to get past the familiar image of George Washington that appears on the dollar bill. Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) painted several iconic portraits of our first president, some of which were used in engravings, so many reproductions are in reverse of the oil paintings. The Huntington has two of the Stuart paintings—one in the dining room of the Huntington Art Gallery and the other in the Scott Galleries of American Art.

Next to the Stuart painting in the Scott Galleries is a full-scale portrait of Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army after the Battle of Princeton, a decisive victory over the British that took place on Jan. 3, 1777. Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) executed a portrait that he went on to copy many times, as did countless other artists. The Huntington's version is probably by a French artist. Another smaller and slightly altered copy of it hangs to the left, this one by Peale's nephew, Charles Peale Polk.

If you walk into the Library's main exhibition hall, you'll encounter yet another rendering of Washington—a life-sized bronze copied from the famous original by French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), which some have called the truest likeness of our first president, although others would argue that the Peale images are worthy of that distinction.

"Peale knew Washington best of all of the artists who depicted him because he fought with him," says Kevin Murphy, the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington.

Three portraits of Washington in the Scott Galleries of American Art. © The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington's many rare books and manuscripts related to Washington give further dimension to him and have gone on display in great number on more than one occasion, including last year's exhibition "A Clash of Empires: The Seven Years' War and British America," curated by Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American Manuscripts at The Huntington.

But if you wander through the manuscript and rare book displays currently on view in the hall, you'll still find glimpses of Washington. In one autographed document from 1749, a 17-year-old Washington drew up a survey for 400 acres of land on the Lost River in Virginia. A few years later, in 1754, he was already a military leader and wrote in his journal about an encounter with French soldiers in Ohio. Says Tsapina: "The governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, used the published edition of the journal to drum up support for a military action against the French. So it was used, in effect, as a piece of political propaganda." The display cases also include a facsimile of Washington's chart of the Continental Army in 1776.

And yet there is far more to Washington than Washington. Historian T. H. Breen recently delivered a lecture here in which he invited the audience to go beyond the Founding Fathers to discover the impact of ordinary Americans in helping to create the climate for successful revolution. Ultimately, says Breen, the accomplishments of leaders like Washington came from the power of the people. Breen's talk about his book American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People is available for download from iTunes U. Breen is the William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern University.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.