Posted on Mon., March 13, 2017 by

The title page of Edward Jenner’s An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolæ vaccinæ, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the cow pox, 1800 (second edition). Jenner relies on the Roman poet Lucretius to introduce his medical method: “What more than our senses can there be to distinguish truth and falsehood?” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I’ve been tracking two people in the archives of the Huntington Library whose careers reveal surprising parallels.

One is William Wordsworth, the Romantic-era Lake District poet who made a career of dancing among daffodils and touring the rural reaches of late 18th-century England. The man became almost more important than his poetry; we remember him as the quintessential English poet with global reach, even if we can’t recite a single line from the Prelude.

The other is physician and scientist Edward Jenner, a name that might prompt a guilty and surreptitious click to Wikipedia. In 1798, he published An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolæ Vaccinæ, the foundational work that set the stage for modern vaccination and immunology.

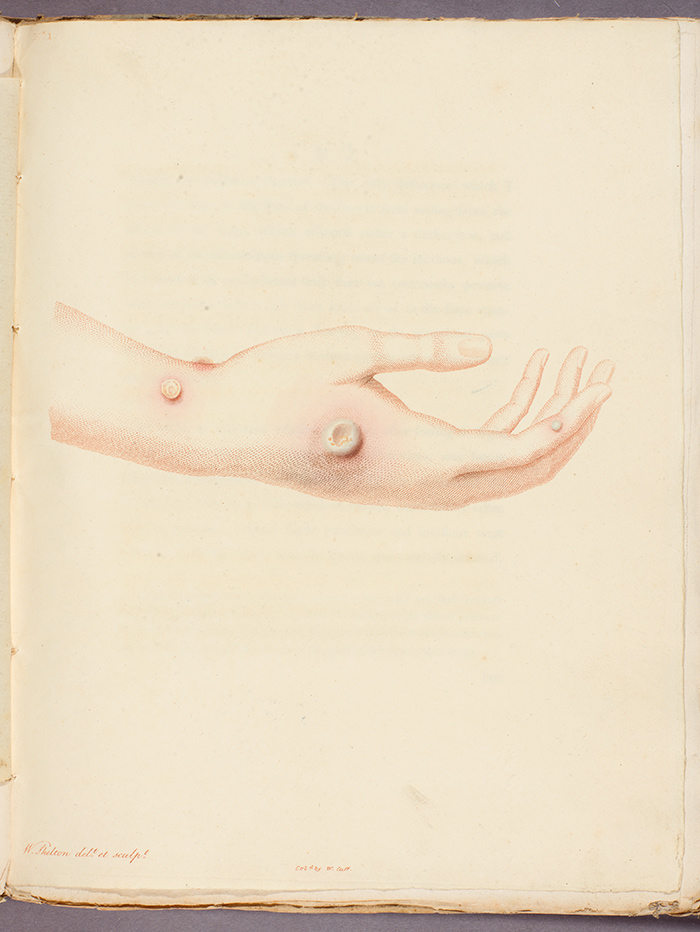

Illustration of four cowpox pustules modeled after the case of milkmaid Sarah Nelmes in Edward Jenner’s Inquiry. The large pustule on the hand and the two small ones on the wrist were all the result of an infected “scratch from a thorn.” The pustule on the forefinger (modeled after a different patient) shows the infection at an early stage. The cowpox pustules were used to develop a smallpox vaccine. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Before Jenner’s Inquiry, smallpox inoculation, or variolation, was the accepted practice to prevent the frequently fatal consequences of smallpox. It was an imperfect procedure that often led to the full-blown disease rather than immunity, but the speckled monster was so feared that many doctors proposed the treatment despite the risk. In the 18th century, smallpox was responsible for an estimated 10 percent of all adult deaths and one third of infant mortalities. And more than half the population bore the disfiguring scars of the disease. Jenner’s Inquiry couldn’t have come soon enough.

A poetic icon and a health hero might have precious little in common today, but in the Romantic era, disciplinary boundaries, when they existed at all, were treated more like suggestions. The surgeon who first described the “shaking palsy,” James Parkinson (1755–1824), also found time to write about his interest in dinosaurs. Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829), eminent chemist of the Royal Society, tried his hand at rhyming verse. To speak of a poet laureate and a conqueror of disease in the same breath, then, isn’t as strange as we might think.

The title page of Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published anonymously in 1798. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

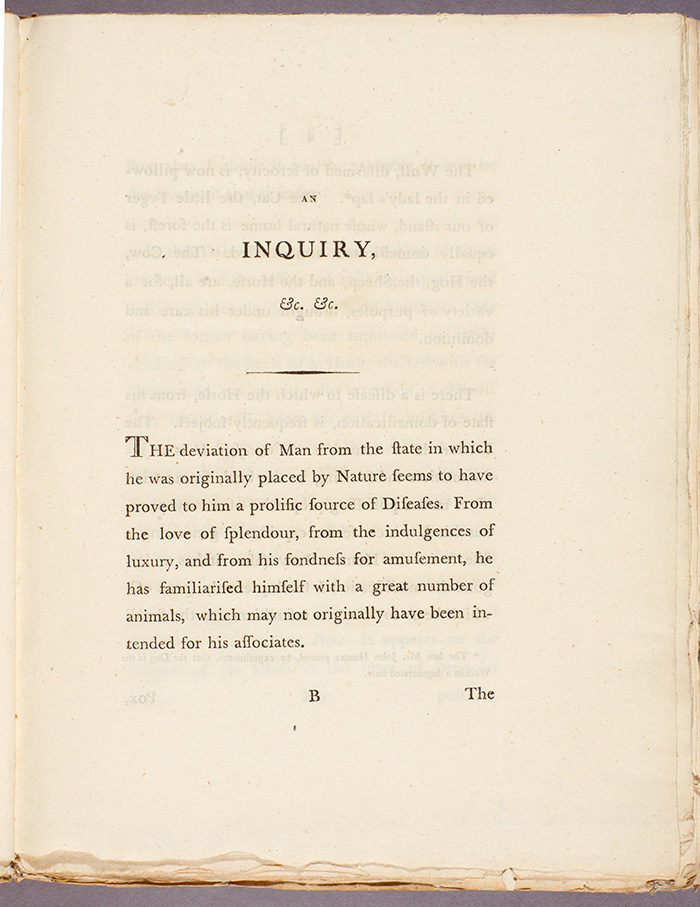

In fact, Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads and Jenner’s Inquiry, published in the same year, shared a common form: the medico-literary rural case study. Wordsworth’s lyrical balladeers canvassed the countryside for rustic wisdom from unlikely sources: an idiot boy, an old huntsman, a mad mother, and an aged beggar. Jenner cataloged cases from dairymaids, servants, and gardeners to track diseases, which he believed originated in a “deviation of Man from the state in which he was originally placed by Nature.” Independently, and at the same time, Wordsworth and Jenner articulated the seminal, capital-R Romantic argument: the best medicine was to go back to nature.

As they grew older, Wordsworth and Jenner both changed. The rustic Lake poet hardened, turned against his radical politics, and sold out to become the 11th British poet laureate. Jenner, meanwhile, abandoned the Gloucestershire countryside for urban, state-sponsored fame. He became fiercely protective of his hard-won reputation, leaving behind the rustic wisdom of the natural world for the heated politics of public health.

The first page of Edward Jenner’s Inquiry. In a particularly Romantic mode, Jenner blames “love of splendor,” “indulgences of luxury,” and “fondness for amusement” for the proliferation of disease. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For example, in a letter that I discovered here at The Huntington, Jenner expresses outrage to his colleague William Clement about upstart vaccinator John Walker, who did not follow the principles set down by Jenner and had threatened to start his own vaccination institute. Having first advised Dr. Clement to ignore that “Vulture Walker,” Jenner changes his mind at the end of the same paragraph, directing his friend to punish fully Dr. Walker’s insolence. For Jenner, proper vaccination procedure was just not up for debate.

I find it useful to compare the trajectories of these two Romantic-era lives because they tell us a lot about the nature of success. Wordsworth is remembered as the heroic father of vernacular English poetry and Jenner as the conqueror of smallpox. (Jenner has been conscripted into a triumphalist narrative of modern medicine and was even inducted into MetLife’s early 20th-century series of “Health Heroes.”) Like Wordsworth, however, Jenner was once a humble rustic wanderer, and that’s exactly what led him to his remarkable discovery.

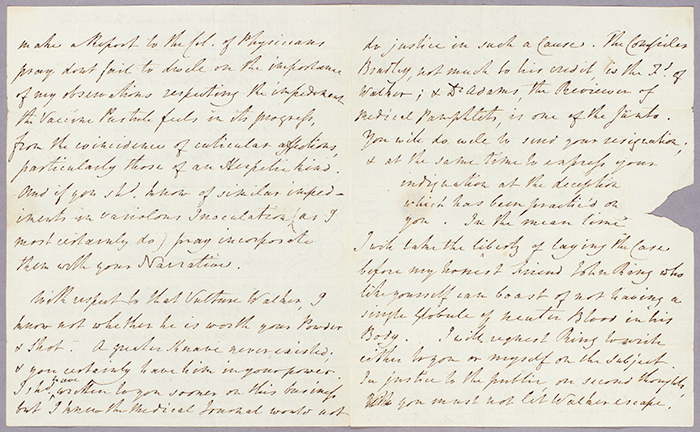

The second and third pages of Edward Jenner’s letter to his colleague William Clement about upstart vaccinator John Walker, Dec. 19, 1807. At the beginning of the second paragraph (left), Jenner writes: “With respect to that Vulture Walker, I know not whether he is worth your Powder & Shot.” By the end of the same paragraph (right), he’s changed his mind: “on second thought, you must not let Walker escape.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Click image to enlarge.

My current book project explores the messy medico-literary culture of Romanticism that allowed a Wordsworth and a Jenner to flourish. Vaccination, in my view, was not a triumph of the singular genius but of a cultural landscape that made such a discovery possible.

We enjoy the gripping narrative of success, but we must also remember the twists and turns that got us there. After his Inquiry, Jenner spent the rest of his life in the business of polishing his clinical narrative of uninterrupted rational progress, purging the detours, mistakes, and dead ends along the way.

Recently, the cracks in this clinical façade have begun to show. The anti-vaccination movement is back with a vengeance, and the two sides hardly speak the same language: medical authorities can only wag their fingers at public ignorance, while anti-vaxxers cling to their misguided sense of being in the right. If we could remember the productive dialogues of Wordsworth among beggars and Jenner among milkmaids, before their overshadowing successes, we might find some common language after all.

Front cover of a 1928 MetLife brochure featuring Edward Jenner as a “health hero.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Fuson Wang is assistant professor of English at UC Riverside and a 2016–17 Fellow in the Huntington–UC Riverside Program for the Advancement of the Humanities.