The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Born and Raised in Hawai’i

Posted on Mon., May 8, 2017 by

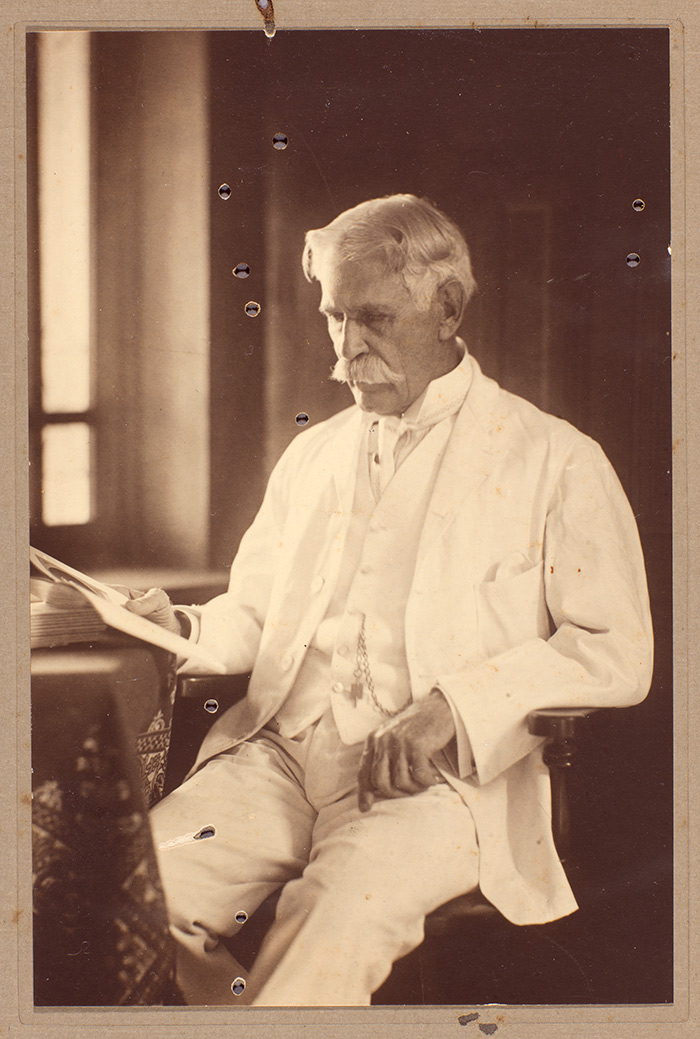

Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839–1915). Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the greatest joys for historians doing archival research is the opportunity to become lost in someone else’s world. I had this experience during my recent fellowship at The Huntington as I delved into the papers of Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839–1915), a physician, ethnologist, and author of several books on Hawaiian mythology.

I’d suspected Emerson would be a figure of interest in my research into the religious dimensions of American empire building in the Pacific Ocean in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. What I didn’t anticipate was how the richness of his personal papers would draw me in. As I got to know Emerson, I saw a complex figure emerge whose published works did not appear to fully represent the thoughts of the man himself. This complexity suggested something broader about the uncertainties of American engagement with the Pacific in this period.

Emerson was born in Waialua on the Hawaiian island of Oahu to Ursula Emerson and the Reverend John S. Emerson, who arrived from the United States as missionaries in 1832. Educated first at Punahou, the school for mission children in Honolulu, Nathaniel then studied at Williams College in Massachusetts, served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and trained as a medic at Harvard and in New York. He returned to Hawai‘i in 1878, ultimately taking up the presidency of the Hawaiian Board of Health.

Title page of Emerson’s book Unwritten Literature of Hawaii: The Sacred Songs of the Hula, published by the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology in 1909. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Despite his medical expertise, Emerson’s greatest passion was for the Hawaiian past, and he pursued this interest with vigor from the end of his tenure at the Board of Health in 1890 until his death. In particular, he was a keen collector of Hawaiian folklore, asserting the need to gather and commit to paper fragments of oral tradition before the onslaught of “civilization” transformed Hawai’i beyond recognition. Emerson published three major works on the subject of Hawaiian tradition, beginning with a translation of Hawaiian historian David Malo’s work in 1898, released under the title Hawaiian Antiquities. Next came Unwritten Literature of Hawaii: The Sacred Songs of the Hula in 1909, followed by Pele and Hiiaka: A Myth from Hawaii shortly before his death in 1915.

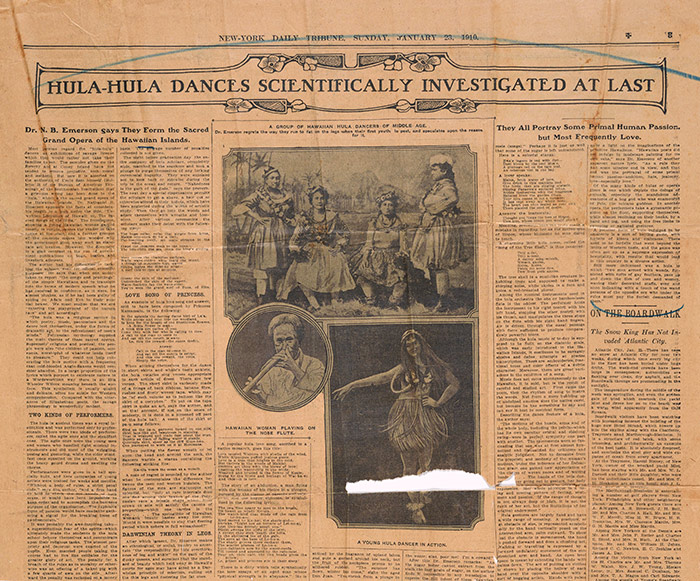

Through his ethnological studies of the Hawaiian people, Emerson was able to enhance his reputation as a man of science. In particular, Unwritten Literature of Hawaii was picked up and published by the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, leading one reviewer in the New York Daily Tribune to proclaim that Emerson’s conclusions were “asserted on the authority of Uncle Sam himself.” Emerson’s books suggested that he was dispassionately to add to the sum of the world’s knowledge about indigenous peoples. But what struck me as I pored over his unpublished essays, literary work, and correspondence was that in private he appeared to understand Hawaiian tradition in rather more poetic terms.

Detail of an article about Emerson’s book Unwritten Literature of Hawaii in the New York Daily Tribune, Sunday, Jan. 23, 1910. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

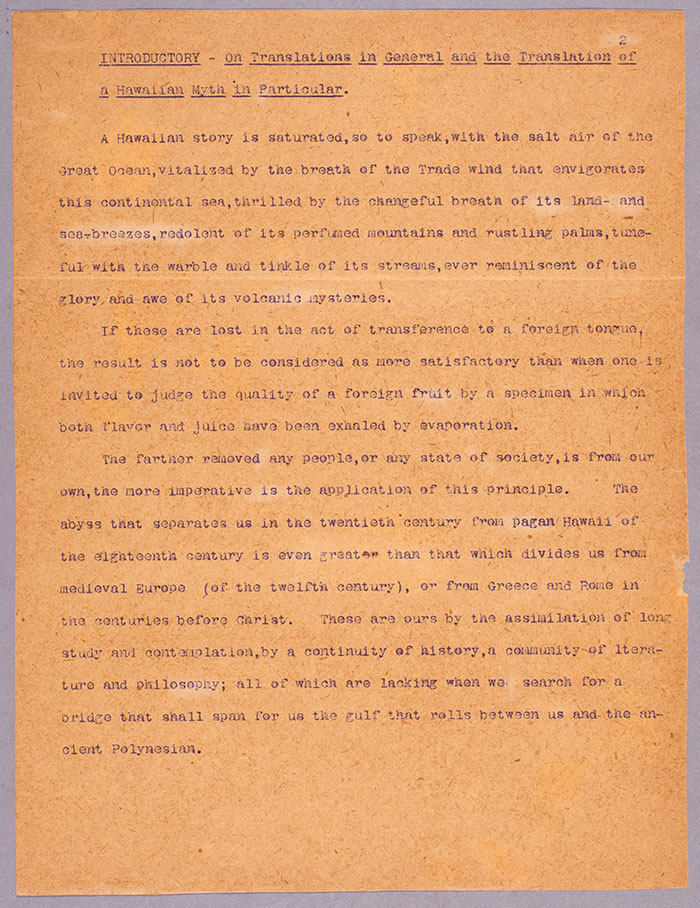

I got the sense that Emerson felt somewhat alienated from modern American life and was looking for an outlet through which he might express his sense of connection to the natural beauty of the land of his birth. He disdained urban life, prudish and inflexible moral codes, and the ignorance of Americans regarding Hawai’i, even claiming that “I have been ready at times to exclaim with Wordsworth: ‘Great God! I’d rather be a pagan.’” He meanwhile celebrated Hawaiian tales as being “saturated with the salt air of the Great Ocean,” “redolent of perfumed mountains and rustling palms,” and “reminiscent of the glory and awe of volcanic mysteries.” Emerson’s private ambition to be a short-story writer failed to bear fruit, but he identified in Hawaiian tradition a source for the words which he could not find. He styled himself as mediator between Hawaiians’ responses to the landscape around them and the written word.

Given Emerson’s obvious romanticism, it is interesting that his conclusions should end up being accepted as scientifically authoritative. His insistence on the primarily poetic, literary nature of Hawaiian tradition obscured insights into the ways in which Hawaiians understood their island world. For them, traditional accounts were profoundly connected to the narration of Hawaiian history and had ongoing resonance in contemporary politics and society.

By denying the relevance of Hawaiian lore as a historical source, Emerson partook in the efforts of his fellow mission children and grandchildren to undermine the indigenous population and to lay their own claims to dominance. This position would become most visibly expressed by the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893 and the annexation of the islands to the United States in 1898.

Emerson and other mission descendants also shared an uncertain identity, caught between Hawaiian birth and American “civilization.” The fact that these architects of American empire in Hawai’i experienced such uncertainties suggests to me that the foundations of American empire in the Pacific were often shaky. In the end, it made me wonder if we should understand American imperialism as something other than all-powerful or inevitable.

A page of Emerson’s unpublished and undated essay “General Remarks on Translation.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Tom Smith is a doctoral candidate at the University of Cambridge and a 2016–17 Arts and Humanities Research Council–Huntington Fellow.