The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Brave New (and Old) World of Data

Posted on Thu., Nov. 17, 2016 by and

Edison photographer Doug White’s overhead shot of three computer key punch operators creating data entry cards, undated. Southern California Edison Archive. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Data, made up of units so uniform as to be, almost by necessity, boring, unite to form collectives of information in a data-driven world that is recognized now as exciting, sexy, and consummately modern. And not for the first time, we must add. At least since the rise of print culture, the thrill of data has been linked to brave new technologies.

An international group of historians will consider the promises, fears, practices, and technologies for recording and transmitting data from the 18th century to the present—as well as their implications for the lives of citizens and subjects—during the “Histories of Data and the Database”conference on Nov. 18 and 19 in Rothenberg Hall.

We will follow the history of data from the indexing systems and encyclopedias in early modern Europe, to the printed forms and filing schemes of the late 19th century, to the advent of electronic computers in the last years of the second millennium, which have managed such increasingly large amounts of data that their output must now be stored in an even newer technology—the Cloud.

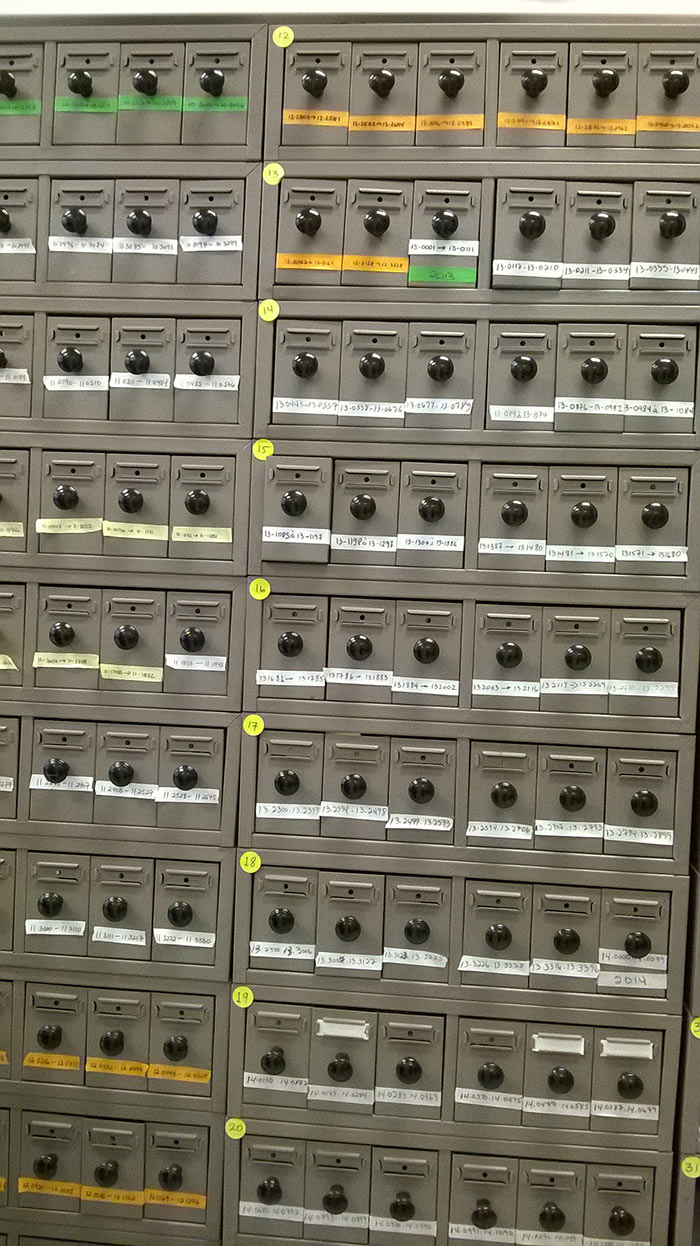

Slide filing cabinet, biomedical laboratory, 2016. Photo by Soraya de Chadarevian.

Behind all the data, in one form or another, are people. Indeed, well into the 20th century, humans performed data analysis (and, often enough, they still do). Data analysis became a specialty, and even an occupational category—the so-called “computer.” Up until about 1860, this was usually a man, and thereafter was more likely a woman. Astronomers, archeologists, and medical officers depended on such calculators, as did business firms and government offices. Human heredity, one of the more illustrious objects of data manipulation in the genomic era, was already a data science in 1850.

Until 1860, most censuses relied on large sheets of paper carried from door to door by officials who filled out a single line for each household. Many other enterprises, such as observatories, hospitals, government offices, and merchant vessels kept records in bound books. Sometimes their data were simply entombed there, but some of these records were routinely consulted or even combined with financial statements or maps to summarize or reveal patterns.

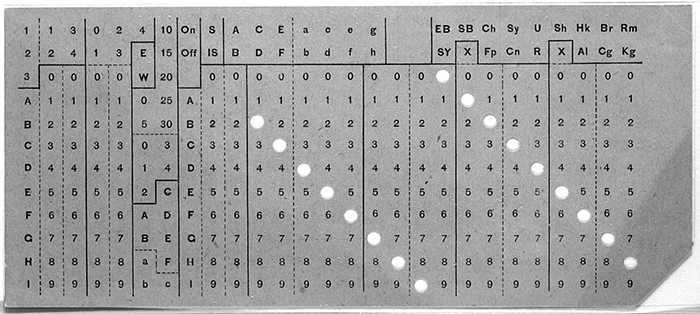

By 1900, those managing the Prussian census were sending out crates of large cards to Berlin homeworkers to sort cards manually. Using movements like those of a dealer in a casino to sort cards, these workers helped officials create tables of data that combined up to six different variables. After completing the first round, the census officials often sent the cards out again to be sorted in a different way to display the relations among a different set of variables. From their inception, filing systems with index cards brought unprecedented suppleness to data work.

Hollerith punched card, 1895. Library of Congress.

In our digital era, data appears to be immaterial, floating somewhere, or even nowhere. In truth, our modern data deluge depends on great banks of computers and consumes vast quantities of energy. Such data does not melt away, at least not so long as the air conditioning continues to function.

The incomparable increase of data in our own age also includes more waste than ever. The Big Data Hall of Fame for the early 21st century will be filled with heroes who worked out algorithms for processing data from social media to manage advertisements in such a way that seven in a thousand recipients will click the desired link, rather than a mere four or five.

One of the tasks of history is to identify the sources of what enthusiasts proclaim to be utterly new and revolutionary. Yet history is about change and novelty rather than stasis. The wonderful world of data combines the ethereal and the mundane, material things and lofty theories, breakthroughs and bureaucracy. Data seems to beg to be made routine, yet it regularly undermines known rules and conventions. And while seemingly impersonal, it has, in fact, a very human history.

You can read more about the conference program and registration on The Huntington’s website.

Theodore Porter is Distinguished Professor of History and Peter Reill Chair in European History at UCLA.

Soraya de Chadarevian is professor of history with a joint appointment in the UCLA Department of History and the UCLA Center for Society and Genetics.