The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Chinese American Advocate, Y.C. Hong

Posted on Tue., Dec. 15, 2015 by

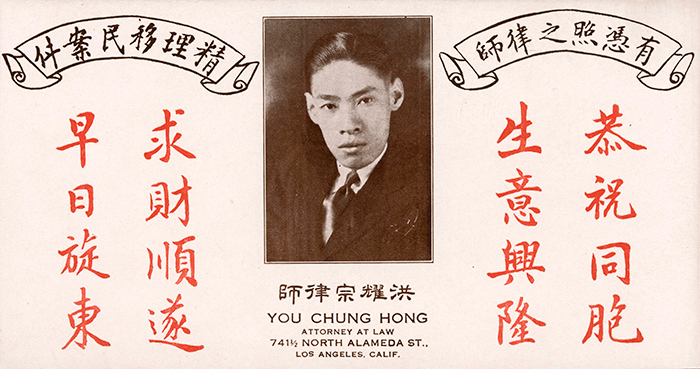

Y.C. Hong’s business card/business flyer, ca. 1928. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For a period of decades spanning the late 19th century to well into the 20th century, Chinese immigrants faced huge obstacles entering the United States due to the Chinese Exclusion Act. The law, in effect from 1882 to 1943, was the first instituted to stop a particular ethnic group from immigrating to this country.

American-born You Chung (“Y.C.”) Hong (1898–1977) was one of the first Chinese Americans to pass the California Bar, and, as a prominent immigration lawyer, worked tirelessly for equal rights for Chinese Americans. His papers are the source for the recently opened exhibition "Y.C. Hong: Advocate for Chinese-American Inclusion,"on view in the West Hall of the Library from Nov. 21, 2015 to March 21, 2016.

One way to get around the Exclusion Act was to prove you were the son of a Chinese American. An important service offered by immigration lawyers like Hong was helping applicants prepare for an arduous interview process. Applicants could be asked hundreds of questions, and their answers were compared to those of their relatives to assess whether they were telling the truth. Hong’s archive contains poignant examples of this process.

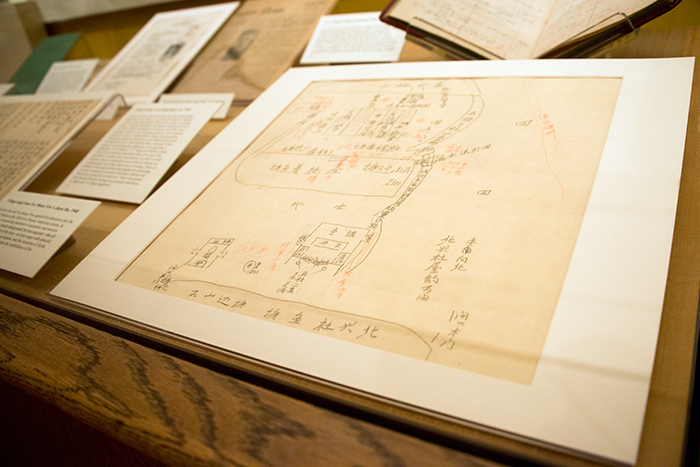

In one of the exhibition's display cases is a map produced by a 12-year-old boy showing a sketch of his home village in China. Immigration officials had the boy draw an annotated map and then used it to test relatives on who lived in each house. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A map produced by a 12-year-old boy shows a sketch of his home village in China. Immigration officials had the boy draw an annotated map and then used it to test relatives on who lived in each house, as well as on the locations of a fish pond, several farms, and surrounding mountains. Another object, a long Chinese calligraphy scroll, contains the questions and answers an applicant could use to prepare for the interview—a so-called “coaching paper.”

Organizing the exhibition has had a personal effect on Li Wei Yang, The Huntington’s curator of Western American History. A first generation immigrant himself, Yang says he had originally thought of his own immigration experience as difficult. That changed as a result of this show. “My immigration experience was really nothing compared to what people had to go through back then,” he says.

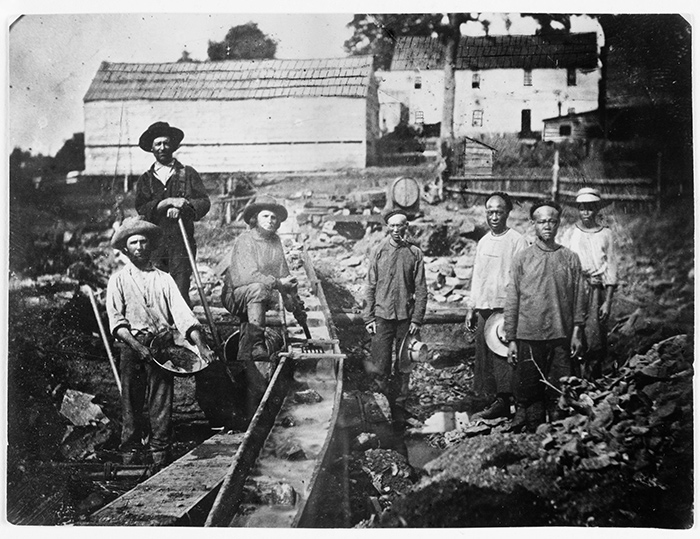

Chinese miners at the head of the Auburn Ravine, ca. 1852. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Chinese immigrants, mostly from southern China, started pouring into the U.S. in the 19th century to fill a labor shortage. Photos of Chinese laborers working in mines and building railroads launch the exhibition, along with news clippings documenting fears about their growing numbers, which then led to severe restrictions.

Hong was born in San Francisco, graduated from Berkeley High School, and earned degrees from the University of Southern California. He was acutely aware of the Exclusion Act, the subject of his Master of Laws thesis, which is also on display.

His career as a lawyer bridged several phases of U.S. immigration policy. The Exclusion Act was in effect when he became a lawyer in 1923. He was still practicing law at the time of a major reform, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which shifted the focus from national quotas to an examination of an applicant’s skills and their family relationships with citizens or U.S. residents.

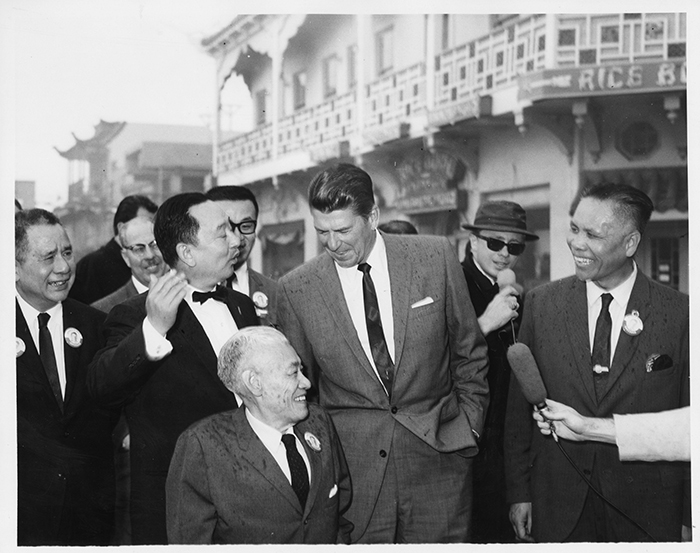

Y.C. Hong and Governor Ronald Reagan, late 1960s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The legendary attorney testified at hearings in Washington, D.C. (you can view his positions on proposed laws sketched out on yellow pads on display) and lobbied and befriended important politicians, such as California congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas and California governor Ronald Reagan.

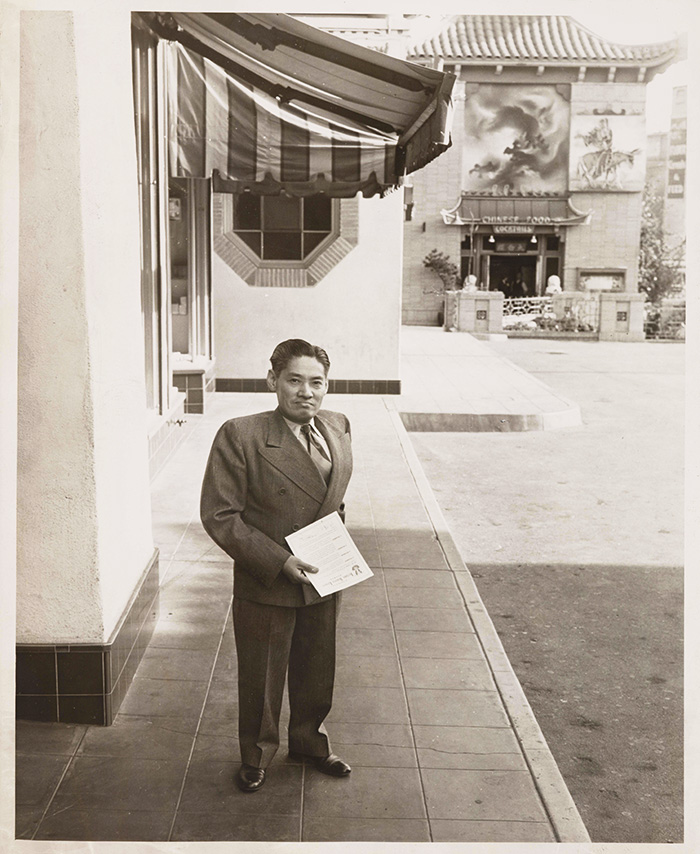

Hong worked on at least 7,000 immigration cases during his career, but his vision of the Chinese in America went beyond legal matters. Los Angeles’s New Chinatown, which he helped build, is an expression of inclusion. The old Chinatown, which was replaced by Union Station, had been an area known for opium, prostitution, and gambling. In the 1930s, Hong and other prominent Chinese Americans launched the first planned Chinatown in North America, evoked in the exhibition by large color photographs and other memorabilia.

Says Yang, “The New Chinatown became a place where people could take their families and enjoy Chinese food, as well as learn about Chinese culture. The founders of the New Chinatown—Peter SooHoo and others, including Hong—wanted it to be not only for the Chinese, but also for all visitors.”

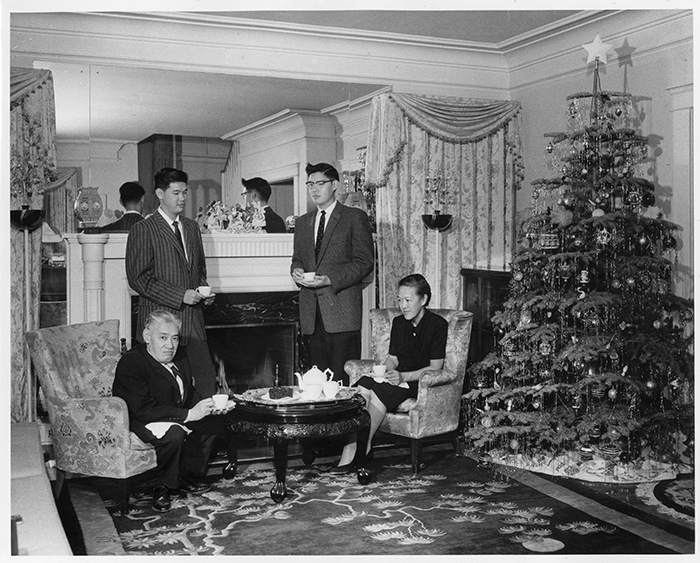

Christmas portrait of the Hong family, ca. 1960s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Hong moved his law offices to New Chinatown, where you can still find the Hong Building, located on the west side of Broadway near a gate that Hong built in honor of his mother.

This exhibition is the first opportunity for the public to learn about Hong through the You Chung Hong Family Papers, acquired by The Huntington in 2006, as a gift from Hong’s younger son, the late architect Roger Hong. (His surviving elder son, Nowland Hong, is a lawyer practicing in Los Angeles.)

“The Chinese immigrant experience is not something you learn about in a general school curriculum,” says Yang. “I’d heard about exclusion growing up, but curating the exhibition has been truly eye opening.”

Y.C. Hong in New Chinatown, 1950s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can read an article about this exhibition in the Los Angeles Times and watch a video about it (in Chinese and English) on the Phoenix TV website.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles-based communications consultant.