The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

CONFERENCES | Finding a New Place for the Frontier Thesis

Posted on Thu., Feb. 16, 2012 by

Erik Altenbernd and Alex Young are just now completing their graduate coursework at UC Irvine and USC, respectively. They both study California and the American West, Altenbernd as a historian and Young as a literary scholar. Before diving into their dissertations they have been pondering the granddaddy thesis of them all—Frederick Jackson Turner's famous (and infamous) essay from 1893, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History."

Turner (1861–932) was the premier scholar of Western history of his generation. In 1893, when the American Historical Association held its annual meeting in conjunction with the Chicago World's Fair, Turner delivered the so-called Frontier Thesis, which has been a point of contention in one form or another for every generation of scholars that has followed. In it Turner proposed that American society owed its distinctive character to its constant push westward across what he called an "undeveloped frontier."

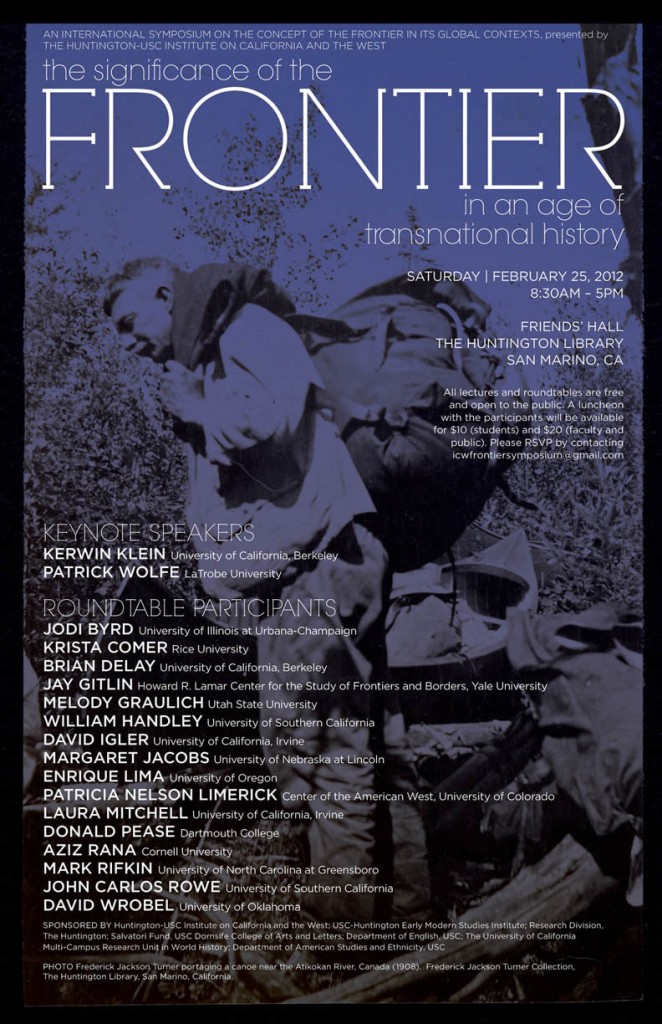

Altenbernd and Young have organized a symposium called "The Significance of the Frontier in an Age of Transnational History," which will take place Sat., Feb. 25, in The Huntington's Friends' Hall. "We're bringing together a group of scholars from various fields to explore new ways to conceptualize the frontier," says Altenbernd. "By expanding the conversation across disciplines and regions—Australia, Asia, Africa, and Latin America, included—we hope to create a worthwhile conversation about frontiers, in the plural."

Among the panelists will be Patricia Limerick, a well-known critic of the so-called Frontier Thesis who came of age as a scholar about 25 years ago with what became known as the New Western History. Altenbernd and Young have devised three panels that will tackle the idea of the frontier from the perspectives of history, literature, and the burgeoning field of settler colonial studies.

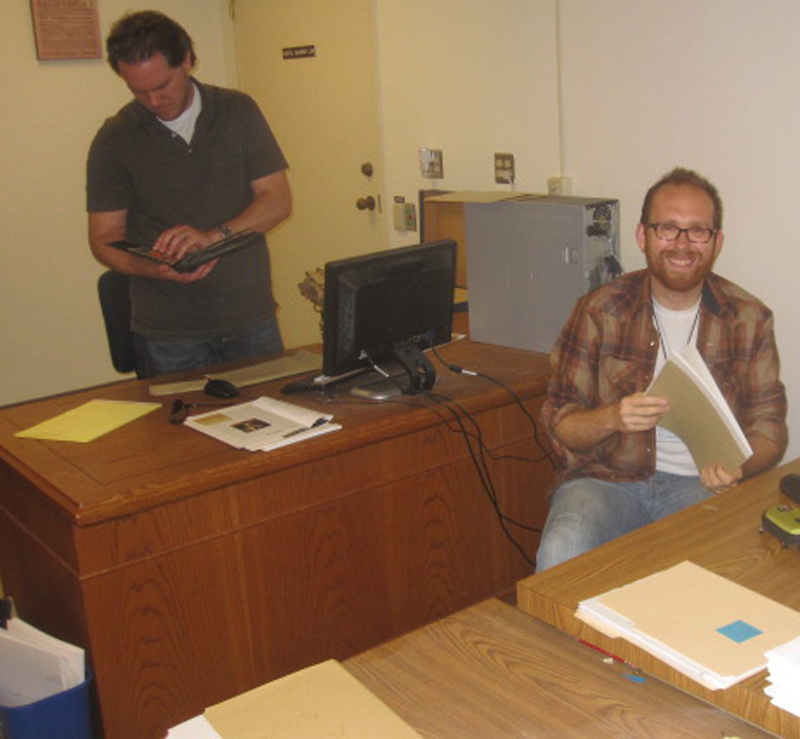

Erik Altenbernd (standing and holding a Turner family photo album) and Alex Young at work last year at The Huntington with the Turner papers.

The pair's inspiration for the conference goes back a year or so to their Huntington internships helping to catalog a backlog of manuscript collections related to California history. A three-year grant from the Mellon Foundation brought in graduate students like them with a vested interest in creating accurate and meticulous finding aids, or inventories, of collections. Among their assignments was to fill a gap in the description of the papers of The Huntington's first research associate, the very same Frederick Jackson Turner. He had been wooed west in 1924 by Max Farrand, the Huntington's first director, after his notable tenures on the history faculties of the University of Wisconsin and Harvard.

During their internship, Altenbernd and Young were also enrolled in a Western history seminar taught by William Deverell, professor of history at USC and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. (The USC graduate course convened at The Huntington each week and welcomed students from UCLA, UC Riverside, and UC Irvine.)

With Deverell's encouragement, a symposium began taking shape. "Having Alex and Erik propose, much less organize and execute, such a broad-gauged conceptual project as a reconsideration of the frontier by way of very recent scholarship, is really pretty extraordinary," says Deverell. "I can't commend the two of them highly enough. They thought this thing up, they worked hard to make it happen, and they've gained invaluable experience as to how scholarly curiosity can be supported and furthered through deliberate, careful planning of ambitious events."

For more details on the symposium, including registration details, visit the website of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.