The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Conserving a Classic Book on Sunspots

Posted on Fri., May 22, 2015 by

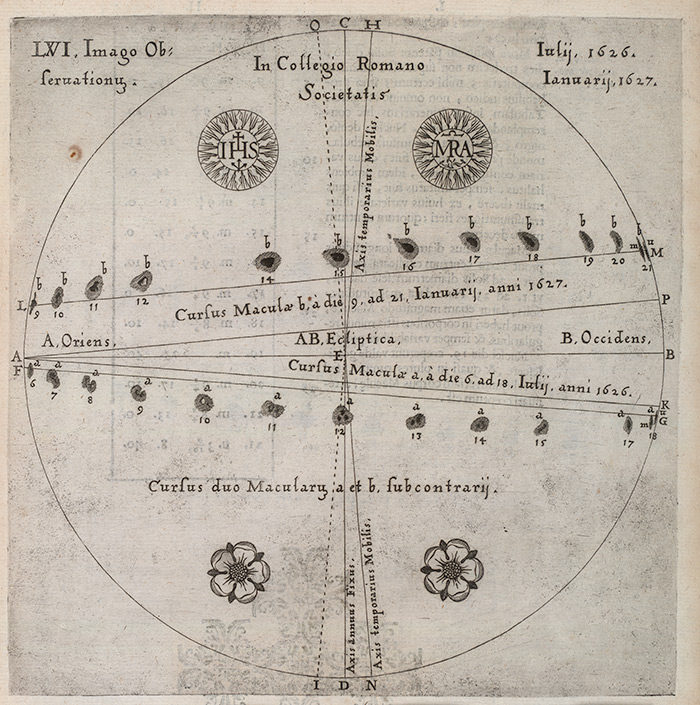

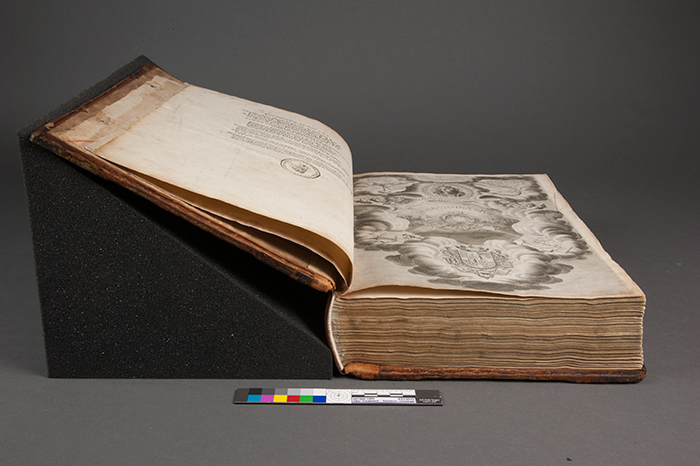

Depiction of sunspots in Rosa Ursina sive Sol, an illustrated astronomical text published by Christoph Scheiner in 1626. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On my last day as the Dibner Conservator for the History of Science collection at The Huntington, I want to share one of the more interesting and complex conservation treatments I’ve completed here—rebinding George Ellery Hale’s copy of Rosa Ursina sive Sol. Christoph Scheiner, a German Jesuit renowned for his studies of sunspots, published this beautifully illustrated astronomical text in 1626. It remained the standard text on sunspots for a century after its publication.

George Ellery Hale (1868-1938), the founder of the Mount Wilson Observatory, was a solar physicist who made the discovery that sunspots have magnetic fields. He donated his copy of Rosa Ursina to the Mount Wilson Observatory library before it came to reside at The Huntington, along with the rest of the Mount Wilson collection.

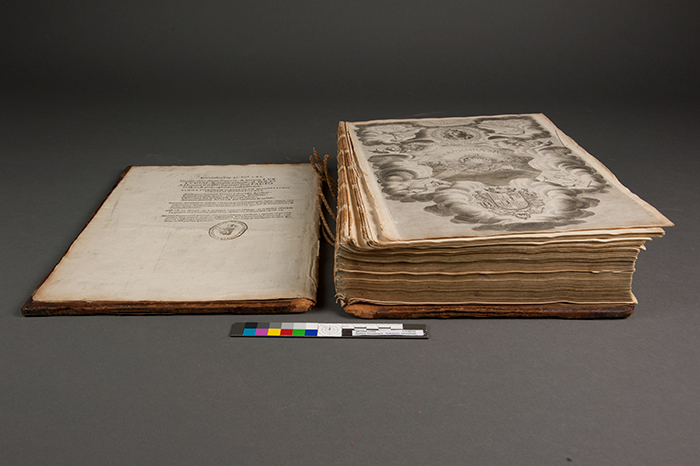

Rosa Ursina, completely disbound. Many beautiful engravings appear throughout the book, often incorporating imagery of bears, a reference to the book’s patron, Paolo Jordano Orsini, Duke of Bracciano. Orsini is an Italianized form of the Latin word for “bear.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Hale’s copy of Rosa Ursina was originally bound in brown calf over wooden boards, with ornate blind stamping on the boards’ faces. When the book first came to the conservation lab, it was completely disbound, making it impossible to handle safely. Many Huntington scholars had requested Rosa Ursina over the years, but they were unable to access it in its disbound condition.

The first step I took was to reinforce each gathering—a set of conjoint leaves—by adhering a thin strip of Japanese tissue along the fold. This gave the fold increased strength and ensured that the gatherings would be able to support the tension of the thread when I resewed the volume. The text block is more than four inches thick, and sewing it took a long time. I also mended tears on the first and last pages of the text block and filled gaps around the perimeter of the frontispiece.

I adhered a thin strip of Japanese tissue to the spine fold of each gathering. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Then I turned to the supports that held the text block together. The lower wooden board had somehow managed to retain most of the original sewing supports—thick pairs of linen cords around which the sewing threads were wrapped to provide the mechanical consolidation of the text block. As I worked to sew the gatherings back to the binding, I needed to incorporate this original material and also find a way to give the book an additional means of support.

I ended up threading thin, soft linen bands behind each of the original sewing supports so that, as the binding flexes, the new threads bear most of the tension. However, several cords were missing entirely. A colleague at The Huntington taught me how to cable new cords using linen thread and a cordless drill. You extend four strands of two-ply thread across the length of a very large room, with one person on one side of the room holding the strands taut, and another person on the other side of the room holding an electric drill and a hook attachment. You attach the thread to the hook, and as the drill rotates, the cord twists into a tight cable. Then you hold the cord to maintain the tautness as the cord folds over onto itself and finally rotate the drill in the opposite direction.

When done correctly, the thread locks into place and resists unraveling due to the opposing twist of the original thread. I was gratified to see that the cords were almost identical in diameter and density to the original ones. I frayed out the ends of these new cords and adhered them to the board behind the stubs of the originals.

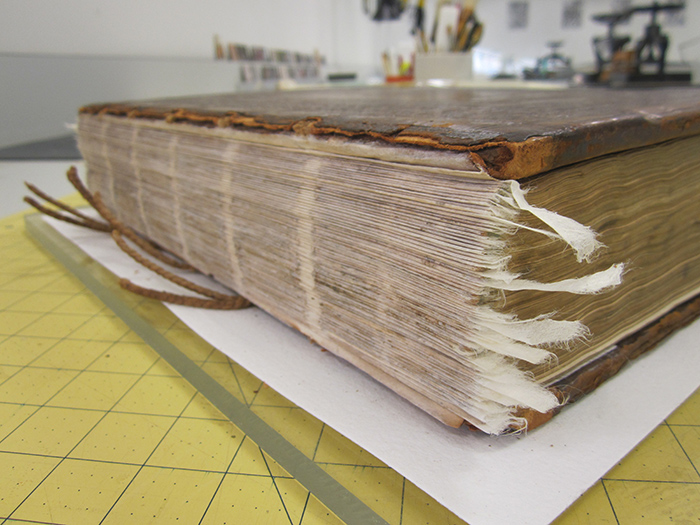

The resewn text block incorporates both the original sewing supports and the newly cabled cord. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Then I needed to sew the text block directly onto the boards. (Traditionally, a text block is sewn independently of the boards, which are then laced on at a later stage. But in this case, the first and last gatherings were still attached to the boards, and the sewing supports were still attached to the lower board.) So I set up the lower board on a sewing frame, tensioned the new cords and support threads, and began sewing. In rare book conservation, it’s unusual to have the opportunity to completely resew a text block, and this became my favorite part of the treatment. It took several days of methodical sewing and careful tensioning to complete this step.

After I closely examined the upper board, I realized that there was a small split in the wood. I mended the split by using a small brush to insert leaf gelatin—a natural, collagen-based adhesive—and clamped it overnight. Once I stabilized the board, I also sewed it on, and removed the book from the sewing frame. I then lined the spine panels with Japanese tissue and aeroplane linen—a very fine and tightly woven material originally used to cover the wings of airplanes. These linings extended onto the board edges to provide an additional method of board attachment. I also sewed new silk endbands over linen cords and adhered them to the head and tail of the textblock.

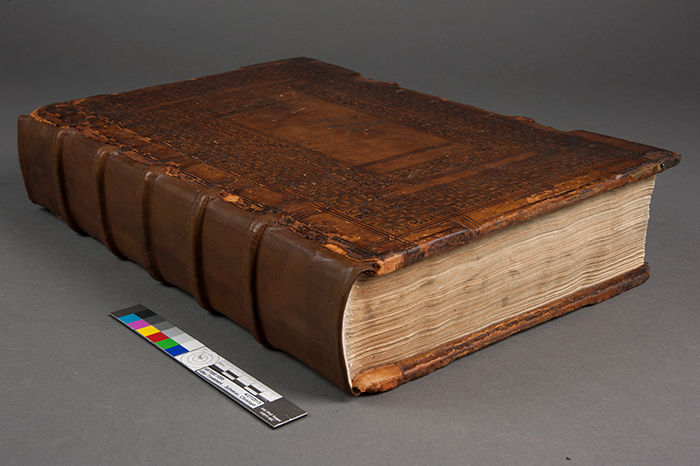

I used a new piece of toned calf leather to reback the text block, inserting the new leather directly beneath the existing leather. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The final step of the treatment was rebacking the book with new leather. Rebacking entails covering the spine of a book with new material—often leather or toned Japanese tissue—when the original spine material is either missing or badly abraded. I pared undyed calf leather to a suitable thickness and toned it to approximate the mottled dark brown leather on the boards. The book had already been rebacked at some point in its history—likely in the 18th century. I wanted to maintain the evidence of this earlier restoration, so I inserted the new leather beneath both layers of existing leather.

The book now opens smoothly and can be handled safely by researchers. I feel very fortunate to have worked on such an important, complex, and engaging conservation treatment.

Huntington researchers can now safely consult the rebound book. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Today is Jennifer Evers' last day as the Dibner Conservator for the History of Science collection at The Huntington. She will be joining the conservation staff at the Library of Congress.