The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

David Armitage, Francis Lieber, and Civil Wars

Posted on Wed., March 14, 2018 by

Francis Lieber (1815–1888) authored General Orders No. 100 for the Union army in 1863—in the midst of the U.S. Civil War. The work codified the laws of war for the first time and prefigured the Geneva and Hague conventions. The military still references the “Lieber Code.” This engraving of Lieber, by H.B. Hall & Sons of New York City, appears in The Supreme Court of the United States: its history, 1901, by Hampton L. Carson. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The concept for the book Civil Wars: A History in Ideas, David Armitage’s examination of bloody conflicts from ancient times to the present, germinated in the idyllic surroundings of The Huntington. When the author revisited The Huntington more than a decade later to deliver the Crotty Lecture last month, he recounted the coincidence that led him to a topic he never expected to investigate.

“You could say the subject found me,” said Armitage, the Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History at Harvard University.

In 2006–7, Armitage was a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at The Huntington. The Second Gulf War raged. Between October 2006 and January 2007, an average of 3,000 people a month—including soldiers, civilians, Iraqis, and invaders—were dying in Iraq.

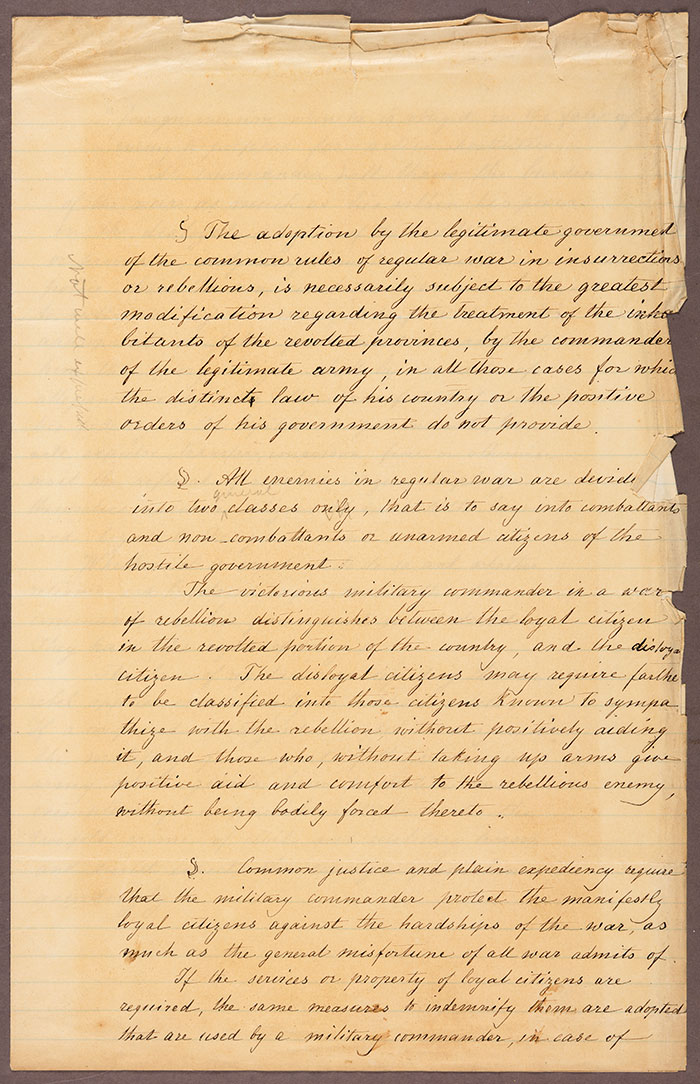

Manuscript from the drafts of the Lieber Code. The first sentence reads: “The adoption by the legitimate government of the common rules of regular war in insurrections or rebellions, is necessarily subject to the greatest modification regarding the treatment of the inhabitants of the revolted provinces, by the commander of the legitimate army, in all those cases for which the distinct law of his country or the positive orders of his government do not provide.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

At the same moment, Armitage discovered The Huntington’s Francis Lieber papers, a collection of roughly 6,000 items, including notes, correspondence, manuscripts, and printed materials. Francis Lieber (1815–1888) authored General Orders No. 100 for the Union army in 1863—in the midst of the U.S. Civil War. The work codified the laws of war for the first time and prefigured the Geneva and Hague conventions. The military still references the “Lieber Code,” as it’s commonly known.

Lieber, a lawyer and professor of political science, was uniquely qualified for the challenge. Prussian by birth, he immigrated to the United States, where he taught first at the University of South Carolina and then at Columbia College (now Columbia University) in New York City. He had three sons, two of whom fought for the Union, one for the Confederacy. In May 1861, Lieber wrote, after the death of one of his sons in battle, “Behold in me the symbol of civil war.”

As Armitage read through Lieber’s letters, he experienced Lieber’s grappling with issues such as the status of enemy combatants, the treatment of prisoners taken on the battlefield, and the rules of military justice. The mid-19th-century correspondence resonated with daily headlines about the George W. Bush administration’s “Global War on Terror.”

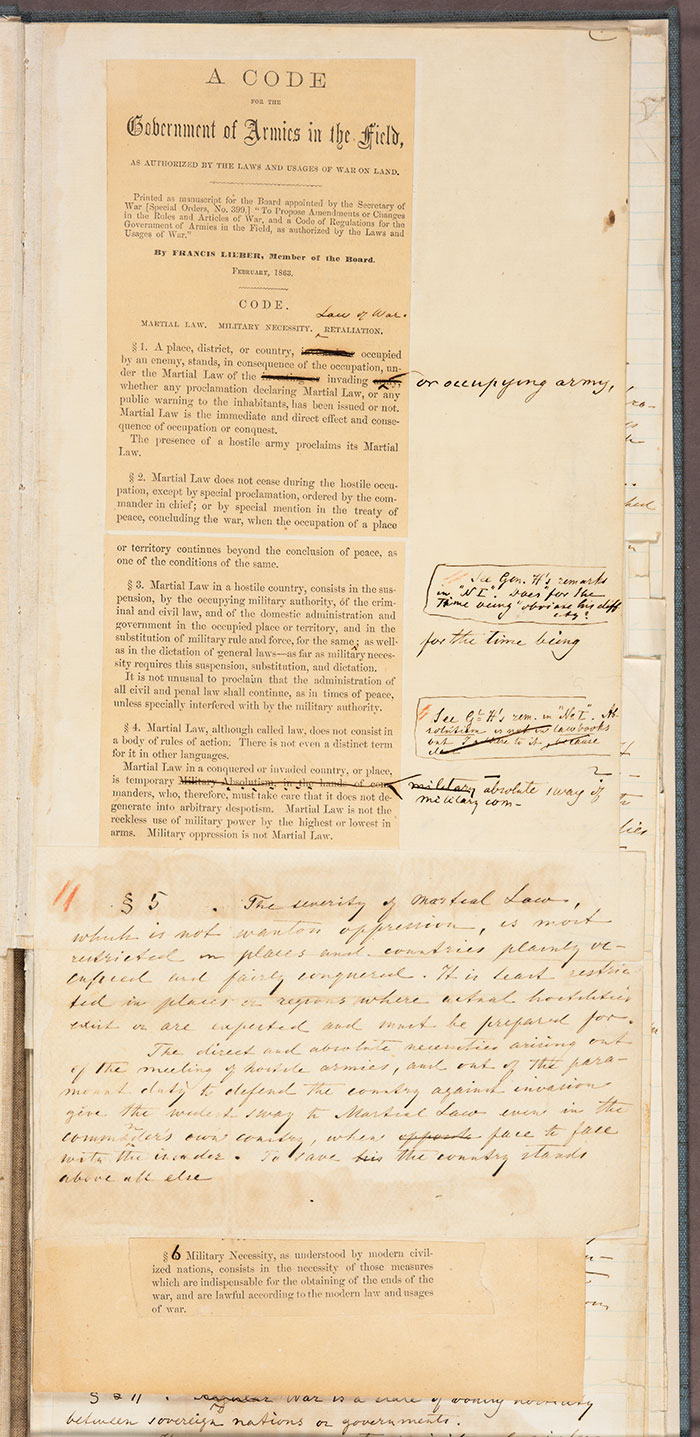

Annotated draft of the Lieber Code. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“I found the past rhyming with the present,” said Armitage. In 2006, media, commentators, and the administration pondered what to call the Iraq War. The Los Angeles Times and some other major dailies called it a civil war. The administration and voices on the right objected. Lieber had been equally perplexed about what to call the war in which his sons fought.

He found it difficult to distinguish among the terms “civil war,” “rebellion,” “insurrection,” and “invasion.” A draft of the code that Lieber sent to Henry Wager Halleck (1815–1872), the international lawyer and Union general who had commissioned Lieber’s work, avoided defining civil war. Halleck wrote, “To be more useful at the present time it should embrace civil war as well as war between states or distinct sovereignties.” In March 1863, Lieber replied, “I am writing my 4 sections on civil war and ‘invasion.’ Ticklish work, that.”

Armitage came to view 1863 and 2006 as but two stops along a long journey that starts in the Republic of Rome and extends to the present day. He noted that, in 2016, there were some 50 armed conflicts around the globe—all but two of them within a single country. Civil wars were the most destructive of these. Economists estimate the human, material, and economic cost of such civil wars at $123 billion per year.

Annotated photostat of the Lieber Code. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Armitage believes the historian should not attempt to define civil war—“definitions never satisfy everyone”—but to excavate the conflicts. Civil Wars, recently released in paperback, provides perspective on the roots and dynamics of civil war and its shaping force in today’s world.

Armitage concluded his Crotty Lecture with “tempered hope” for the future. “What humanity has invented,” he said, “they can uninvent.”

You can listen to David Armitage’s Crotty Lecture, “Civil War: A History in Ideas,” on SoundCloud.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.