The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Dazzling in the Midst of War

Posted on Fri., July 31, 2015 by and

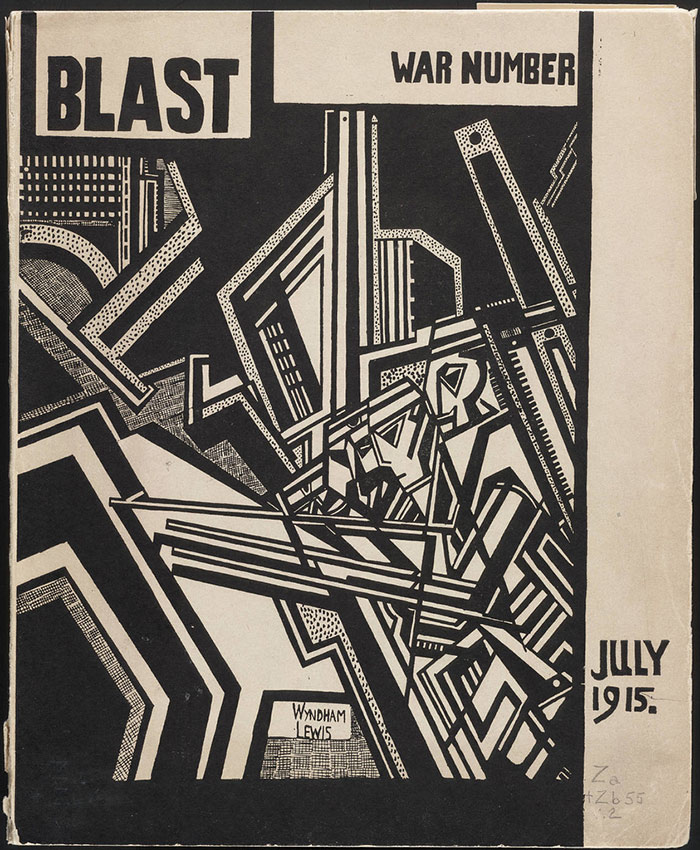

Cover for the second issue of Blast, 1915, designed by Wyndham Lewis (British, 1879–1939), woodcut. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, and New York: John Lane Company, 1914–1915. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

What do avant-garde art and Britain’s Royal Navy have in common? The answer is Edward Wadsworth (1889–1949), a British artist whose work is currently part of The Huntington’s “Between Modernism and Tradition: British Works on Paper, 1914–1948” exhibition, on view in the Huntington Art Gallery through Sept. 21, 2015.

Wadsworth was one of the original members of the Vorticist group, a short-lived, avant-garde artistic and literary movement inspired by Cubism and Futurism. The English painter Wyndham Lewis and the American poet Ezra Pound, who published the magazine Blast as a platform for their ideas, founded Vorticism. As an artistic style, Vorticism was known for jarring colors and assertive lines as well as an embrace of modernity and the machine age. The second issue of the magazine, on view in the exhibition, has a cover designed by Lewis, depicting armed men moving as if mechanized through a tangled geometric cityscape.

Wadsworth was a signatory of the Vorticist manifesto published in Blast and contributed to the content of the magazine. His image of Street Singersfrom 1914, on display in the exhibition, clearly reveals the artist’s sympathy with Vorticism, especially in its interest in the machine. Without the drawing’s title, it would be possible to mistake these human forms for the metal gears and bolts of some great mechanical apparatus.

Edward Wadsworth (British, 1889–1949), Street Singers, ca. 1914, ink on wove paper. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Only 33 days after the publication of the first issue of Blast, England declared war on Germany. Wadsworth signed up for the navy in 1915, shortly after the second and final issue came out. Fellow Vorticist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska had already been killed at the front. Wadsworth, however, was sent to the Greek island of Lemnos, where the Allies had a base at Mudros. There, it was Wadsworth’s skills as an artist, rather than his skills as a sailor, that were called upon in the service of his country.

Wadsworth spent the war transferring camouflage patterns onto the hulls of ships. This camouflage, however, didn't employ the typical muted tones designed to conceal ordnance from the enemy by blending in with the environment. Wadsworth painted camouflage patterns that consisted of graphic lines and shapes in bold colors—black, blue, green, and even neon red.

Called “dazzle” (or “razzle dazzle”) camouflage, these painted designs were not intended to conceal the ships they covered. Rather, dazzle camouflage worked to confuse and disorient the enemy. Developed by the English painter Norman Wilkinson and based on the ideas of the Scottish zoologist John Graham Kerr, the complex patterns, made up of disrupting lines and contrasting colors, were intended to prevent the enemy from gauging a vessel’s speed, size, and direction. Kerr compared dazzle’s irregular outlines and contrasting shades to the coloring of a giraffe, zebra, or jaguar, which “looks extraordinarily conspicuous in a museum but in nature, especially when moving, is wonderfully difficult to pick up.”

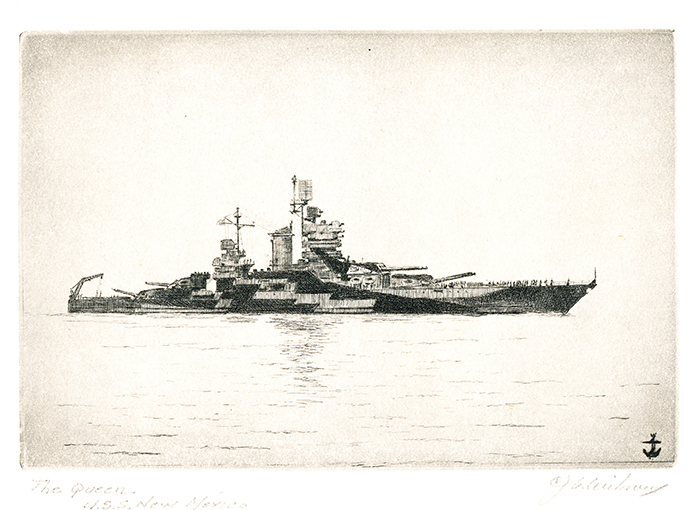

Starboard view of the USS New Mexico (BB-40), approximately 1944, at sea, painted in dazzle camouflage. The Queen: U.S.S. New Mexico, by Charles J.A. Wilson (1880–1965), drypoint, no date, John Haskell Kemble Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The practical success of dazzle camouflage is a matter of debate, though it continued to be used through World War II. (The Huntington Library’s Kemble Collection includes an image of a United States dazzle ship from World War II.) Wadsworth’s own experiences with dazzle ships had a lasting effect on his later art, which became more figurative, less abstract. Though he often turned to nautical themes, he, like many of his fellow avant-garde artists, moved away from the Vorticist belief in the positive power of the machine. Indeed, it was the devastating destruction of mechanized warfare witnessed by artists such as Wadsworth during World War I that brought an end to artistic movements such as Vorticism and profoundly changed the paths of many careers.

You can see more images of dazzle ships at The Public Domain Review.

Related content on Verso:

Lusitania’s Anchor to the Past (May 7, 2015)

Katherine Christiansen is an intern in the art division at The Huntington.

Melinda McCurdy is associate curator of British art at The Huntington.