The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Deliberate Omissions

Posted on Wed., Nov. 8, 2017 by

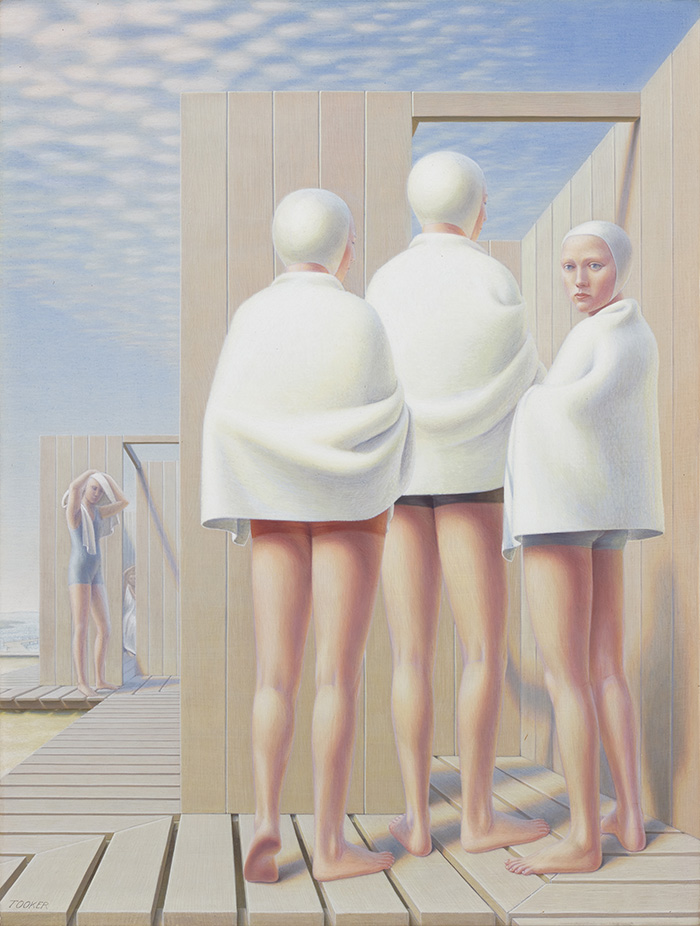

George Tooker (1920–2011), Bathers (Bath Houses), 1950, egg tempera on gessoed board, 20 3/8 x 15 3/8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of George Tooker, Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Often when we view a painting, we take stock of the storytelling elements that leave us with a certain thought or feeling. Especially when we are confronted with works that are associated with realism, we expect a painted scene to make sense. But how do we understand works that seem to purposely leave out key elements of the story? When we’re left wondering, “What am I missing here?”

The American artists George Tooker (1920–2011) and Edward Hopper (1882–1967) are known for works that evoke a sense of isolation.

While it isn’t essential to know the backstory of an artist to create opinions of their works, knowing how their oeuvre has been categorized can give us some context. Hopper attended the New York School of Art and Design and studied under Robert Henri. He is often associated with his peers in the Ashcan school, and yet his vacant, lugubrious scenes don’t quite fit in with the gritty portrayals of lower-class modern life that are typical of those artists. Tooker is associated with the artistic genre of magic realism, in which scenes portrayed are primarily realistic but also incorporate magical elements.

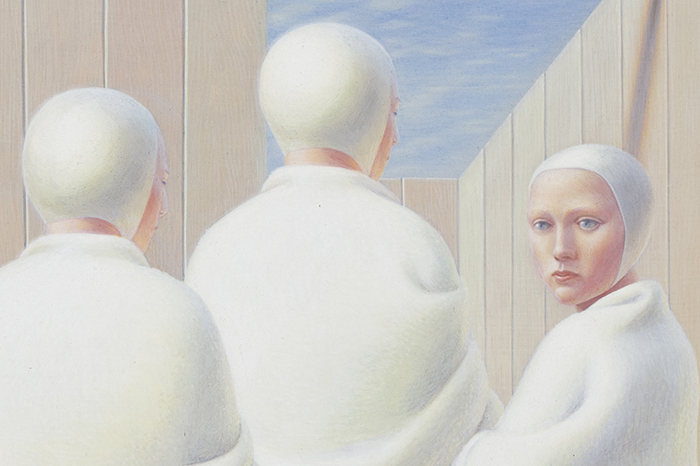

There is something unsettling about the glassy look in the eye of the figure on the right. George Tooker (1920–2011), detail from Bathers (Bath Houses), 1950, egg tempera on gessoed board. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of George Tooker, Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Both Tooker’s Bathers (Bath House) (1950) and Hopper’s The Long Leg (1930) depict sunny days and use a soothing color palette of pastel blues and crisp whites. At first glance, their subjects seem pleasant enough—in Tooker’s case, a group of people bathing, and in Hopper’s work, a sailboat on the water. Yet there is something unsettling about the glassy look in the eye of the figure on the right in Bathers and the eerie stillness of The Long Leg, as though something is missing from the implied narratives of each that prevents us from fully understanding what is going on.

In Bathers, we see a group of people at a bathhouse. The periwinkle sky is dappled with clouds, and both the bathers and the bathhouse appear clean and pristine. Three figures in the foreground wait to enter the bathhouse, each with a bright white bathing cap and a crisp white towel around their shoulders. One of the bathers in the foreground and another in the background, drying hair, seem to be staring at viewers, as if we are interlopers in this space. An additional figure, who we can see only as a sliver inside the bathhouse, also seems to be investigating us. This interaction with viewers engages us and invites us to be a part of the composition.

A figure that can be seen only as a sliver inside the bathhouse seems to be investigating viewers. George Tooker (1920–2011), detail from Bathers (Bath Houses), 1950, egg tempera on gessoed board. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of George Tooker, Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Upon close inspection, when one is just feet from the painting, it’s no longer clear if the gazes of these figures are staring at viewers. The frontal figure’s eyes seem glazed over, glassy and reflective. The figure drying hair turns fully toward us, and yet the eyes are cast downward. Taking into account all of these observations, it’s still not clear what’s happening. We’re left questioning why these bathers all look so similar, why the foremost figure gives such a haunting stare, and why the artist has made us feel so strange about viewing what could have been an unassuming scene of swimmers showering off.

Edward Hopper (1882–1967), The Long Leg, ca. 1930, oil on canvas, 20 x 30 1/4 in. (50.8 x 76.8 cm.). Gift of the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Like Tooker’s piece, Edward Hopper’s The Long Leg depicts a serene, sunny day. While the painting is named for the movement of the boat, tacking back and forth into the wind, the water appears calm, and the boat hardly disturbs the water. Furthermore, why isn’t anybody enjoying the fine weather, not even on the boat itself? While we might expect to see sunbathers on an open, sandy beach, we could postulate reasons for why they are missing. Perhaps the beach is closed or it’s an early fall day when most beachgoers have already gone home. But the absence of a pilot on the boat is more difficult to justify. In what is otherwise a simple seascape, we are confronted with missing elements that necessitate a consideration of the work as being more than a representation of the literal world.

These missing elements are as integral to our overall impression as the elements the artists choose to portray. While we are able to identify characteristics that are discordant with what we expect to see in a painting, we still do not have access to a complete narrative to explain why unusual elements have been included. Could Bathers be pointing to the emptiness of a world where people must “fit in” and subscribe to the status quo? Or perhaps the viewer is imagined as the spitting image of a dear friend who has just passed away—the vacant stares and averted eyes hardly concealing their dredged-up sorrow.

No one can be seen enjoying the fine weather, not even on the boat itself. Edward Hopper (1882–1967), detail from The Long Leg, ca. 1930, oil on canvas. Gift of the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

What if The Long Leg is the image of a place where humans no longer exist, but their creations keep performing their intended purposes?

Or maybe it’s none of these things. You may prefer to conclude that the missing pieces of these narratives are meant to leave you feeling perturbed, and the fact that you may walk away from these works with their stories unresolved is what gives them their emotional power.

While we may not find obvious answers to what’s going on in these scenes, the unanswered questions encourage a discourse between the painters and viewers. Leaving the stories incomplete invites visitors to fill in the blanks or at least ponder the meaning of the questions.

Perhaps the beach is closed or it’s an early fall day when most beachgoers have already gone home. Edward Hopper (1882–1967), detail from The Long Leg, ca. 1930, oil on canvas. Gift of the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Molly Curtis is pursuing her master’s degree in art history at UC Irvine and has served as an intern in the American art department of The Huntington Art Collections.