The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Down to Earth

Posted on Tue., Aug. 28, 2012 by

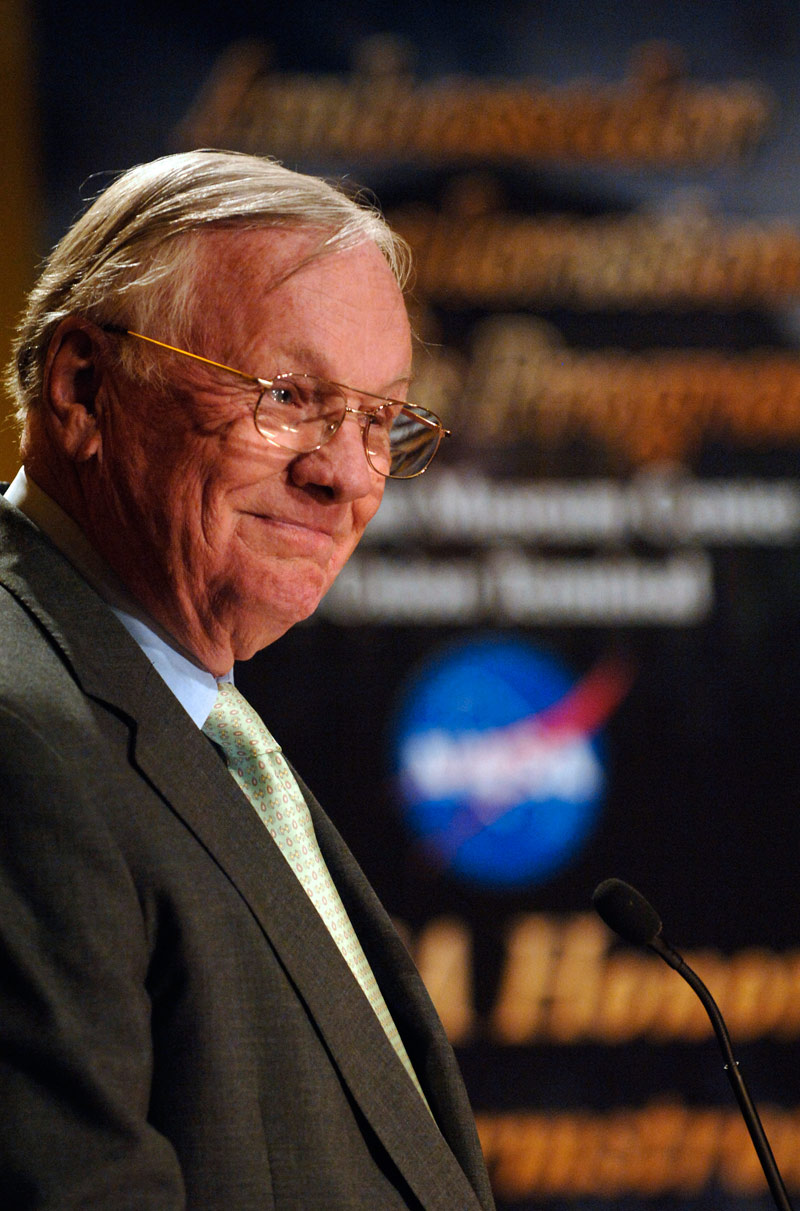

Neil Armstrong accepts NASA’s Ambassador of Exploration Award at the Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal, in April 2006. Photo credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls.

Neil Armstrong, who died Saturday at the age of 82, was a member of a select group—astronauts who walked on the moon. And as the first man, he occupied an even higher stratosphere, keeping company today in the public consciousness with Sally Ride, the first American woman to fly into space, who passed away last month at the age of 61.

Armstrong famously eschewed the limelight. In looking back on his career, he liked to identify himself with the engineers whose work helped ensure his safe passage. He knew that before he took that famous first step, he had to land the Eagle lunar module safely on the moon.

“I am, and ever will be, a white socks, pocket protector, nerdy engineer,” Armstrong said in 2000, as quoted in many obituaries this past weekend. “And I take a substantial amount of pride in the accomplishments of my profession.”

During the run of the 2011 Huntington exhibition “Blue Sky Metropolis: The Aerospace Century in Southern California,” co-curator Peter Westwick described the male-dominated world of aerospace culture and its competing stereotypes of the maverick test pilots made famous by Tom Wolfe and the nerds with horn-rimmed glasses and pocket protectors who labored anonymously in far greater numbers behind the scenes. Armstrong had a rightful place in both camps, having studied aerospace engineering at Purdue University before joining the Navy and flying 78 missions during the Korean War. (He would later earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at USC.)

As early as the 1950s, when Armstrong arrived at Edwards Air Force Base, he did not fit cleanly into either of those prevailing aerospace myths. “Armstrong, perhaps more than any other individual of the era, represented the kind of college-trained, academically minded engineer-pilot NASA wanted for its astronaut program,” says Matthew Hersch, co-curator of the exhibition “Blue Sky Metropolis” and author of the forthcoming book Inventing the American Astronaut. “While older test pilots at Edwards Air Force Base prided themselves on their intuitive command of their craft, Armstrong was a diligent bookworm other pilots regarded as a bit of a nerd, an identity he wore as a badge of honor.”

Hersch, who spent the 2010–11 academic year as a USC-Huntington postdoctoral research fellow, is now a lecturer in the department of history and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. In an e-mail message to me on Sunday, he elaborated on this aspect of Armstrong’s legacy:

Armstrong so distinguished himself as a civilian test pilot for the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA, NASA's predecessor) that in June 1958, he was secretly named as a candidate for the Air Force’s Man-In-Space Soonest project, the nation's first space program. This project never panned out, but Armstrong was critically involved in other spaceflight efforts (including the X-15 and X-20) before joining the NASA astronaut corps in 1962.

Stable and studious, he was a bit of mystery to many who worked with or near him, including Norman Mailer. Mailer’s profile of Armstrong in his 1970 book Of a Fire on the Moon described Armstrong as emotionless and inscrutable. During a 1966 Gemini mission and a 1968 test of a lunar landing simulator, Armstrong skillfully recovered from flight mishaps with only seconds to spare. Even more odd, he responded to both incidents as if virtually nothing had happened. An hour after ejecting from the lunar landing trainer, he was back at his desk working, a kind of “cool” that shocked even fellow astronauts.

Armstrong’s ability to stay calm and focused under pressure would serve him well during the moon landing, when he brought the Eagle down on the lunar surface with less than 30 seconds of fuel to spare. Perhaps, during those historic final moments before touchdown, Armstrong would not have seen much of a distinction between operating the controls of a spacecraft and solving a complex problem at an engineer’s desk.

Armstrong and the X-15 at the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, Jan. 1, 1960. Photo credit: NASA.

Hersch’s book, Inventing the American Astronaut, will be published by Palgrave Macmillan in October 2012; Westwick is editor of Blue Sky Metropolis: The Aerospace Century in Southern California, co-published by the Huntington Library Press and the University of California Press earlier this year. He is director of the Aerospace History Project, an initiative of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.