The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Elves and the HDLmaker

Posted on Fri., June 15, 2012 by

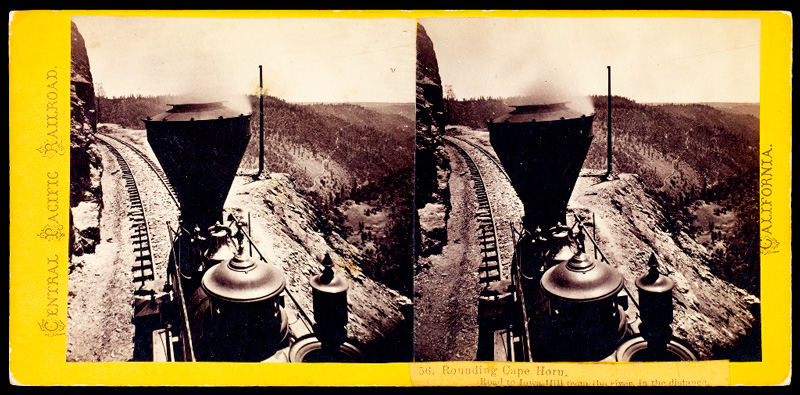

The current exhibition "Visions of Empire: The Quest for a Railroad Across America, 1840–1880" tells the story of the extraordinary achievement and implications of the first transcontinental railroad. In the 1860s, photographer Alfred A. Hart followed the progress of workers as they punched the Central Pacific Railroad through the Sierras. These photographs became the basis for a set of stereo cards; two seemingly identical images on each card are combined in the brain when placed into a stereoviewer, giving the perception of three-dimensional depth. In the exhibition some 300 of the available 337 Hart stereo cards from The Huntington are mounted on the wall of the education room. It is an awe-inspiring sight.

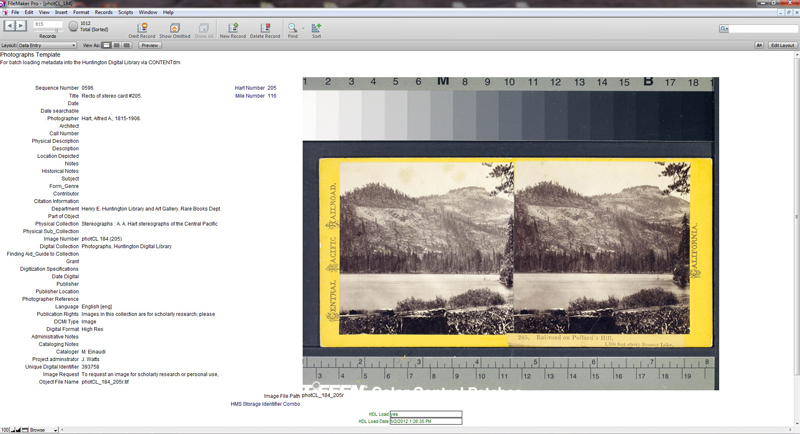

Now all 337 Hart stereo cards, images once available to researchers only, are also available to everyone online, recently added to the Huntington Digital Library (HDL). But rarely will researchers, or even the general public, wonder about how the digital images got online in the first place. They will view the images, possibly use one of them for a slide show, and then move on. Do people ever stop to think about metadata? That is the specific information that makes an item unique and findable: title, date, photographer, brief description, department, and collection. In the past, they might have found such information in a card catalog; today it is online, often in the background and invisible. And if they do stop to think about the data, will they also wonder about the people who supplied the data? For all they know, the metadata just magically appeared as if created fully formed and ready to go by specially trained metadata elves (close relatives of those who helped the shoemaker).

No metadata elves were involved in the creation of the Hart images online. Metadata elves are mythical. Rather, as with the workers who drilled and blasted the tunnels in the Sierras, it was the hard work of a coordinated group. First, a professional conservator had to examine all the cards to make sure they could withstand the digitization process. Then a librarian created the descriptive metadata, and finally the photographer carefully scanned each card, front and back. The total time for the project—five weeks. Now take this basic view of the process and think about the time and work to place more than 150,000 images online in the digital library.

The 75,000 images from the Southern California Edison Project represents more than 10 years of work, both creating the metadata and images. The Maynard Parker collection, five years; the Otis Marston collection (see an earlier blog post about that here), two years of scanning. Indeed, to get the Huntington Digital Library up and running took two and half years of planning and preparation. In the past it was frequently said that we were so far behind the curve, technologically speaking, that we didn't even see the curve. The metadata elves certainly would have been useful at that point. Through hard work, however, we have caught up to the curve and now continue laying down track deep into the digital realm. And, as with the Central Pacific Railroad, we have laid our track on a firm railbed. We are set to expand and build on what has been accomplished so far. Keep an eye on the HDL, there will be great additions coming down the track soon.

Alfred A. Hart, "Rounding Cape Horn," stereograph, ca. 1868. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Mario Einaudi is the Kemble Digital Projects Librarian at The Huntington.