The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

EXHIBITIONS | All the World’s a Page

Posted on Fri., Nov. 8, 2013 by

The newly renovated Main Hall of the Library. Photo: Tim Street-Porter.

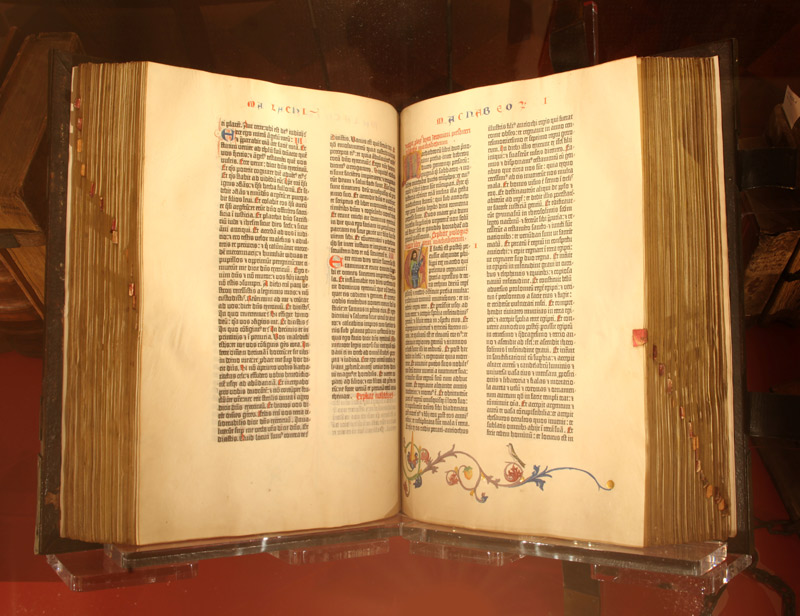

As you enter the Library’s Main Hall and walk straight ahead, one of the first things you’ll see is a familiar treasure underneath a Plexiglas sign reading “A Landmark in Printing.” The Gutenberg Bible (ca. 1455) anchors one of 12 sections in “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times: Highlights from the Huntington Library,” the permanent exhibition opening tomorrow after an 18-month renovation of the building.

This new installation is different from what you might remember of the old display, when the Bible and other treasures—such as the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Shakespeare’s First Folio, and Audubon’s Birds of America—stood out as solitary tomes. You’ll still find these same treasures, but now they have come down off their pedestals to mingle with about 150 other books, manuscripts, photographs, and maps from the 9 million strong library of The Huntington.

The Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1455. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The works had become so iconic that you had almost ceased to think that a human being had created them,” says David Zeidberg, the Avery Director of the Library, “so we wanted to show that these books were made by real people with the same sort of foibles that we have.” In fact, Johann Gutenberg eventually went bankrupt and lost his printing business to his partners.

By placing the Gutenberg Bible in its time—alongside other works of the late 15th century—curators have brought new dimension to it while also bringing lesser known treasures into fuller relief, including copies of Dante’s Divina Commedia (1472) and Filippo Calandri’s Aritmetic (1492), one of the earliest illustrated textbooks.

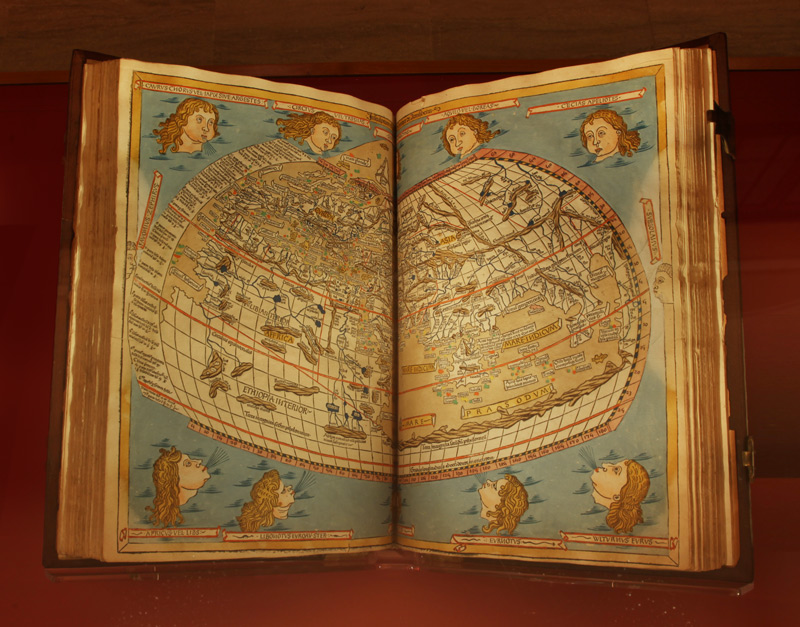

“Each of the 12 sections can be viewed as a little exhibition in its own right,” says Zeidberg. So “A Landmark of Printing” also situates the Gutenberg Bible in the early days of global maritime exploration. On display is a published letter by Christopher Columbus (1493) and a 15th-century copy of Ptolemy’s Geographia (1486), open to a map representing the ancient Greek geographer’s understanding of the world—a rendering that influenced Columbus as he was planning his first voyage to the New World.

Claudius Ptolemy's Geographia, 1486. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The idea here is to give people a sense of the world in which these key works were produced,” says Zeidberg, “not just have them stand in isolation.”

That world is represented also in a digital display that shows the spread of printing across Europe. Various cities pop up as the map changes over time, depicting the first printing of books in many of those cities.

Audio and interactive stations accompany other sections, such as “A Beautiful Manuscript,” which highlights the 15th-century Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and “A Map of the World,” which showcases a map of Tenochtitlan (present day Mexico City) from a book authored in 1524 by New World explorer Hernan Cortés (1485–1547).

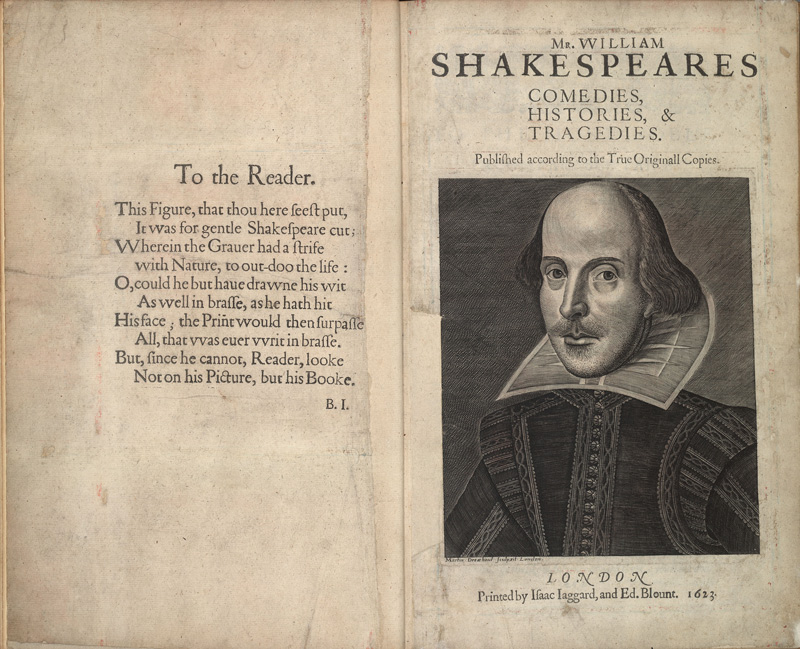

Shakespeare’s evolving world is represented by the First Folio (1623) in a section titled “A Book of Plays by a Genius.” The first known collection of Shakespeare’s plays shares center stage with a text by Galileo (born in the same year as Shakespeare) and a book called A discovery of the Barmudas (1610), the likely inspiration for Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest.

Also on display is a 1611 edition of Hamlet, a play published four times in Shakespeare’s lifetime. The earliest known edition, printed in 1603, is not the version we all have come to know so well. Visitors can pick up a listening device to hear an actor read lines from Hamlet’s soliloquy, including “To be or not to be, I there’s the point.” This is followed by a reading from the better known 1604 edition—“To be or not to be, that is the question.”

Scholars have long speculated that an actor may have pirated the play in 1603 by attempting to reproduce it from memory.

“The current thinking,” says Zeidberg, “is that Shakespeare saw the 1603 ‘bad’ quarto and may have had a hand in the publication of the 1604 ‘good’ quarto.” The 1604 title page states, “newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much againe as it was, according to the true and perfect Coppie.”

The First Folio, also known as the “true original copy,” is the most reliable source of all 36 of Shakespeare’s plays.

Shakespeare's First Folio, 1623. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The exhibition opens Saturday, Nov. 9. It was designed by Karina White with Gordon Chun Design (based in Berkeley, Calif.), who worked together on The Huntington’s award-winning permanent exhibitions “Plants are Up to Something” in The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science and “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World” in Dibner Hall of the History of Science, which adjoins the Library’s Main Hall.

Other sections include “A Masterful Poem” (John Milton’s Paradise Lost); “A Founding Document” (Declaration of Independence); “A Huge Book of Birds” (Audubon’s Birds of America); “An Essay on How to Live” (manuscript of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden); A Civil War Letter (handwritten letter from Abraham Lincoln to Gen. David Hunter, 1863); “A Vote for Women” (handwritten letter from Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1872); “A Draft of a Novel” (manuscript of Jack London’s White-Fang, 1905–06); and “A Portrait of California” (“Coaching” paper for prospective immigrants from China, ca. 1930).

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.