The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

EXHIBITIONS | Some Reassembly Required

Posted on Tue., April 8, 2014 by

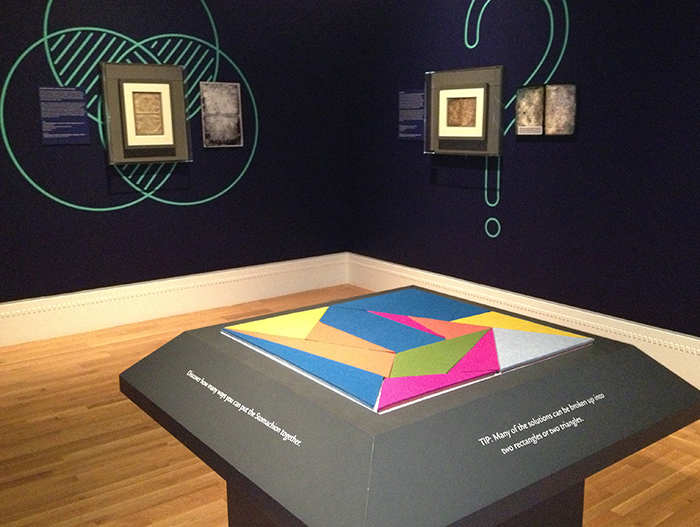

In the exhibition “Lost and Found: The Secrets of Archimedes” visitors can play with an oversized stomachion.

Most people know the Rubik’s Cube, that colorful handful of plastic that has fascinated and frustrated many a puzzle aficionado over the past 40 years.

But have you heard of the stomachion?

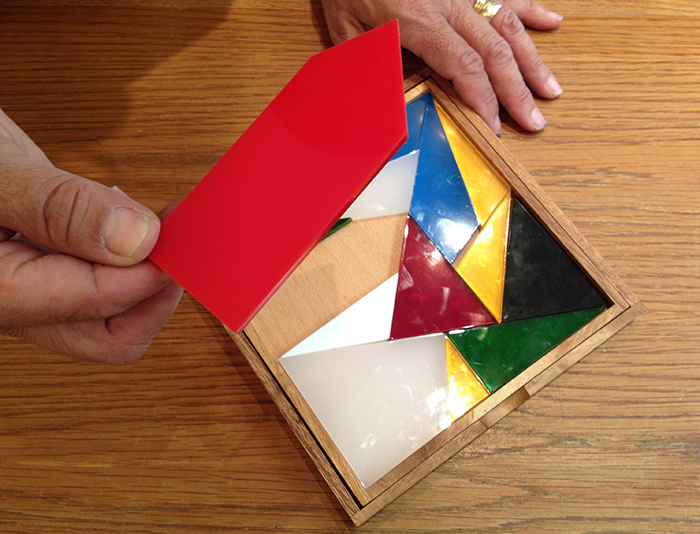

It’s a puzzle attributed to the Greek mathematician Archimedes, and it poses this question: How many different ways can you rearrange the pieces of a square that’s been cut into 14 distinct slices—and still make a square? Seven? Twenty? Going out on a limb with an even wilder guess, could it be—143?

The pieces of the stomachion can be rearranged—get this—in 17,152 ways. It’s a fascinating fact that comes out of the world of combinatorics (more on that, below).

The stomachion is said to be our earliest known mathematical puzzle, found in the astonishingly cool Archimedes Palimpsest, portions of which are now on view at The Huntington.

And if you’re looking for a great story of intrigue, come see “Lost and Found: The Secrets of Archimedes” in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through June 8.

Here are the basics: Archimedes lived during the 3rd century B.C. in present-day Sicily; he was a mathematician, physicist, inventor, engineer, and astronomer and is considered today to be among the world’s greatest classical thinkers.

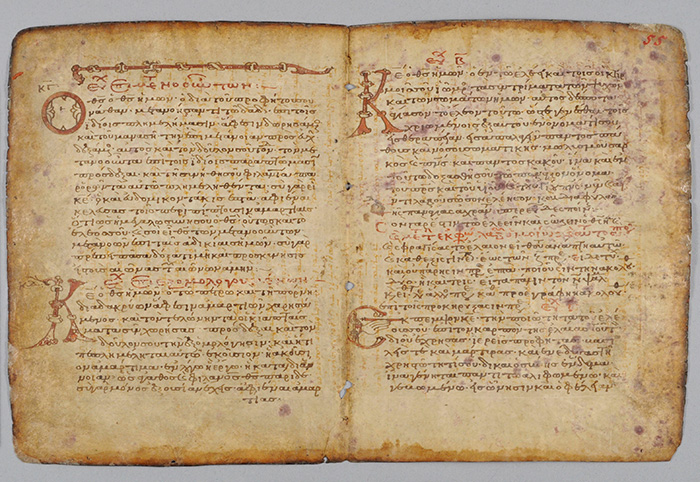

In 10th-century Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), an anonymous scribe copied Archimedes’ mathematical treatises onto parchment. Three hundred years later, a Greek Orthodox monk literally recycled the document to use the parchment for another purpose: He erased the Archimedes text, cut the pages along the center fold, rotated the leaves 90 degrees, and folded them in half. The pages were then bound with other erased manuscript leaves to create a prayer book. This recycled book is known as a palimpsest—referring to a piece of writing that has been erased or scraped off to make room for other writing. “Palimpsesting” was commonplace hundreds of years ago when parchment and paper were hard to come by.

This view of part of the Archimedes Palimpsest shows the prayer book orientation pf the manuscript pages (leaves 55v–50r). Copyright the owner of the Archimedes Palimpsest, licensed for use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Access Rights.

Over the hundreds of years that followed, successive owners held onto the prayer book, not knowing of the Archimedes underwriting until the late 1800s. It was at that time that Archimedes scholar Johan Ludvig Heiberg saw the book in Istanbul and recognized seven treatises by Archimedes underneath the prayers; he had discovered the oldest surviving source for Archimedes’ writings. He transcribed as much of the text as was possible, and he took photographs, which turned out to be crucial to the ultimate discovery of the significance of the book.

But little is known about what happened to the palimpsest during the 20th century; after Heiberg’s discoveries, it disappeared for decades. What is known is that over these “lost years” some of the pages went missing, mold set in, and illustrations of the evangelists, forged to look medieval, had been painted on some of the pages. There is some suggestion that a book dealer may have added the illustrations to make the Palimpsest more marketable. Eventually, the book was put up for auction and sold in 1998. The buyer then turned around and handed it to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore for conservation, imaging, and transcription, a painstaking process taking the better part of 12 years.

“It was in horrible condition, having suffered a thousand years of weather, travel, and abuse,” said Will Noel, Archimedes project director and then curator of manuscripts and rare books at the Walters Art Museum, in a 2011 news release. The text was filthy; it had been singed by fire and dripped on with wax. In fact, before imaging could begin, the manuscript had to be stabilized. It took four years alone simply to disassemble and remove adhesive from the folds, given its fragility.

“I documented everything and saved all of the tiny pieces from the book, including paint chips, parchment fragments, and thread and put them into sleeves so we knew what pages they came from," said Abigail Quandt, the Walters Art Museum’s senior conservator of manuscripts and rare books.

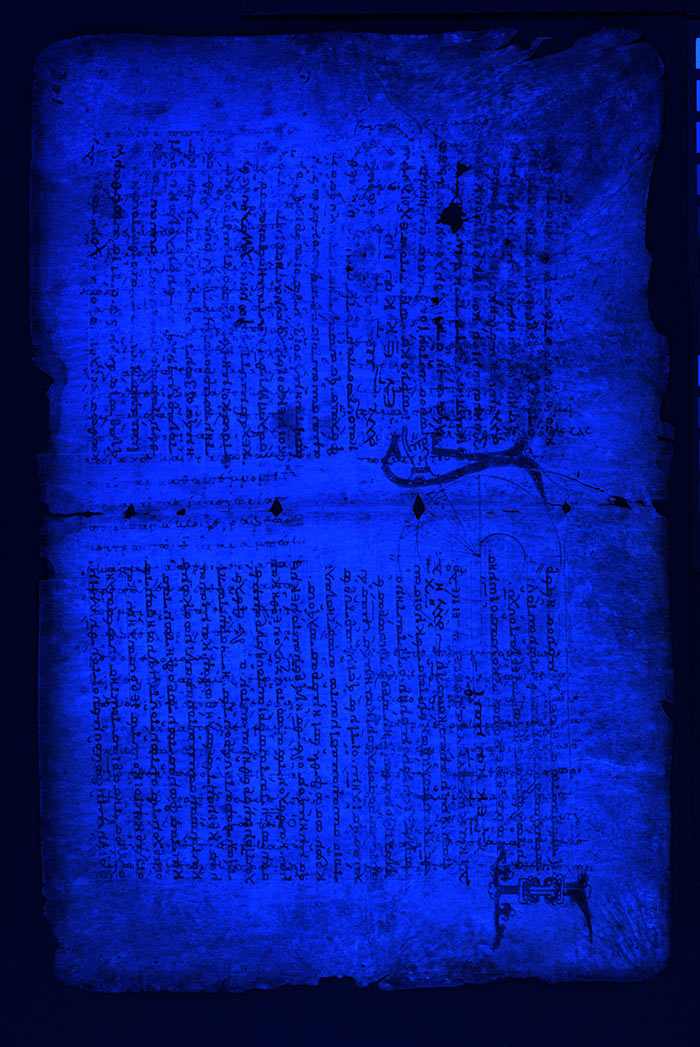

Turned 90 degrees and under ultraviolet light, the Archimedes Palimpsest reveals spiral lines of Archimedes’ original text (leaves 98v–102r). Copyright the owner of the Archimedes Palimpsest, licensed for use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Access Rights.

Once stabilized, the book went through a series of high-tech imaging processes to coax out the ancient text and diagrams. Teams of scientists combined different light sources—ultraviolet light, strobe, and tungsten—to get the job done. Additional imaging, using powerful synchrotron radiation at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, showed writing that had been hidden beneath religious paintings added in the 20th century. Then came the big reveal.

The Palimpsest contained a copy of a previously unknown Archimedes work, including the stomachion. And why is it called that? It’s not clear when the puzzle got its name, but some historians believe that it was a playful descriptor, as in “this puzzle is so maddening, it’s given me a stomach ache!”

Did Archimedes create the puzzle? That’s not clear, but it is the basis for an increasingly important area of science—combinatorics, the study of assembling and reassembling a specific set of objects. Combinatorics, it turns out, is critical in modern computing and for solving all sorts of problems—from coordinating and optimizing flight schedules to managing space use on a factory floor to synchronizing traffic lights to creating new types of chemicals.

Want your own? We’ve got ’em. And have at it! Might want to make sure you’ve got some Alka-Seltzer on hand first.

The puzzle is available for purchase in The Huntington’s Gift Shop.

Susan Turner-Lowe is vice president for communications at The Huntington.