The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

EXHIBITIONS | Twenty-One Missions, Many Legacies

Posted on Thu., Nov. 21, 2013 by

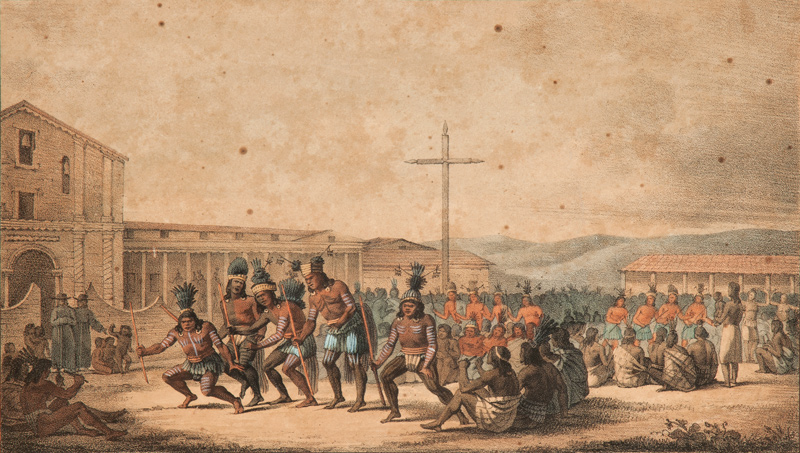

On display in “Junípero Serra and the Legacies of the California Missions” is this print showing Indians performing music and dance at Mission San Francisco. From Louis Choris, Voyage pittoresque autour du monde, 1822, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, gift of Carol L. Valentine.

What is your connection to California’s missions? Did they inspire the style of house you live in? Do they symbolize steadfast faith? Do they conjure up an idyllic early California yielding bountiful produce from a smog-free landscape? Or do they prompt you to wonder about their impact on the descendants of mission Indians?

These questions might come to mind as we mark the 300th anniversary of Junípero Serra’s birth this weekend. He is at the center of the exhibition “Junípero Serra and the Legacies of the California Missions,” which runs through Jan. 6, 2014, in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries.

Serra, born Nov. 24, 1713, was an evangelist and preacher, first in his native Mallorca in Spain, then in Mexico, and finally in California, where he devoted himself to converting the Indians to Catholicism. Serra founded nine of the 21 missions, beginning with the first in 1769. They became dynamic and productive communities, but the missionary efforts also had negative consequences. Mortality rates climbed after Indians moved onto mission land. Also, Indians helped build the missions and make them vibrant centers, but many who relocated to the missions were forced to convert to Catholicism, and they often lost touch with their own traditions. And when the missions were dismantled in the 19th century, Indians became marginalized, forced onto the most unproductive land.

The last gallery of the exhibition includes a series of video interviews titled “Contemporary Voices.”

Near the end of the exhibition is one of its most thought-provoking sections. “Contemporary Voices” is a series of video interviews with descendants of California Indians that puts a human face on the missions’ complicated legacy.

Andrew Tautimez Salas, chairperson of Kizh Nation/Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians, finds no beauty in the missions. In the interview, he stated that when he visits the graves of relatives, he thinks of “the bad that they went through there.” He said he believes his calling is to “carry the legacy of our history, to spread the word of our true identity.”

Linda Yamane with her Ohlone ceremonial basket, 2012. Courtesy of the artist, supported by a grant from the Creative Work Fund.

“Contemporary Voices” is just a few steps away from a striking example of Indian identity: a ceremonial basket crafted by Linda Yamane, a Rumsen artist. The basket exterior is deep red and white and made of willow, sedge, bird feathers, and olivella-shell beads. Completed in 2012, the basket took Yamane more than two years to make and is believed to be the first basket of its kind created in more than 200 years. It contains 12,500 stitches, 110 willow sticks, approximately 400 sedge strands, and a 60-foot coil. The basket is a remarkable transformation of natural materials into an object that resonates beyond the everyday.

In her interview, basket maker Yamane said she knew nothing about the Rumsen Ohlone cultural traditions or language. “They were gone,” she said. “We don’t know today how the basket was used.” She came to feel her basketry was “a prayer…. It helps connect us within the cultural community as a group of people together.”

Anthony Morales, chairperson of Gabrieleño/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, said in his interview, “There’s a misconception that we were a myth.… But here we are today living in regular society.” He said he doesn’t let his Catholicism interfere with his cultural traditions and vice versa. “I honestly believe our ancestors lived in both religions. It still boils down to just one creator, one supreme being,” Morales said.

Yet another interview features Andrew Galvan, who is an integral part of the Serra legacy: The curator of Mission Dolores belongs to an Ohlone family that is devoutly Catholic. He said some of his friends ask, “How is it possible that you can sponsor, promote Junípero Serra to be named a saint?” He said he answers, “I know him, study him, pray to him.… He brought Christianity to the Native Americans.” (Galvan is a member of the board of directors of the Junípero Serra Cause for Canonization.)

Galvan said he believes Serra will not achieve sainthood without some sort of recognition and resolution of the California missions’ impact on the descendants of mission Indians. He stated, “The miracle would be the reconciliation of a people who have been thrown out of the places that they built.”

The videos were made by Form follows Function, a collaborative media studio creating nonfiction, short-format, place-based videos.

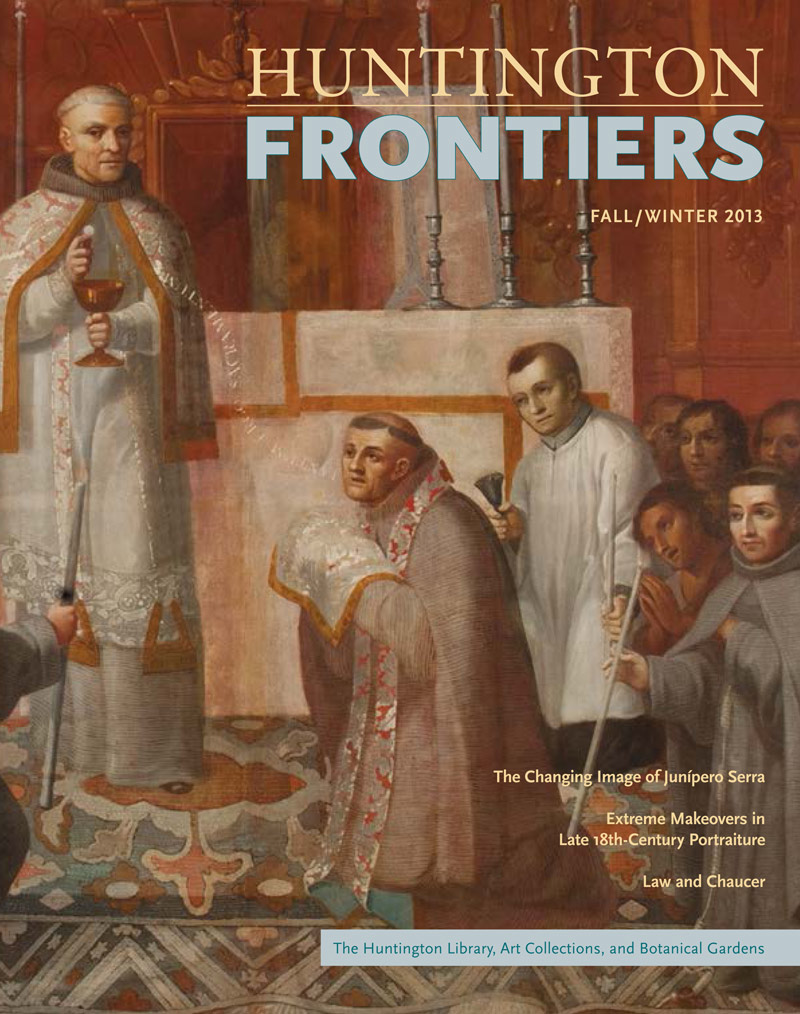

For more on Junípero Serra, you can read “Between a Rock and a Crucifix: Father Junípero Serra in His Own Day,” by Steven W. Hackel, in the most recent issue of Huntington Frontiers magazine. It is an excerpt from his new book, Junípero Serra: California’s Founding Father (Hill & Wang, 2013), available for purchase in The Huntington’s Store.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles-based communications consultant.