Posted on Wed., Jan. 30, 2019 by

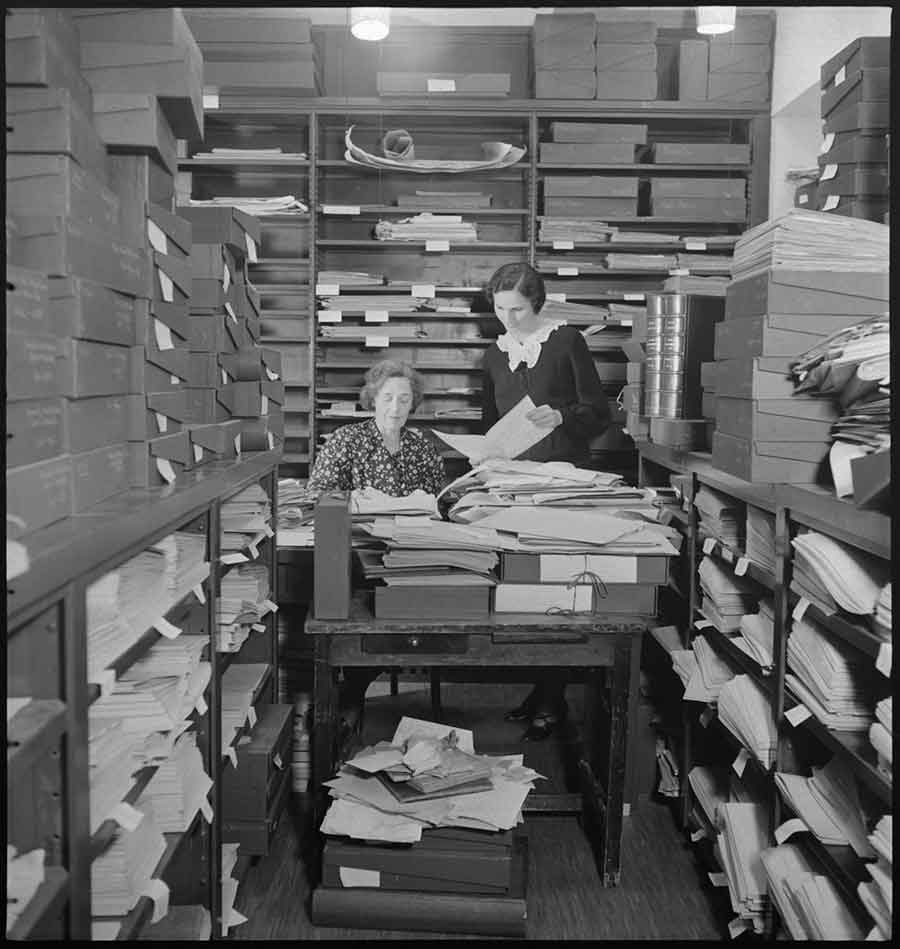

Norma B. Cuthbert (left) and Haydée Noya cataloging manuscripts in the Huntington Library, February 1938. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Did you vow to tidy up in 2019? If the current mania for organizing consultant Marie Kondo is any indication, you're not alone. For libraries, of course, creating order is a year-round preoccupation—you might even say it’s their essence.

I am the editor of the Huntington Library Quarterly, which means I find joy in helping scholars share their discoveries. A recent essay in the HLQ by Markman Ellis, professor of 18th-century studies at Queen Mary University of London, uses the correspondence of Elizabeth Montagu at The Huntington to reflect on how people have organized and saved papers over time.

People have been filing nearly as long as they have been writing things down. But, until pretty recently, you didn’t put things in a file; you put them on a file. Take, for example, a throwaway line in Shakespeare’s play All’s Well That Ends Well: as his pockets are searched for a letter, a character remarks, “either it is there, or it is upon a file with the Duke’s other letters, in my tent.” (Yes, Shakespeare did talk about filing. Just the once.)

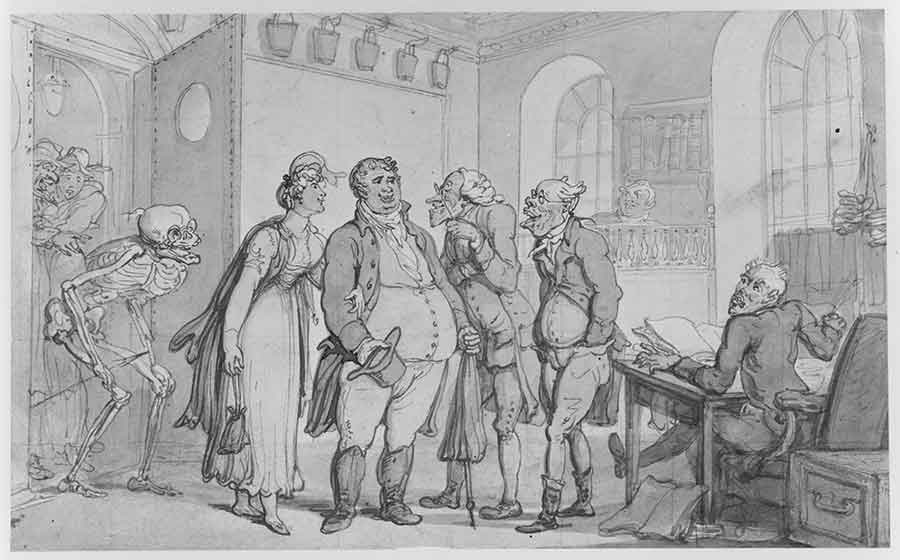

This early 19th-century comic print shows a file with papers strung on it, hanging from the wall at the far right. (The print pokes fun at a husband who has been urged by his wife to get life insurance; death follows close at his heels.) Thomas Rowlandson, “The Insurance Office,” an illustration (rendered here in black and white) in William Combe, The English Dance of Death: From the Designs of Thomas Rowlandson with Metrical Illustrations (London, 1815–16). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

So, what does it mean to put things on a file? Let’s turn to Samuel Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary for help: “FILE. n. s. [ file, French; filum, a thread, Latin.] . . . A line on which papers are strung to keep them in order.” In fact, look at just about any English-language dictionary before the mid-20th century, and you’ll discover that a file is a thread, string, wire, or pointy object laced through papers.

Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), the focus of Ellis's research, was an elite Englishwoman who created an influential social network in the second half of the 18th century. She did this partly by hosting salons but mostly by writing letters. Scores upon scores of letters. Of those that survive (around 8,000 worldwide), 6,923 are at The Huntington. Montagu's vast correspondence helps researchers portray her world in pinpoint detail.

In addition to their content, the letters themselves tell a story. Here’s what Ellis saw when he looked very closely at Montagu’s letters: little holes from being strung on a file. In the same folder, there is another copy of the same letter, probably made by Montagu’s personal secretary. It has two holes in the same place, about midway down the left-hand margin. Were these filed together?

Left: Holes in the margin of a letter from Elizabeth Montagu to Gilbert West, Sandleford, October 4, 1753, MO 6702 A, Elizabeth Robinson Montagu Papers. Right: Holes in the margin of a copy of the same letter; the copy (MO 6702 B) was probably made by Montagu’s personal secretary. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When the letters got to The Huntington, the catalogers here reorganized them, in a clever way, using the filing technologies of the mid-20th century. First, they put them in alphabetical order by author and numbered them (all the call numbers start with the prefix MO for Montagu and count up from 1 to 6,923).

To give researchers different ways of exploring the letters, they typed up file cards for the catalog listing them by author and then refiled them chronologically in file folders. So, if you were, say, studying a particular poet, you could easily find all the letters by her in the card catalog in a single sequence and call them all up. But if you were tracing how ideas develop over time, then you could read through the folders chronologically to mark subtle shifts as Montagu’s circle discusses them.

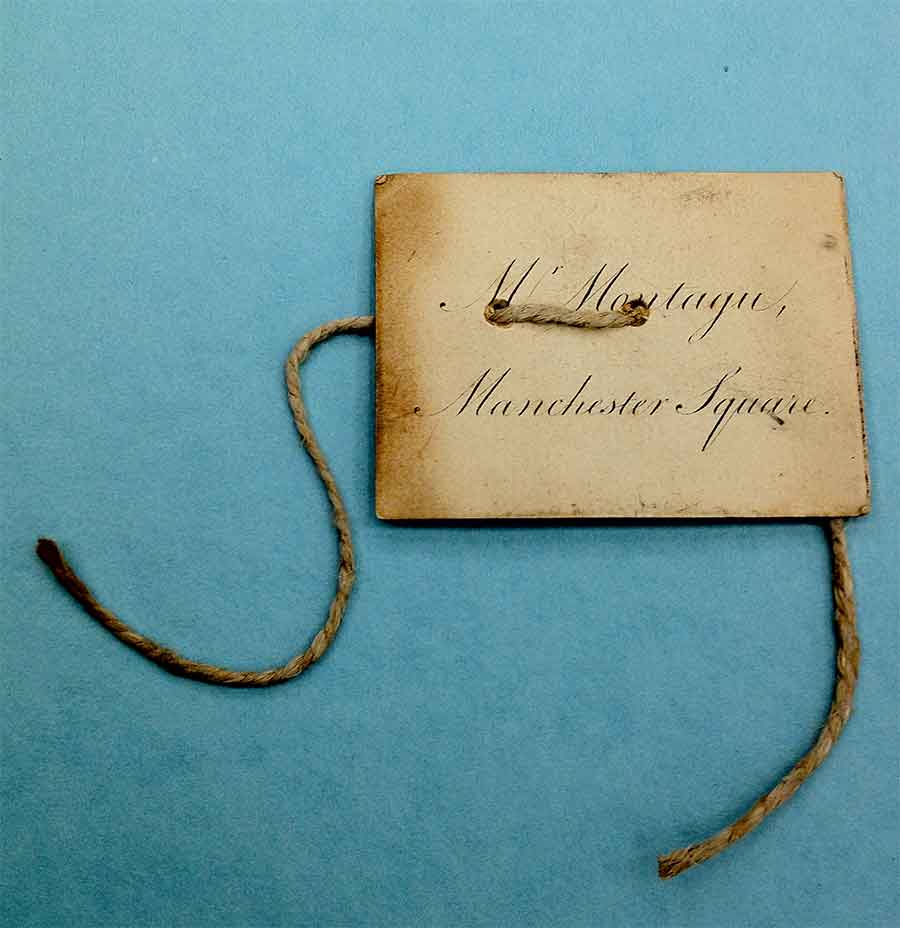

As far as we can tell, Montagu, and then the people who organized her papers for publication after her death, filed by correspondent. Ellis reports on a few tantalizing clues, in addition to those holes. Among the bits and bobs that traveled with the collection as it moved from her family to her editors and finally to The Huntington, for example, is a visiting card reading “Mr Montagu, Manchester Square” (probably her nephew and adoptive son, Matthew Montagu). It was likely used to label a set of letters from him, with rough twine threaded through it. Or rather, a file threaded through it.

Filing tag made from printed visiting card of Mr Montagu Manchester Square, ephemera, MO 6922 (13), Elizabeth Robinson Montagu Papers. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Markman Ellis.

Humanities scholars are interested in how people organized information in the past because this tells us about their habits of mind—their intellectual world. When we put facts or things in order, we give them meaning and priority. We say: We care about this because it came first, or because this person made it, or because there is a lot of it, or because there is only one.

Today, you can search the online finding aid of Montagu letters by typing in any keyword that comes to mind. Every search is its own reordering of the collection. How will you organize it?

Markman Ellis’s essay, “Letters, Organization, and the Archive in Elizabeth Montagu’s Correspondence,” appears in a special issue of theHuntington Library Quarterlyedited by Nicole Pohl: “‘The Commerce of Life’: Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800).”

Ellis cites in his article a blog post by Heather Wolfe, curator of manuscripts and archivist at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., in which she writes about filing in the 17th century.

Sara K. Austin is the editor of theHuntington Library Quarterly.