The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Finding Molokai

Posted on Mon., Jan. 30, 2017 by

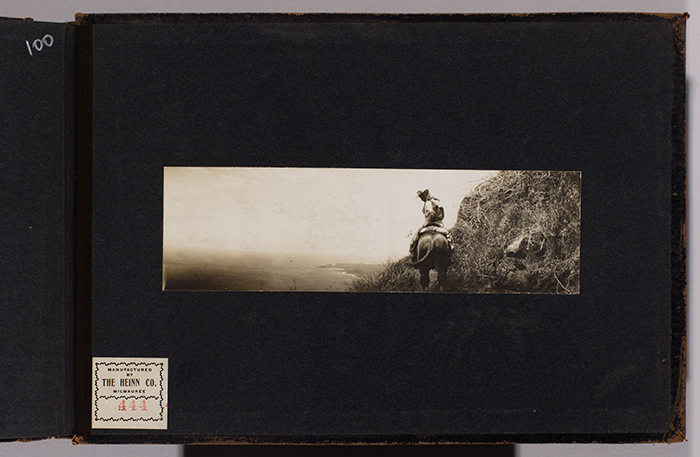

Charmian London on horseback at Molokai pali (cliff) with Kalaupapa peninsula visible in the distance, July 1907. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Charmian London on horseback at Molokai pali (cliff) with Kalaupapa peninsula visible in the distance, July 1907. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.At daybreak on a steamy morning last August, my husband dropped me off at the Kalaupapa trailhead on the north shore of Molokai and waved goodbye.

A year earlier, I had convinced my husband and two children that this tiny, rural, and impossibly beautiful Hawaiian island was the vacation destination of their dreams. But as I stood at the edge of the pali (cliff) that plunged 2,000 feet into the sea and contemplated the cluster of warning signs—Falling rocks! No public medical facilities! No one under 16 years of age allowed! Proceed at your own risk!—I felt a twinge of fear.

The adventure writer Jack London and his wife, Charmian, had lured me to this spot. In 1907, the irrepressible duo set off from Oakland, California, on a widely publicized round-the-world trip. Sailing a custom-built, 45-foot-long sloop named the Snark, the Londons headed for Hawaii as their first port of call. Never mind that they and their ragtag crew knew nothing about navigation. London, a voracious reader since his youth, consulted “how to” books en route. After 27 days at sea, the Snark drifted into Honolulu harbor. The press had already given them up for dead.

As I hiked alone down the rugged trail, I encountered makeshift shrines along the way. Tucked into rocks, nearly hidden by ferns, were offerings of shells, plastic Madonnas, horseshoes, folded-up prayers. Markers for the two dozen switchbacks ticked by, one by one. Several deer warily eyed my progress, and a feral pig crashed across my path. At last I stood on a deserted beach looking across a dazzling bay toward a peninsula of land. Here it was: the place Jack London called “the pit of hell, the most cursed place on earth.”

Looking down on the Kalaupapa peninsula from Molokai pali, August 2016. Photo by Jenny Watts.

Looking down on the Kalaupapa peninsula from Molokai pali, August 2016. Photo by Jenny Watts.Its breathtaking beauty notwithstanding, Kalaupapa’s dastardly reputation was justly earned. King Kamehameha V enacted a law in 1865 that criminalized sufferers of “leprosy” or what is now known as Hansen’s disease. The government arrested the ill, shipped them off to the isolated colony of Kalaupapa, regardless of their age, and then threw away the key. Over the next 100 years, at least 8,000 people died in enforced isolation. Residents were not free to leave until 1969.

Jack London received an invitation to visit the colony while hobnobbing with Honolulu’s elite. By 1907, the Board of Health (the entity that governed Kalaupapa) had made significant medical and humanitarian strides. Even so, sensationalist accounts abounded, and Pacific Rim boosters worried about the negative impact of these stories on Hawaii’s budding tourist trade. Who better, they reasoned, to help dispel the myths than renowned author Jack London?

Jack and Charmian were aware of Kalaupapa’s notoriety, and they leapt at the chance to take a tour. The sightseeing also fit into London’s scheme of writing articles to finance the trip. An accomplished amateur photographer, London knew that any pictures he supplied substantially increased his fee. (His standard rate of 15 cents a word and five dollars per published photograph was a pretty sweet deal.) To that end, London packed seven cameras: four portable folding models, two Kodak panoramas, and a stereoscopic camera with a state-of-the art lens.

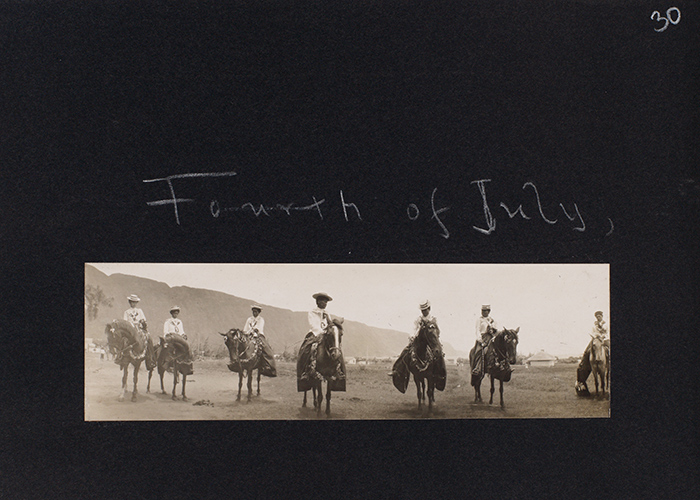

Women Pa’u riders on horseback and wearing traditional costumes, Kalaupapa, Molokai, July 4, 1907. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Women Pa’u riders on horseback and wearing traditional costumes, Kalaupapa, Molokai, July 4, 1907. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.I had only an iPhone in my pocket as I waited for the bus that would take me on a historical tour of the area. A few National Park Service vehicles drove past. (Kalaupapa became a National Historical Park in 1980.) From what I could see, the place was as eerily quaint and idyllic as it had appeared a century earlier when Jack and Charmian rode in on horseback.

The pair stayed five days, and their hosts pulled out all the stops. They attended Fourth of July festivities at the racetrack, where the “Horribles” (as the residents jokingly called themselves) gathered to compete and bet. London marveled at the handsome P’au riders parading in traditional dress. He reveled in the games and flamboyant costumes and took a series of panoramic photos to record the events. “The chief horror of leprosy,” London reported in a glowing account that ran in Women’s Home Companionin 1908, “obtains in the minds of those who have never seen a leper and who do not know anything about the disease.” Kalaupapa’s residents were, he concluded, a “happy lot.”

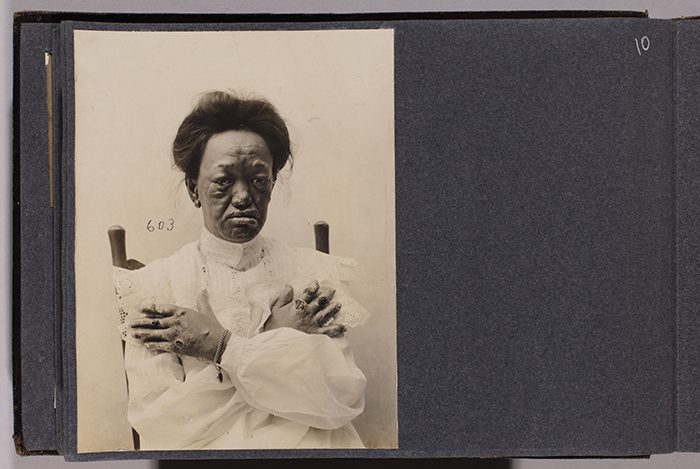

Miss Kanoelani Hart (case 603), age 22, from Waimea, Hawaii, July 3, 1906. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Miss Kanoelani Hart (case 603), age 22, from Waimea, Hawaii, July 3, 1906. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Several of the pictures pasted into three albums stamped “Molokai” in The Huntington’s Jack London archive belie the writer’s upbeat article. There are many photos of Fourth of July revelers, as well as shots of the remarkable setting and people posed in front of well-kept buildings with tidy lawns. But none of the afflicted came to the settlement by choice, and some of the government-issue portraits included in the archive tell a darker tale. In these, the sitters’ expressions are frozen in a paralyzed grimace, and their eyes look inconsolably sad.

I reflected on these pictures—of children, in particular—as six fellow tourists and I meandered down the nearly deserted roads in an air-conditioned van. We visited a bookstore and a “bar,” each run by one of the 15 remaining residents, who seemed to resent the intrusion. Jack and Charmian enjoyed a warmer welcome on their carefully orchestrated tour. They were taken into the medical and communal facilities shared by the then 800 residents, treated to concerts, and shown the ancient archeological sites. They visited the grave of Father Damian, the sainted Belgian priest. We did, too. Father Damian made Molokai his life’s work before succumbing to Hansen’s disease at the age of 49.

Hiram Pahau (case 558), age 7, from Ala Moana near John Ena Road, admitted Oct. 27, 1905. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

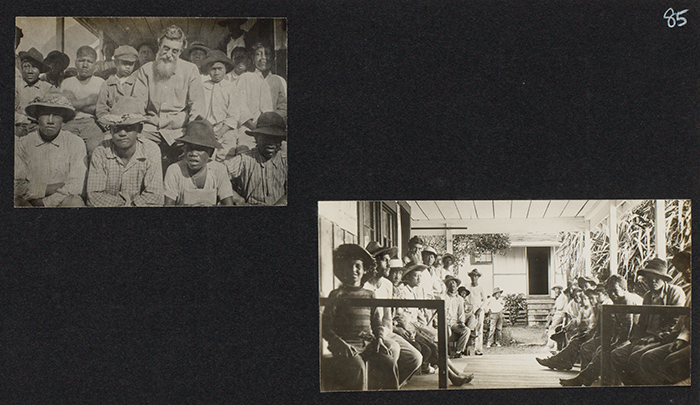

Hiram Pahau (case 558), age 7, from Ala Moana near John Ena Road, admitted Oct. 27, 1905. Jack London Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Next to Father Damian’s flower-bedecked grave was that of Brother Joseph Dutton, a man the Londons mentioned in passing. Dutton served with the 13th Wisconsin Infantry during the U.S. Civil War. He spent two subsequent years digging up and reinterring Union soldiers’ remains. A disastrous marriage and heavy drinking followed before he took Catholic orders and showed up, unannounced, in 1886 on Kalaupapa’s shores. He spent the rest of his life, 44 years all told, seeking penance for his past, caring primarily for the colony’s male orphans.

The tour guide dropped me off where I had begun my journey six hours earlier. This time, the only way out was straight up. Even though I was glad I’d come, the superficial overview made me uneasy as I contemplated the weight of Kalaupapa’s history. Even Jack and Charmian had privately admitted their misgivings, and Jack later wrote a dramatic short story, “Koolau the Leper,” that enraged his hosts.

Yet it was Brother Dutton, not the Londons, I thought about as I struggled up the trail. When asked what could be done to help, Dutton’s reply was simple and profound. One does not have to travel far to encounter suffering or charity: “There are Molokais everywhere.”

Two images of Joseph Dutton on Molokai, ca. 1905. In the image on the left, Dutton sits with a group of Hawaiian men and boys. In the image on the right, Dutton is seen with a group of men on a porch of what may be the Baldwin Home for men and boys that Dutton founded on Molokai.

Two images of Joseph Dutton on Molokai, ca. 1905. In the image on the left, Dutton sits with a group of Hawaiian men and boys. In the image on the right, Dutton is seen with a group of men on a porch of what may be the Baldwin Home for men and boys that Dutton founded on Molokai.You can view the Jack London Photographs and Negatives collection online at the Huntington Digital Library.

Related content on Verso:

A Deep Dive into Jack London’s Life (Sept. 19, 2016)

Jack and Charmian’s National Park Adventures (July 22, 2016)

Jack London and the Rose Parade (Jan. 1, 2016)

Jack London, Public Intellectual (Sept. 22, 2015)

To Build a Fire (Jan. 10, 2014)

The Star Rover (Jan. 12, 2012)

A Friend to Jack London (Sept. 15, 2011)

Jenny Watts is curator of photography and visual culture at The Huntington.