The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Into the Fold

Posted on Mon., April 4, 2016 by

One of The Huntington’s partner schools is Esteban E. Torres High School in East Los Angeles. Last month, students from their Engineering and Technology Academy visited The Huntington as part of a yearlong program exploring the ancient Japanese art form of origami. Torres students toured The Huntington’s Japanese Garden to learn about Asian garden aesthetics and then visited the historic Japanese House, where they learned how to fold a kimono. As part of the program, Manan Arya, a Ph.D. candidate in aerospace engineering at Caltech, went to Torres to give students lessons in the scientific principles behind origami.

Students at one of The Huntington’s partner schools, Esteban E. Torres High School in East Los Angeles, are taking part in a program exploring the Japanese art form of origami. Photo by Martha Benedict.

Manan Arya was about to demonstrate how origami folding techniques could be used with materials other than paper. He held up a lightweight, foot-long cylinder made from glass fibers. Two different substances were in the matrix binding the fibers together. “See these yellow regions,” said Arya, “they contain a resin epoxy and are very stiff, like the material used to make a boat or a custom car. And these white regions contain a soft silicone, so you can do this,” he said.

Arya deftly folded the cylinder into a small, square packet. Then he threw the packet in the air. As soon he loosened his grip, the packet returned to its original shape, and the cylinder floated back into his hands.

“Oh! Wow,” exclaimed the students.

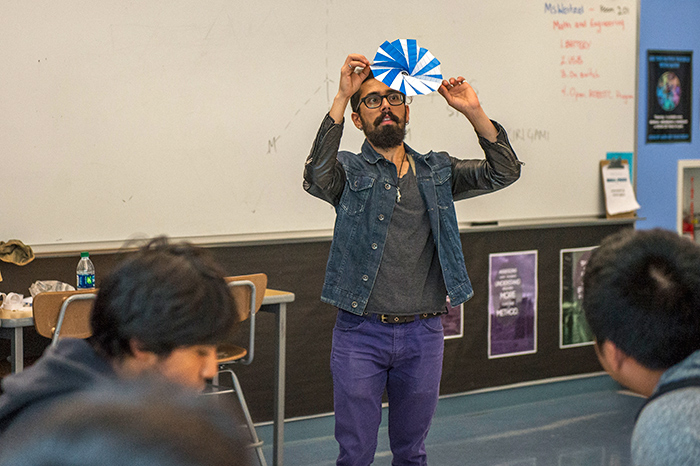

Manan Arya, a Caltech graduate student, designs and tests methods for packaging and deploying large, thin structures for spacecraft. Arya taught engineering students at Esteban E. Torres High School some of the origami folding techniques that inspire his work. Photo by Martha Benedict.

Arya smiled. He hoped that teaching the teens about the scientific concepts behind origami would show them how engineering can help resolve real-life technology challenges. At Caltech, Arya uses origami-inspired techniques to design and test methods to package photovoltaic arrays, solar sails, and sunshields that can be deployed into space. (Origami folds are also used in the design of medical devices, such as tiny collapsible heart stents that can be threaded into a blood vessel and then opened up to restore blood flow.)

In two previous lessons, students learned to call a crease at the top of a piece of paper a mountain and one at the bottom, a valley. They studied a pattern with a single vertex and then moved on to the beech-leaf pattern, with four vertices all in a line.

For the current lesson, they were brainstorming on how they could apply the mechanics and physics of paper origami and use them on thicker materials. With paper, the creases occurred at precise points, with all the axes on the same plane. But if you could zoom in on the paper, you’d realize that making such a hard crease caused the fibers at the top of a fold to pull apart and those at the bottom to compress.

Students attached wooden tiles with cloth tape to create a Miura-Ori model, an example of which is seen in the foreground. Photo by Martha Benedict.

“I can’t do that with metal, I can’t do that with carbon fibers, or wood,” said Arya. “So how do we start thinking about folding thicker things without stretching or compressing them?”

“A hinge?” proposed one student.

“Right,” said Arya. “I use a hinge, like a door hinge. But we need to accommodate for using thicker materials. If I want a mountain over here, I put a hinge on the top, and if I want a valley, I put a hinge on the bottom. This is called the axis-shift method, because you shift the axis of these hinges from the middle where they are on paper, to the top or the bottom.”

The students listened with rapt attention.

Then Arya told them that they were going to use the axis-shift method to create a Miura-Ori model, like the one that was circulating around the classroom. Miura refers to Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura, who invented the technique; ori means a fold. The Miura-Ori method is a way of folding a flat surface into a smaller area. The model Arya brought to class was made from thick wooden tiles. Students took turns holding the model, gazing in amazement as the tiles elegantly closed in on themselves and opened back up.

Origami techniques can be used with wood or with composite materials, like this cylinder made from glass fibers, mixed with a stiff resin epoxy in the yellow areas and a soft silicone in the white regions. Photo by Martha Benedict.

The teens reached into a cardboard box and took out four wooden pieces. Each tile was made from two pieces that had been cut by laser into a trapezoid shape and glued on top of one another. Arya demonstrated how to position the tiles and where to use cloth tape to attach some of the sides as a sort of membrane hinge. He went around the room, checking on their progress.

“You got it,” he said to one group of students. Another teen had set his Star Wars: The Force Awakens cap next to his model. “Kylo Ren has it,” quipped Arya, referring to the movie’s sable-clad bad guy.

Once they were finished, Arya had the students bring their creations to a table where they attached them all into a single model—a replica of the Miura-Oribeing passed around. Looks of pride and satisfaction washed over their faces.

This spiral pattern comes from a family of fold patterns called flashers. It allows a certain distance between each fold, accommodating the thickness of the material. Nature uses similar spiral patterns in sunflowers and snail shells. Photo by Martha Benedict.

The bell rang and the students left for the next period. For some, the impact of what they had learned extended beyond the classroom.

Sophomore Kenneth Morales had all but given up on school. He originally wanted to study math and physics, but found that even his advanced placement classes bored him. “I decided not to attend college, not even to apply,” said Morales.

The origami class changed things. Arya had shown him how engineering could transform a simple art form like origami into a technique for exploring the farthest reaches of our universe. Yes, it involved math, but it was also a creative process that helped to resolve real-life challenges.

“This class was cool,” said Morales.

Now he’s decided he’ll apply to college after all.

Torres students including Kenneth Morales (right) work with Robert Hori (left), The Huntington’s gardens cultural curator and program director, to fold a kimono inside the Japanese House. Torres engineering teacher Lindsay Weitzel, in black, looks on. Photo by Marissa Kucheck.

The yearlong exploration of origami is being made possible by a generous gift from Frank and Toshie Mosher. Other activities related to origami are planned for later in the year.

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.