The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Fourth of July Fireworks

Posted on Tue., July 3, 2018 by

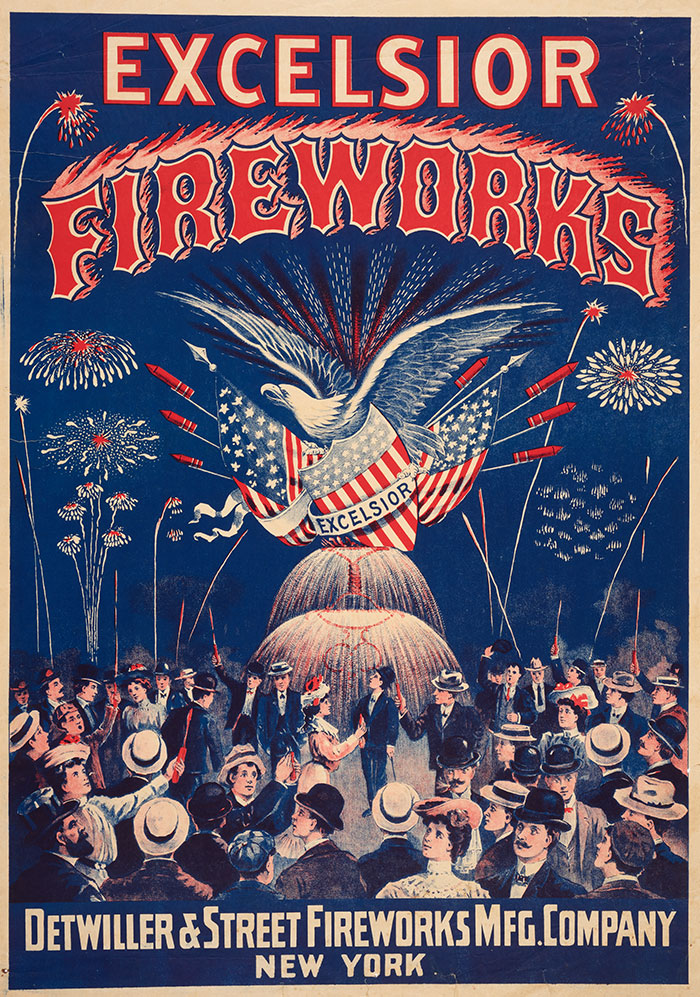

Advertising print for Excelsior fireworks by the Detwiller & Street Fireworks Manufacturing Co. Color lithograph, ca. 1885. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The offerings are explosive: “Balloon Rockets, Devil Bombs, and Barking Dog Cap Bombs, Floating Stars changing colors, making a most beautiful display in the air,” reads a fireworks catalog entry. A promotional poster announces Sanderson & Lanergan, pyrotechnists to Boston, and promises a fireworks show, “[f]urnished as usual in the highest style of the art.”

Independence Day in the United States has been marked with a show of fireworks since the country’s first such celebration in 1777. The Huntington’s Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History provides a fascinating glimpse into how this Fourth of July tradition fueled a booming pyrotechnic industry that thrived through the 19th and early 20th centuries—an industry that used to its advantage the coinciding development of printing and color lithography.

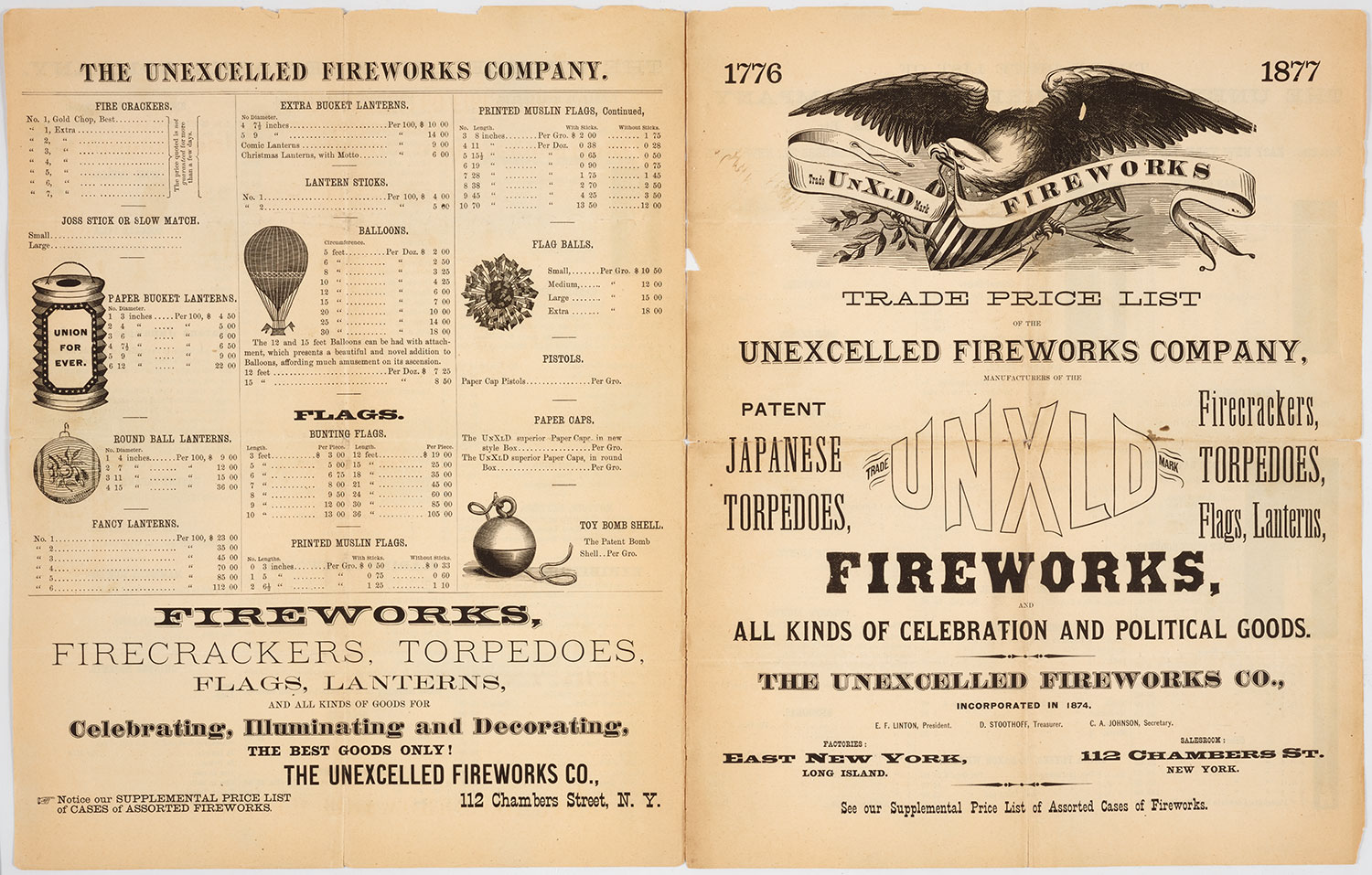

Price list for Unexcelled Fireworks Company, 1877. (Click the image above to see a larger version of it.) Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Sifting through printed artifacts that contain trade catalogs, price lists, and advertising fliers, mainly from East Coast fireworks companies such as Excelsior and Unexcelled Fireworks, David Mihaly, The Huntington’s curator of graphic arts and social history, discusses how such day-to-day items as product posters that once hung in shop windows and promotional trade cards passed out on street corners provide insight into social and printing history and visual culture.

It’s curious that a circa 1880 lithographed trade card shows a hot-air balloon rising above a colorful sea of exploding fireworks. In fact, hot air balloons are a motif that makes appearances on a number of printed artifacts related to fireworks. But why?

Some early balloonists, says Mihaly, became pyrotechnicians as a way to bankroll their hot-air balloon endeavors. They would ignite fireworks while riding in their balloon gondolas and toss them overboard to the delight of audiences below. Such airborne displays were not just relegated to July 4—they included grand exhibitions and parties for the wealthy to celebrate special occasions.

Trade card for Unexcelled Fireworks Company. Color lithograph, ca. 1880. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

What’s almost as striking as the combination of hot-air balloons and fireworks is the sheer number of combined font styles in some of the promotional literature about fireworks. One poster for celebrated pyrotechnist Isaac Edge, Jr., of New York used almost a dozen font styles, sometimes employing several different ones in a single sentence. “The posters would often bombard you with a variety of typefaces to grab your attention,” says Mihaly.

As he sorts through the collection, it’s interesting to see how much a late 19th-century Independence Day celebration resembles a modern one. An Excelsior Fireworks poster produced around 1885 depicts all the familiar components: an eagle, flags, crowds of revelers holding sparklers—all beneath a burst of fireworks.

Manuela Gomez Rhine is a freelance journalist based in Pasadena, California.