The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Frederick Douglass, Celebrity

Posted on Mon., Feb. 20, 2017 by

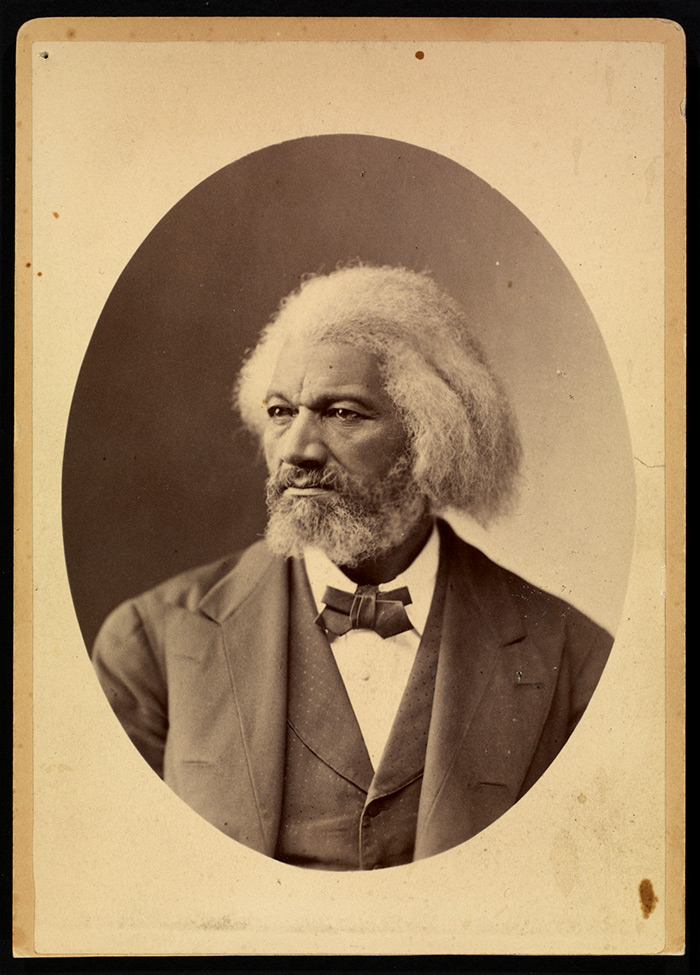

Photographic portrait of Fredrick Douglass, 1876. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

By the time of his death on Feb. 20, 1895, Frederick Douglass had become one of the most celebrated personalities in the United States. Born a slave in Maryland around 1818, he escaped to New York in 1838, married, and soon became an anti-slavery lecturer. He went on to write three acclaimed autobiographies, lectured widely on a range of social causes, and became a statesman and advisor to several presidents.

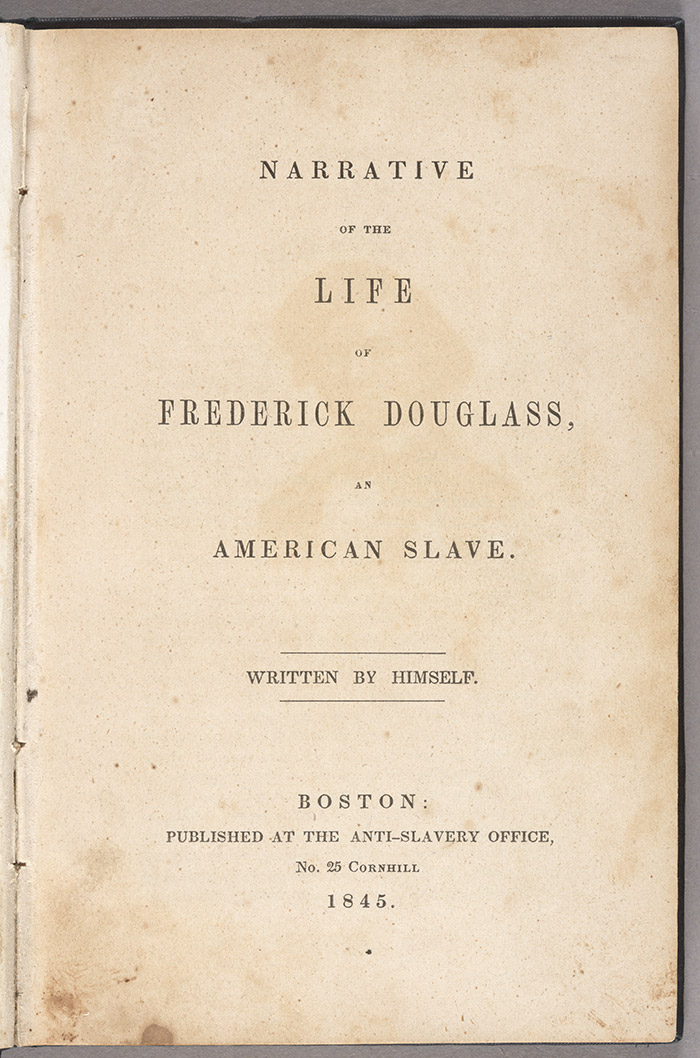

After his first autobiography—Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave—was published in 1845, Douglass became a bona fide celebrity. The celebrity status, of course, was not necessarily tantamount to admiration. His contemporary Stephen A. Douglas, who lost the 1860 presidential election to Lincoln, was outraged that “FRED DOUGLASS, THE NEGRO” dared publicly debate “the illustrious” white politicians of his day.

Yet Frederick Douglass was, as historian John Stauffer has demonstrated in his book Picturing Frederick Douglass, the most photographed American of his time: 160 photographic portraits of him survive (as compared to 130 photographs of Abraham Lincoln).

Title page of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, 1845. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

And, like many other celebrities, he handed out countless autographs. Since the 1840s, celebrity autographs have been popular obsessions. Americans in the 19th century were fascinated with the handwriting of famous men and women, in part because handwriting was viewed as an endowment from God that reflected an individual’s true character. Famous writers, politicians, actors, and athletes were approached—often besieged—by folks who came to be known as “autograph fiends.”

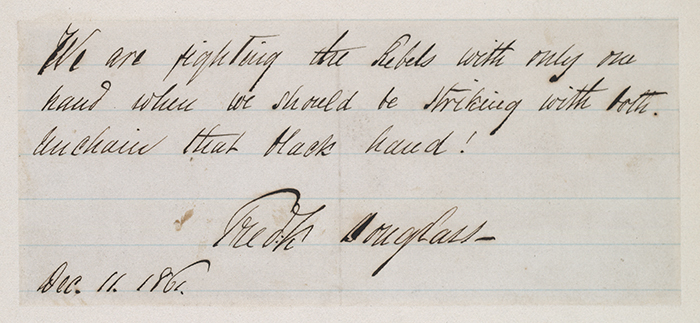

The Huntington has a number of items related to Douglass. Among them are two small cards with Douglass’s autographs. The first is a note dated Dec. 11, 1861. It reads: “We are fighting the Rebels with only one hand when we should be striking with both. Unchain that black hand!” The eloquent line sums up a central issue in the Union’s war efforts—the Militia Act of 1792 prevented Blacks from serving in the Union Army because it made military service available only to “free able-bodied white male citizens.”

The note, most likely a gift to an admirer, is a paraphrase from an article that appeared in the Sept. 1861 issue of a paper Douglass published about abolitionism, Douglass’ Monthly. The Union was “sorely pressed on every hand by a vast army of slaveholding rebels, flushed with success, and infuriated by the darkest inspirations of a deadly hate, bound to rule or ruin,” Douglass wrote. “Men in earnest don’t fight with one hand, when they might fight with two, and a man drowning would not refuse to be saved even by a colored hand.”

Note written and signed by Frederick Douglass, dated Dec. 11, 1861. It reads: “We are fighting the Rebels with only one hand when we should be striking with both. Unchain that black hand!” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

It took more than a year for Congress to amend the Militia Act. On July 17, 1862, the word “white” was dropped from the list of qualifications for enrollment: service became open to all “able bodied male citizens,” including “persons of African descent.” The Emancipation Proclamation specified that freed Confederate slaves could also be “received into the armed service of the United States.” By the end of the war, some 180,000 Black men had joined the United States Army.

As valuable collectibles, autographs were often auctioned off as part of fundraising campaigns. In the fall of 1863, a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by Lincoln fetched $3,000 at the Northwest Sanitary Fair, and the organizers forwarded the prize to the White House. In the summer of 1864, Lincoln signed copies of the Emancipation Proclamation that were auctioned off at a fundraiser for the Philadelphia Great Central Sanitary Fair.

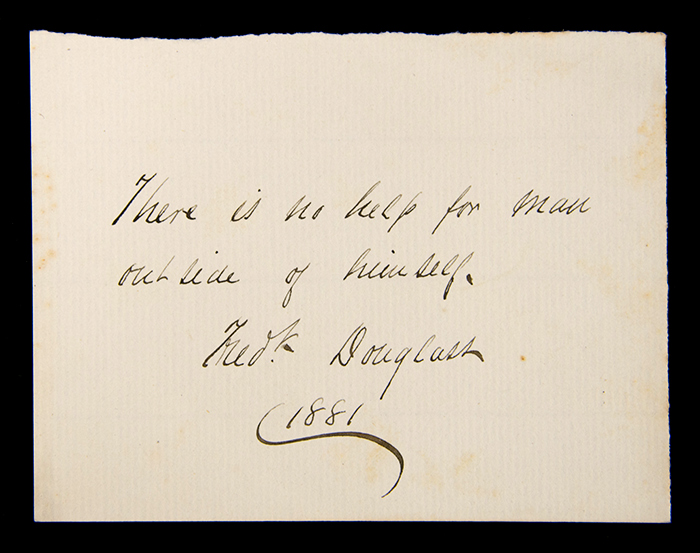

On Dec. 17, 1881, Frederick Douglass wrote a letter to Caroline M. Seymour Severance (1820–1914), a prominent abolitionist and suffragist. The letter included a “small contribution in aid of your effort in behalf of the Woman’s Hospital Fair.” The small contribution was an autograph of a paraphrase from his famous autobiography, just published in its latest edition. The card reads: “There is no help for man outside of himself.”

Douglass’s words—recorded in speeches, letters, newspapers, and books—cemented his legacy as a forceful voice against slavery and social injustice. But it is perhaps his eloquence that elevated those efforts to the level of celebrity.

An 1881 autograph of a paraphrase from Frederick Douglass’s famous autobiography, which had been recently published in its latest edition. Douglass included the autograph in a letter to Caroline M. Seymour Severance (1820–1914), a prominent abolitionist and suffragist. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.