The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Garden of Calligraphy

Posted on Wed., Sept. 29, 2021 by

Qianshen Bai, professor and dean of the School of Art and Archaeology at Zhejiang University, wrote the calligraphy on the title placard for the Chinese Garden’s new art gallery, Studio for Lodging the Mind. Bai spoke about the art of Chinese calligraphy on Sept. 9. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

Calligraphy is one of the oldest and most esteemed art forms in China. Its distinctive quality arises from its duality as both a visual art form and a means of written communication.

This becomes apparent in The Huntington’s exhibition “A Garden of Words: The Calligraphy of Liu Fang Yuan,” which shines a spotlight on the Chinese Garden’s calligraphy, fostering a deeper appreciation and understanding of the art. Featuring the work of 21 contemporary ink artists, “A Garden of Words” presents the variety and expressiveness of Chinese calligraphy in two installments: Part 1 is on view through Dec. 13, 2021, and Part 2 runs from Jan. 29 to May 16, 2022.

In conjunction with the exhibition, a series of lectures provides audiences with insights into different aspects of the art form.

The Huntington’s exhibition “A Garden of Words: The Calligraphy of Liu Fang Yuan” is designed to illuminate the art form and foster a deeper appreciation of its expressive qualities. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

On Sept. 9, the first lecturer, Qianshen Bai—professor and dean of the School of Art and Archaeology at Zhejiang University—shared his thoughts on the development and cultural significance of Chinese calligraphy. Bai’s own calligraphy is featured throughout the Chinese Garden, including the title placard for the garden’s new art gallery, the Studio for Lodging the Mind, where “A Garden of Words” is on view.

Bai began his lecture by asking, “What made writing the most treasured fine art in traditional China?” To answer this question, he explored the Chinese characters themselves, including their long history of evolution and the different scripts (think: font types) that have emerged over three millennia: seal, clerical, regular, running, and cursive.

Among various changes and transformations, the most significant one was the libian 隸變, the transformation from seal script to clerical script, which took place from the fourth century B.C. to the second century A.D. One of the earliest forms of Chinese writing, seal script features even lines, smooth curves, and a balanced, often symmetrical structure. Calligraphers usually need to manipulate the brush more slowly to achieve these effects. Clerical script, on the other hand, features broad, rectangular characters with wide, exuberant strokes. The script may have been developed by governmental scribes, who had to write large numbers of documents quickly.

For example, the character for “mountain” in seal script has a more complex structure: ![]()

In comparison, the clerical script character for the same word is easier to write: ![]()

“Communication efficiency was the dominant driving force behind the clerical transformation, and the aesthetic pursuit followed,” said Bai. “This period also witnessed the birth of the so-called cursive writing, a short-handed writing that is structurally simplified and executed with speed.”

As the artistic vocabulary of Chinese writing increased, so did the conscious pursuit to turn writing into art. The invention and improvement of paper, which has been produced in China since around 200 B.C., further contributed to the view of Chinese calligraphy as an art form.

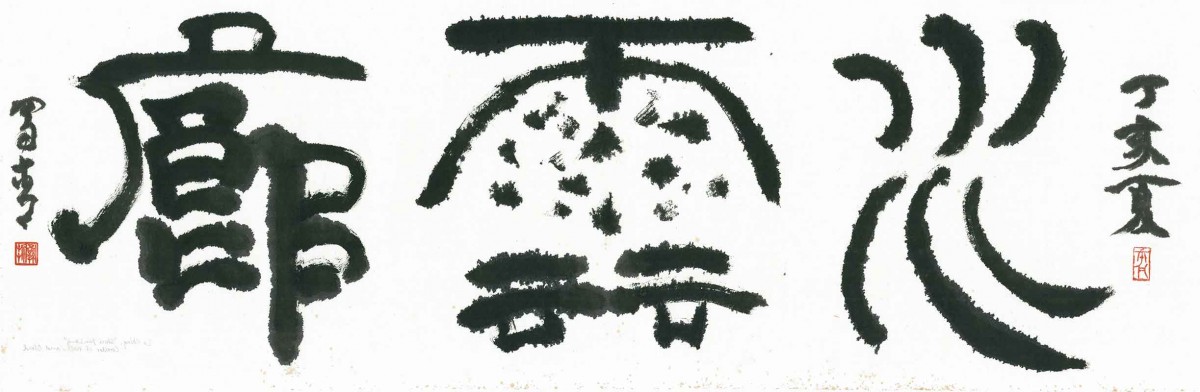

Lo Ch’ing 羅青 [Lo Ch’ing-che 羅青哲] (born 1948, Qingdao, Shandong Province, China; active Taiwan). Corridor of Water and Clouds 水雲廊, 2007. Handscroll, ink on paper; calligraphy written in seal script. Image: 16 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (42.5 x 92 cm); Mount: 16 x 52 in. (40.6 x 133 cm); Roller: 1 3/4 in. (4.5 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Bai noted that Pablo Picasso famously said, “If I were born Chinese, I would not be a painter but a writer. I’d write my pictures.”

As Chinese calligraphy was firmly established as a visual art among the educated elite, it became a specialized discipline, with masters, theoreticians, critics, and collectors.

However, because Chinese calligraphy has dual purposes, Bai presented a fundamental but unanswered question: Where lies the boundary between functional writing and visual art?

“For someone like me who has practiced calligraphy since youth and studied the history of calligraphy for more than 30 years,” he said, “I probably will never be able to find completely satisfactory answers.”

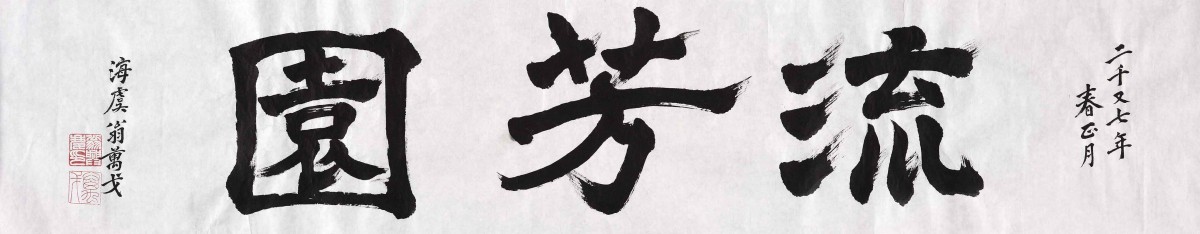

Wan-go H. C. Weng 翁萬戈 (1918–2020, born Shanghai; active United States). Garden of Flowing Fragrance 流芳園, 2007. Handscroll, ink on paper; calligraphy written in clerical script. Image: 10 3/8 x 50 7/8 in. (26.3 x 129 cm); Mount: 15 1/8 x 64 in. (38 x 162.5 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Long ago, before the advent of galleries and museums, letter writing was the main way to show off one’s calligraphy, and, as a result, it became not only a functional means of communication but also a conscious artistic pursuit. The earliest masterpieces of calligraphy were correspondence between individuals.

Because the tools employed for mundane writing and calligraphy were the same, it was difficult to distinguish between writings that were intentionally forms of art and those that were not.

“What makes things more complicated is that some leading literary figures and art critics even praised and promoted unintentional writings as better or even the best calligraphy,” said Bai.

This ambiguity highlights how the art of calligraphy—more than most other art forms—emphasizes the importance of immediacy, spontaneity, and unexpected outcomes.

“One of the reasons why people view some unintentional writings as masterpieces is a deeply rooted belief [that] calligraphy manifests one’s inner world,” said Bai. “It is traces of the mind.”

Watch Bai’s lecture, “Some Thoughts on the Art of Chinese Calligraphy.” The Center for East Asian Garden Studies’ previous lectures are also archived online.

The Huntington is hosting three more lectures about Chinese calligraphy, and the next one, “Wild Cursive Calligraphy, Poetry, and Buddhist Monks in the Eighth Century and Beyond,” will be held on Sept. 30. Calligraphy demonstrations will also be presented in the Chinese Garden, starting Oct. 16.

You can explore the Chinese Garden’s calligraphy here.

Cheryl Cheng is the senior editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.