The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Gasteria by Any Other Name

Posted on Tue., Aug. 16, 2022 by

Left: Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), Aloe Africana, Flore Rubro, undated, mid-18th century, opaque watercolor and pen and black ink on laid paper, 21 1/4 x 15 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Ehret’s drawing of Aloe Africana is rendered with tremendous attention to detail, which is why the image is curiously at odds with the features of the plant that is now designated Aloe africana. Right: An Aloe africana in The Huntington’s collection. Photo by John Trager.

The botanical art of Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) combines the romantic spirit of floral still life painting with the more utilitarian approach of herbals, books that recorded the uses and medicinal properties of plants. A prime example of the work that made him the most prominent botanical illustrator of his time, Aloe Africana, Flore Rubro is featured in “100 Great British Drawings,” on view through Sept. 5, 2022, in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery at The Huntington.

Ehret’s finely rendered drawing presents the whole plant in bloom, plus details of a single flower and its inner structure as well as the seed pod, whole and bisected. The Latin inscription below the image translates as “African Aloe, red flower, distinguished by whitish spots on both sides of the leaf.” And yet, for those familiar with these succulents, the plant depicted is clearly a Gasteria specimen, not an Aloe. This misidentification is particularly puzzling because the illustration is so beautifully detailed.

The succulent plant genus Gasteria was not established until 1809. The name was inspired by the slightly bulbous, stomach-like shape of the flowers. Photo by John Trager.

According to John Trager, the curator of the Desert Garden, “In the early days of Europeans working to describe the South African flora they encountered, ‘Aloe Africana’ was a bit of a catchall name for plants that bore similar features. So, this general description was a way of loosely grouping the plants until a consensus could be reached about their relatedness. Similarly, agaves were initially described as ‘Aloe Americana.’” Gasteria species were included in the genus Aloe until 1809, when French physician and botanist Henri August Duval proposed they be moved into the new genus Gasteria, named for the slightly bulbous, stomach-like shape of the flowers.

Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), Nectarines, undated, mid-18th century, watercolor and graphite on laid paper, 3 x 4 1/2 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Although Ehret’s drawing of nectarines does not adhere to documentary formatting, the attention to detail is typical of his scientific illustrations.

German-born Ehret had trained as a gardener but took up illustration at the age of 22. In 1736, he settled in England and began working at London’s Chelsea Physic Garden, which had been established in 1673 by apothecaries (community pharmacists) to grow medicinal plants. Isaac Rand, the director of the garden, encouraged Ehret to draw plants in the collection. Within the next 15 years, Ehret became one of Europe’s leading botanical illustrators, as well as a popular drawing instructor for aristocratic households, many of whom had established lavish gardens featuring unusual flora collected from around the globe.

Left: Mary Parker, Countess of Macclesfield (ca. 1761–1823), Venus’s Looking-Glass and Painted Lady Sweet Pea, undated, watercolor on parchment, 9 1/2 x 8 3/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Matilda Conyers (ca. 1698–1793), Wallflower and Tulip, 1767, watercolor and opaque watercolor over traces of graphite with brown ink (est. iron gall) inscriptions on vellum, 9 x 6 1/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Earlier this year, The Huntington acquired two albums of watercolor botanical drawings by Mary Parker, Countess of Macclesfield (ca. 1761–1823), and her daughter Lady Elizabeth Parker Fane (1751–1829), both students of Ehret. The illustrations, including this depiction of local flora, masterfully blend their artistic skill and deep botanical knowledge, marked by the unmistakable influence of their instructor. Matilda Conyers’ drawing of a wallflower and a tulip, featured in the exhibition “100 Great British Drawings,” shows the influence of Ehret, who may have been her instructor. An album with drawings by Conyers and her niece Henrietta Conyers also includes works by Ehret.

The 18th century was an era of political, scientific, and industrial revolution in Europe. It was also a period of exploration, colonization, and exploitation fueled by such powerful trading entities as the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Royal African Company, and the Dutch East India Company. The merchants who ran these organizations furthered their commercial interests by establishing trade routes that allowed them access to and control of commodities and raw materials that could not be produced domestically in Europe—notably spices, tea, tobacco, sugar, and cotton. These networks were also conduits for a bounty of biological specimens, including plants, that were of scientific interest. Before the advent of photography, recording a species new to the European observer meant closely examining and meticulously drawing the details by hand. Botanists relied on illustration and herbarium specimens (preserved plants) for documentation. Analyzing the plethora of plants being introduced from afar led to new systems for categorizing them. Ehret’s art was a vital part of that process.

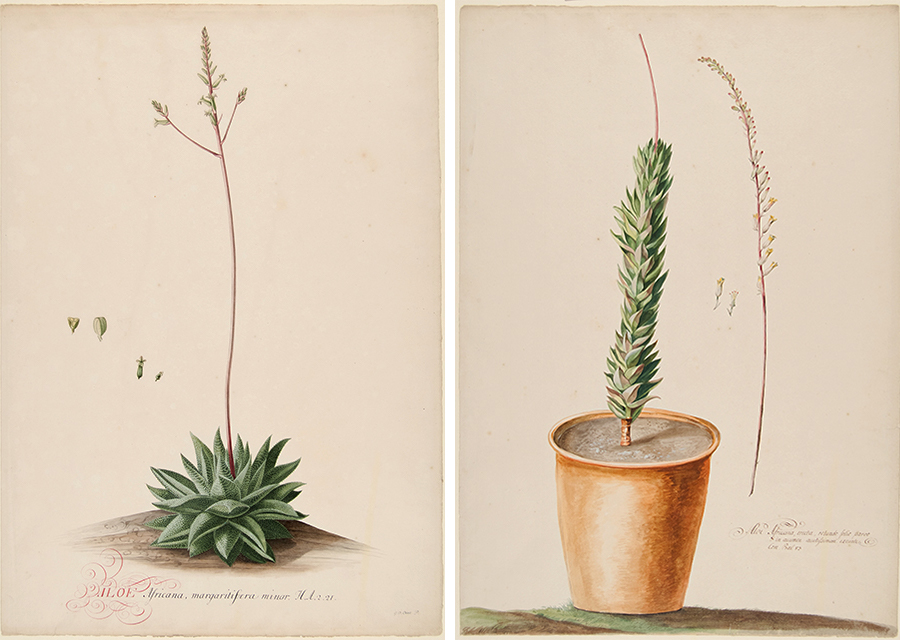

Left: Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), Aloe Africana, Margaritifea Minor, undated, watercolor on paper, 21 1/2 x 15 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), Aloe Africana, Erecta, Rotundo, undated, watercolor over traces of graphite on paper, annotation in pen and brown ink, 21 1/4 x 14 7/8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Plants that now belong to the genus Haworthia were also classified as Aloes in Ehret’s day. French physician and botanist Henri August Duval proposed the new genus in 1809 and named it in honor of British botanist and entomologist Adrian Hardy Haworth.

Among the books that Ehret illustrated was Hortus Cliffortianus (1738), commissioned by George Clifford, a banker and one of the directors of the Dutch East India Company. It was through this connection with Clifford that Ehret, in 1737, met the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who was the house physician and head gardener at Clifford’s estate. Linnaeus recognized Ehret’s artistic talent and eye for detail. From Linnaeus, Ehret learned to capture the morphological details of plants, particularly reproductive structures, which are the basis of botanical classification. Linnaeus’ Genera Plantarum (1737), featuring Ehret’s chart of the sexual anatomy inside flowers, was a precursor for Species Plantarum (1753), the first publication that consistently used the system of binomial nomenclature developed by Linnaeus. The system—in which a plant name is composed of two terms, the first indicating the genus and the second term indicating the species—is still used today.

The undated Aloe Africana, Flore Rubro is one of five Ehret drawings acquired by The Huntington in 1984. Part of a complete set of six believed to have been commissioned by wealthy British arts patron Ralph Willett, these five “Aloes” appear to replicate drawings that Ehret made in 1737 of succulent plants in the Chelsea Physic Garden collection. Each is labeled “Aloe Africana” followed by a descriptive phrase, a cumbersome convention that was common until the Linnaean system became the standard.

Gasteria disticha, the species depicted in Ehret’s Aloe Africana, Flore Rubro, is now common in cultivation and popular among succulent collectors. In parts of its natural southern African range, its existence is threatened by mining and agriculture. Photo by Tom Glavich.

Photography has replaced illustration as the primary method for recording new botanical discoveries, and the digital camera can capture a staggering amount of detail that is generally invisible to the human eye. Yet Ehret’s work remains fresh and relevant because he not only deftly documents his subjects’ distinguishing characteristics but also evokes the charismatic qualities that made them as appealing to his contemporaries as they are to botanists and plant enthusiasts today.

Sandy Masuo is the senior writer in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.