Posted on Thu., May 12, 2016 by

Thomas Moran, “Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” chromolithographic reproduction of a watercolor sketch as published in Ferdinand V. Hayden, The Yellowstone National Park, and the mountain regions of portions of Idaho, Nevada, Colorado and Utah. Boston, 1876. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When 19th-century trappers and explorers returned from the Yellowstone region of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, they told incredible tales of boiling mud, geysers, steaming rivers, and petrified trees. It would take the reports from several expeditions, including astonishing photographs and paintings, to confirm that these fantastical landscapes were indeed real.

Armed with this evidence, the U.S. Congress established Yellowstone as our first national park in 1872. Other parks, such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon, soon followed. By 1916, the U.S. Congress created the National Park Service to manage these national wonders.

To commemorate that centennial, The Huntington is mounting two related exhibitions in the Library’s West Hall. The first part, “Geographies of Wonder: Origin Stories of America’s National Parks, 1872–1933,” is on view May 14–Sept. 5, 2016. A second exhibition, “Geographies of Wonder: Evolution of the National Park Idea, 1933–2016,” goes on display Oct. 22, 2016–Feb. 13, 2017.

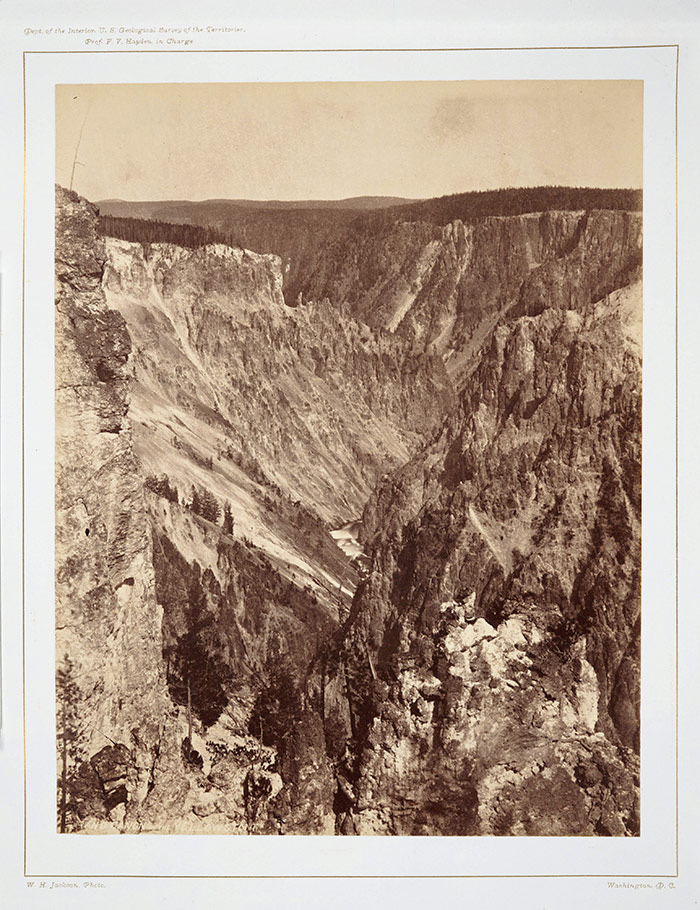

William Henry Jackson, vintage photograph of Yellowstone National Park’s Grand Canyon, from photo album of Yellowstone National Park and views in Montana and Wyoming territories, 1873. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The national parks are our nation’s crown jewels,” says Peter Blodgett, the H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington and exhibition curator. “This centennial gives us the opportunity to reflect a little more deeply on this remarkable system of public lands.”

The first exhibition, “Origin Stories of America’s National Parks,” features an 1873 album of large-format photos by William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), who participated in an 1871 expedition into Yellowstone and whose images played a role in its designation as a national park. Another artist present on the same trek as Jackson was the painter Thomas Moran (1837–1926), who created stunning watercolors of the landscape.

“Moran captured the incredible color,” says Blodgett, “and Jackson documented the detail of the area, putting to rest any doubts about the veracity of the landscape. The impact of these visuals was staggering.”

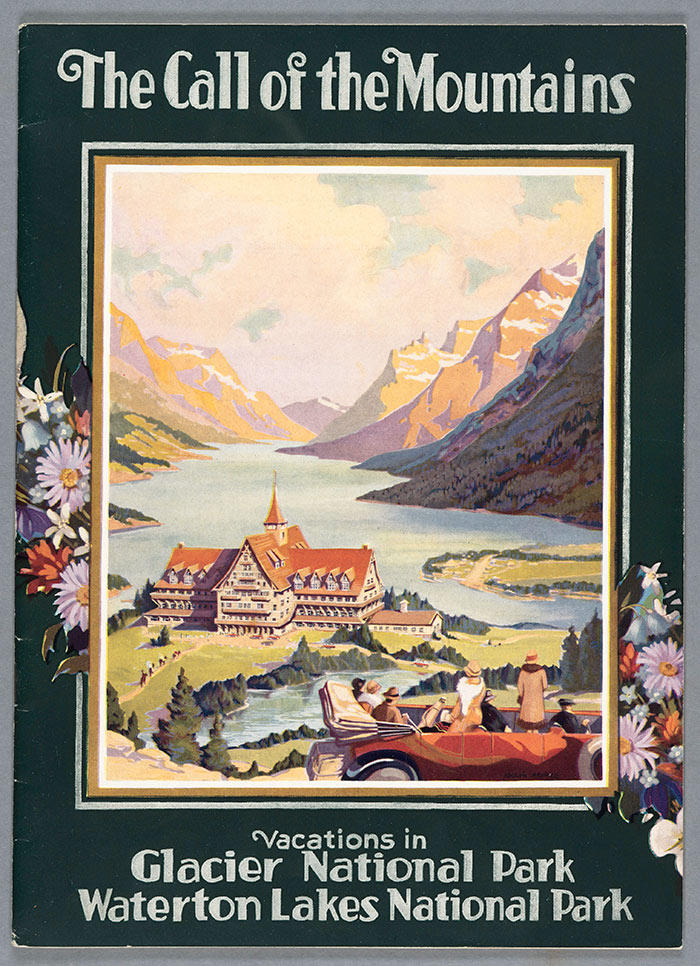

Great Northern Railway, cover of The Call of the Mountains, 1927. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Moran’s watercolors were turned into chromolithographs, the multicolor lithographs that were wildly popular in the era. Jackson’s photos were viewed on stereopticons, the “magic lanterns” of the 19th century, and transformed into engravings published in such mass-market magazines as Scribner’s and The Century. Images showing Yellowstone and other national parks fueled a growing tourism industry.

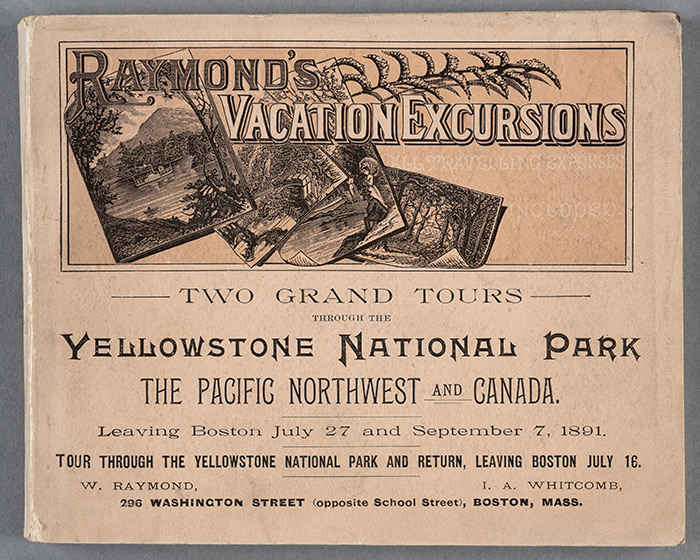

A diary on display in the exhibition shows one young woman’s fascination with Yosemite, which became a national park in 1890. Amy Bridges booked an excursion with the Raymond-Whitcomb Company, travelling from Boston to the Pacific Coast. She writes glowingly that she had finally fulfilled “one of the greatest desires of my life, a trip to the Yosemite Valley.”

Other items from The Huntington’s collections include brochures, posters, and guidebooks that demonstrate the role of private enterprise in the parks’ development. Documents show how the Northern Pacific Railroad, which early on recognized the importance of rail service to Yellowstone, pushed for the early protection of the park. The railroad also advertised the rugged mountains and spectacular lakes of Glacier National Park in its poster titled The Call of the Mountains.

Raymond-Whitcomb Co., guide book cover, “Two Grand Tours Through the Yellowstone National Park,” 1891. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The establishment of the national park system was not without controversy, which the exhibition also explores. One conflict that continues to this day is the decision to flood the Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park. The main reason for this act was to increase the water supply to San Francisco, a critical need demonstrated by the devastating fires that followed the 1906 earthquake.

Yet conservationists countered that the Hetch Hetchy Valley rivaled the Yosemite Valley in beauty and that erecting a dam within the boundaries of a national park would compromise the very existence of the park.

These opposing views attest to the significance of the National Park Service. As it has in the past, the National Park Service continues to help balance competing priorities. On the one hand are the rights of a nation to tap its resources for the needs of its citizens. On the other is the desire to preserve the pristine landscapes that are hallmarks of that same nation’s identity.

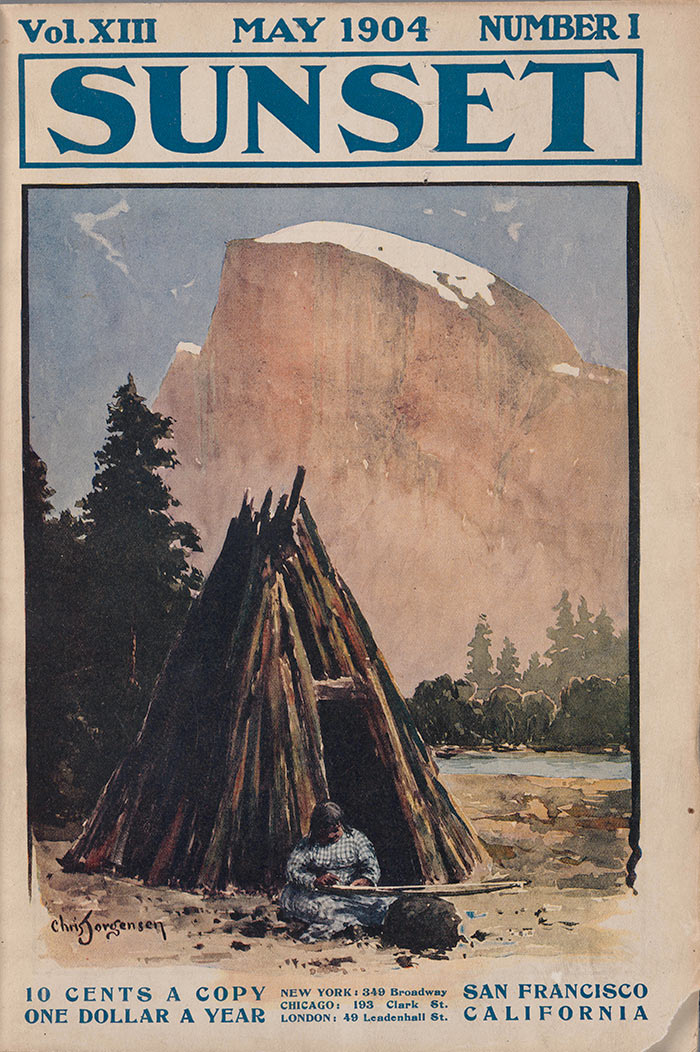

Sunset magazine, May 1904 issue cover, painted by Chris Jorgensen. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing.