The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Henry Moore on Paper

Posted on Wed., June 13, 2018 by

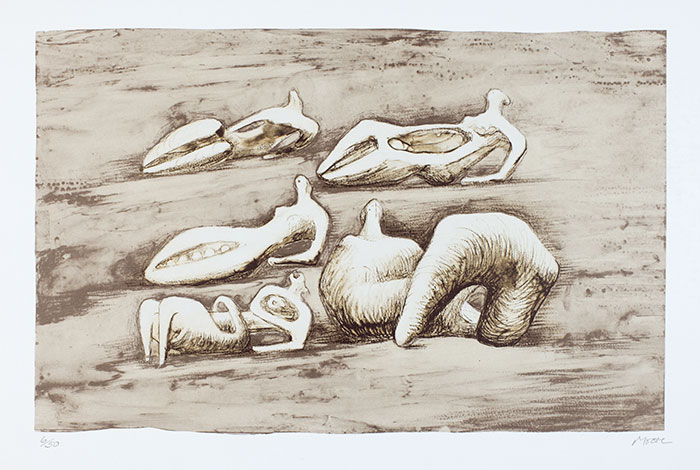

Henry Moore, Five Reclining Figures, 1979, lithograph, 19 x 25 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation. © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS 2017 / henry-moore.org.

Can a piece of sculpture and a print on paper have the same effect? The differences between them seem clear. One is plastic; the other, graphic. One exists in three dimensions; the other, in only two. However, with an artist like Henry Moore (1898–1986), it is sometimes difficult to draw the line between the two mediums.

Moore is Britain’s best-known modernist sculptor. His monumental, biomorphic forms and figures that decorate public spaces and museum collections worldwide are easily recognized by most. But, as the exhibition Spirit and Essence, Line and Form: The Graphic Work of Henry Moore makes clear, Moore was also a master printmaker. The exhibition presents a small selection of works drawn from the Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation’s recent gift of more than 330 prints by Moore—works that reveal how the artist often blurred the boundaries between his sculpted and printed work.

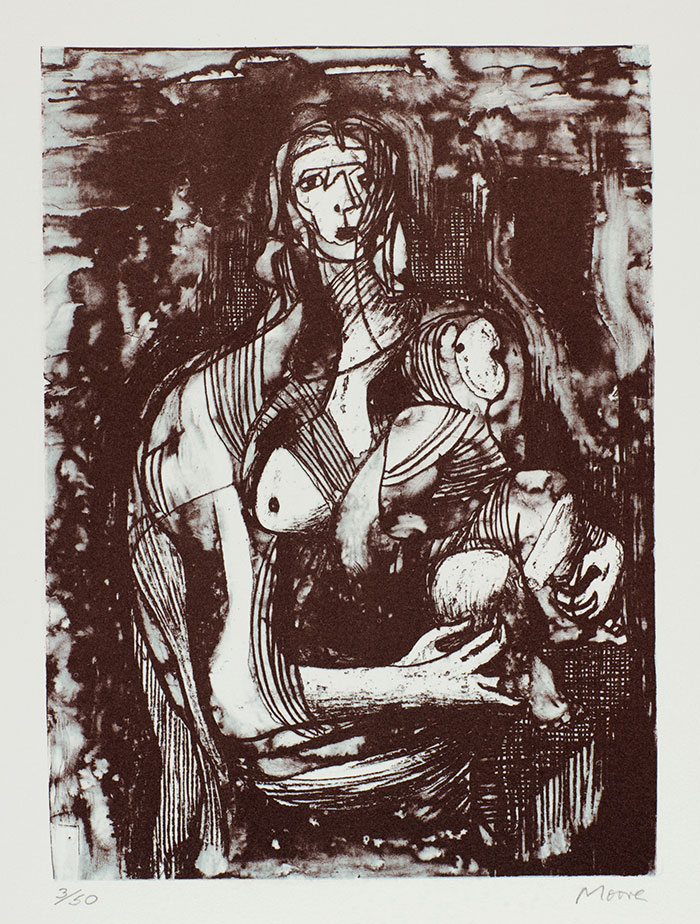

Henry Moore, Mother and Child, 1973, lithograph, 20 x 15 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation. © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS 2017 / henry-moore.org.

Moore’s graphic art presents many of the same themes and subjects found in his sculptures. One of these is the reclining figure, a motif repeated in the lithograph Five Reclining Figures (1979). Though these forms, often female, may recall universal themes, such as fertility or the roots of creation, the reclining figure also provided Moore with a way to experiment with form and shape, and to try out ideas. In Five Reclining Figures, the sculpture-like forms twist and bend around themselves. Some appear almost as hard and solid as boulders. Others are soft, living shapes. Has one opened her belly to reveal a baby inside?

Another recurring theme found in Moore’s work is the mother and child. He called it “one of my two or three obsessions.” As with his reclining figures, the mother and child offer the artist seemingly endless possibilities for variation. One example on view in the exhibition is a lithograph from 1973. Mother and Child, with its frontal, half-length format recalls the sober image of a Renaissance painting of the Virgin and Child or the stillness of a Byzantine icon. As if sculpted, the figures sit solid before us while the print’s writhing lines and flattened planes play with the possibilities of two dimensions.

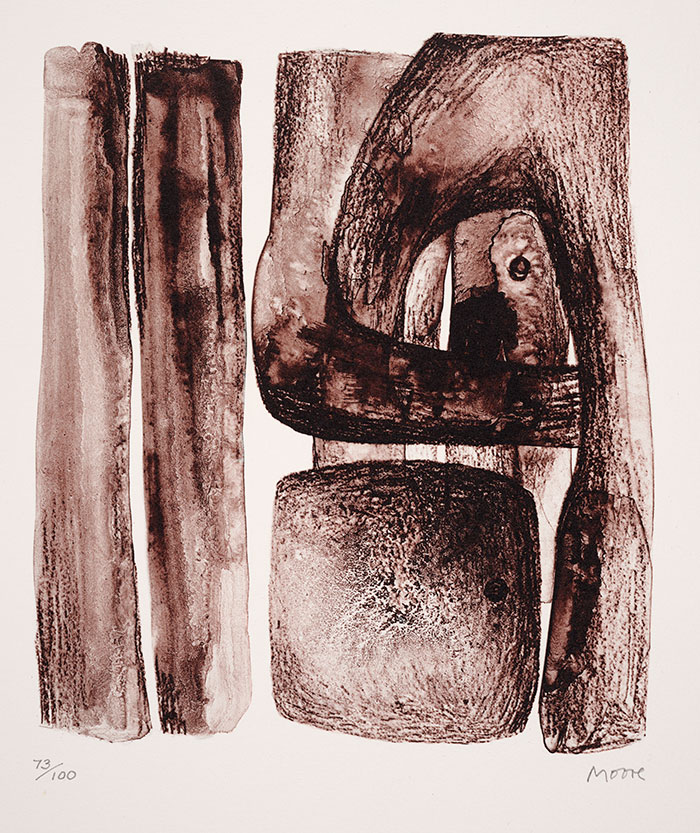

Henry Moore, Mexican Mask, 1974, lithograph, 26 x 19 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation. © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS 2017 / henry-moore.org.

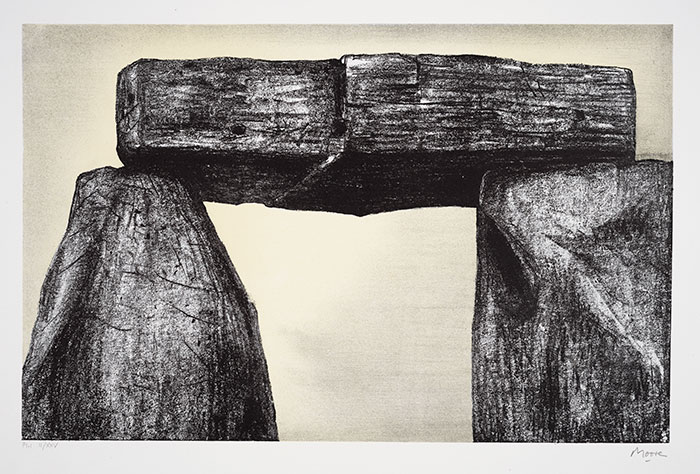

Moore often took actual sculptural works as inspiration for his prints. His image of a Mexican Mask (1974) recalls the kind of Mesoamerican sculpture that inspired him early in his career. With its solid, textured curves and receding voids, the image appears three-dimensional, as if we could reach out and touch a surface of carved stone rather than paper. In another print, a lithograph of one of Stonehenge’s great monoliths lends the prehistoric structure a sense of mystery. The composition, a close-up and only partial view, appears unable to capture the whole monument, enhancing the feeling of awe that Moore felt when, as a young man, he first visited the ancient site.

These prints and more will be on view in the Chandler Gallery of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art from June 16 through October 1.

Melinda McCurdy is associate curator of British art at The Huntington.

Henry Moore, Stonehenge I, 1973, lithograph, 23 x 18 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Philip and Muriel Berman Foundation. © The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS 2017 / henry-moore.org.