The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

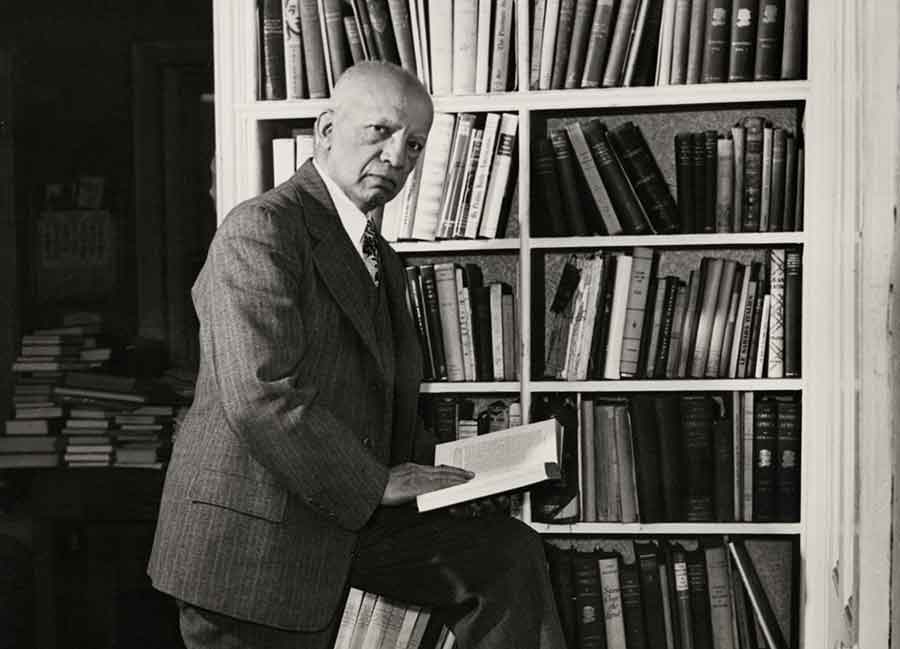

Historian Carter G. Woodson

Posted on Wed., Feb. 27, 2019 by

Carter G. Woodson in his library. Photo courtesy of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Known today as the "Father of Black History," Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950) was one of the first Black historians to begin writing about Black culture and experience—and the second to earn a doctorate at Harvard University (W. E. B. Du Bois was the first).

As a young child, Woodson spent much of his time working on his family’s farm in Virginia, and as a teenager, he worked as an agricultural day laborer. But in 1895, he enrolled in Frederick Douglass High School in Huntington, West Virginia, completing four years of coursework in just two years. From there, he continued his education in Kentucky, at Berea College, a school founded by abolitionists, and went on to receive his master’s degree in European history in 1907 from the University of Chicago. Five years later, Woodson would earn his Ph.D. in history at Harvard University, writing his dissertation on the state of West Virginia after the Civil War broke out, titled “The Disruption of Virginia.”

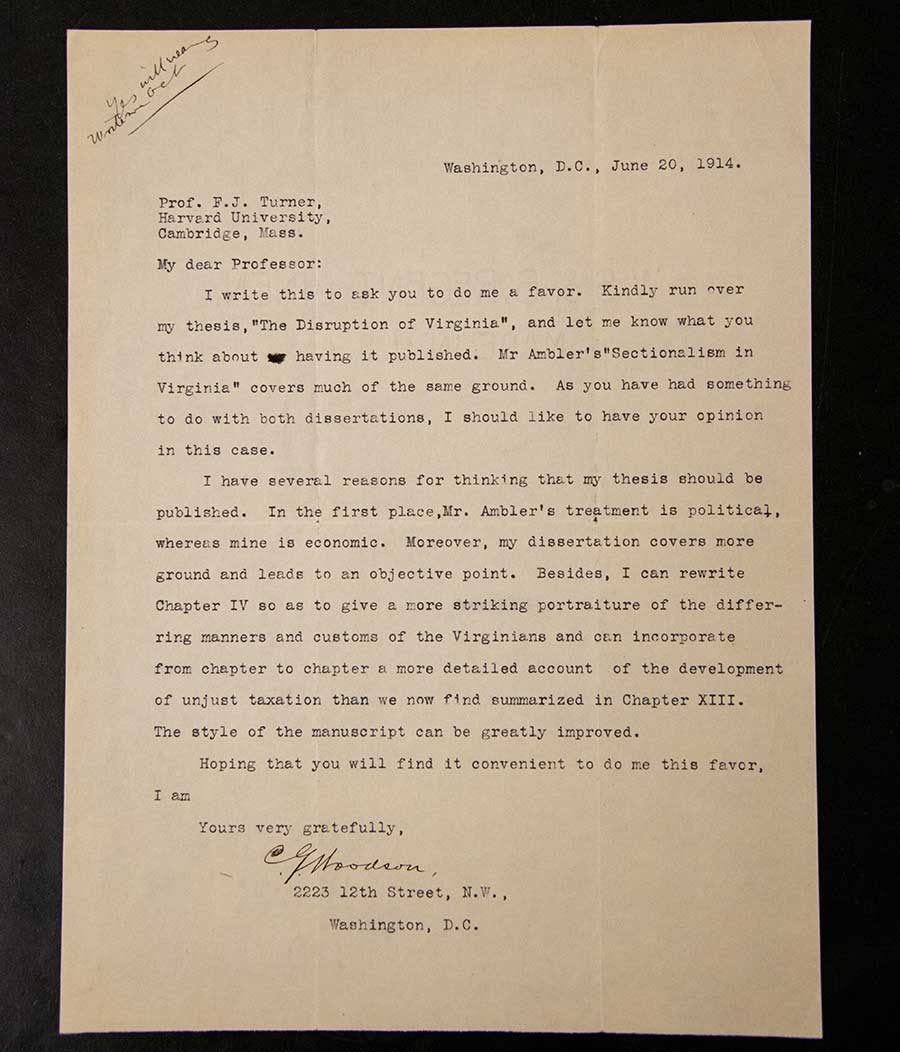

Carter G. Woodson, typewritten letter to historian Frederick Jackson Turner regarding the publication of his dissertation, June 20, 1914. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In The Huntington's library collection, there is a letter from Woodson to one of his Harvard professors, famed historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861–1932). (Turner joined The Huntington as a research associate in 1927, and his papers were acquired by The Huntington after his death in 1932.) In his letter to Turner, Woodson acknowledges that others have written about Virginia's history but not from his perspective: "I have several reasons for thinking that my thesis should be published. In the first place, Mr. Ambler's treatment is political, whereas mine is economic. Moreover, my dissertation covers more ground and leads to an objective point."

Assistant Curator of Literary Collections Natalie Russell emphasizes the importance of this letter: "It's fascinating to think about the perspective Woodson must have brought to his subject. Knowing that he later championed the study of Black history as a method of stimulating racial pride and improving race relations, and that contemporary historians often viewed Blacks in the role of victim, what agency and economic power exercised by African Americans might he have argued? What historic 'truths' might he have challenged? Perhaps his view was too radical for publishers at the time."

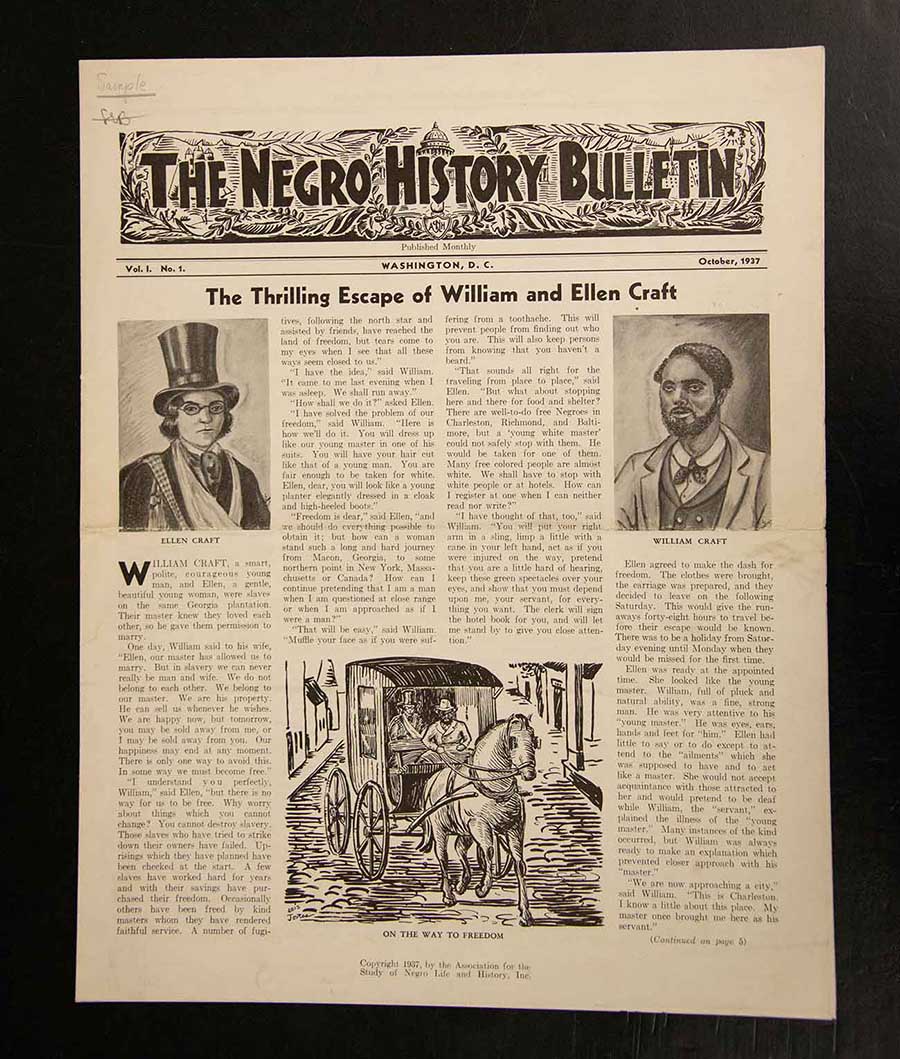

The first edition of The Negro History Bulletin, edited by Carter G. Woodson, published in October 1937 through the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

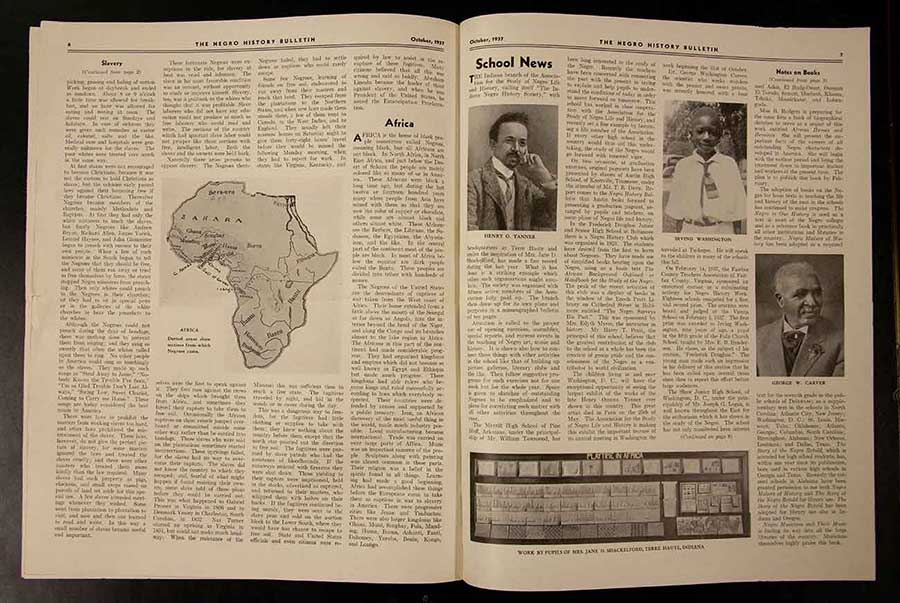

Woodson never did get his dissertation published, but he went on to establish the Journal of Negro History in 1916 and The Negro History Bulletin in 1937. These publications provided venues for Black scholars to publish their research and platforms for stories celebrating Black history and culture. Peter Blodgett, H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western American History, explains the importance of Woodson’s actions at that point in history. “Consider the fact that, in 1915, the motion picture Birth of a Nation was released, a film that portrayed the Ku Klux Klan of the 1870s in a heroic light and that inspired the rebirth of the Klan in 1915. Furthermore, it was a time when very few universities admitted African Americans as candidates for advanced degrees in such subjects as American history. Only in the decades following World War II would a new generation of Black scholars, such as John Hope Franklin and others, begin to reach a national audience.”

A look inside the first edition of The Negro History Bulletin, edited by Carter G. Woodson, published in October 1937 through the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of Woodson’s lasting legacies is the creation of “Negro History Week.” Originally, Woodson established the celebration during the second week of February, which included the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Woodson’s goal was to call national attention to the stories of Black Americans and encourage cultural pride. Near the end of his life, Negro History Week was formally celebrated in every state and also in several other countries. By 1969, educators put forth the first proposal to extend the celebration to a month, and, in 1976, President Gerald Ford formally designated February as Black History Month.

Deborah Miller is social media manager in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.