The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The History of Los Angeles as a Transnational Region

Posted on Mon., June 13, 2011 by

William Deverell, the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, chats with USC doctoral student Jessica Kim about her research. This is part of a series highlighting the work of USC graduate students.

WD: In brief, what's your dissertation about?

JK: I'm interested in thinking historically about the ways in which the city of Los Angeles became linked to the rest of the world at the beginning of the 20th century. I see early 20th-century Los Angeles as a "global city-region," or a metropolitan area that extended past the boundaries of the United States and stretched into northern Mexico. In my dissertation, I hope to show that international commerce and investment bound Southern California and northern Mexico into a closely connected, transnational region in the early part of the 20th century. I also examine how the Mexican Revolution challenged the economic links between Southern California and northern Mexico and redefined the relationship between the two nations by the 1930s.

WD: What do we already know about this topic?

JK: We know a lot about the history of Los Angeles in terms of race, ethnicity, and immigration. We also know quite a bit about links between contemporary Los Angeles and the rest of the world. In recent years, an "LA school" has even emerged, characterizing Los Angeles as the prototype of a new type of urbanism—sprawling, incredibly diverse, and with an extraordinary divide between the rich and the poor.

WD: What don't we know that you are going to tell us?

JK: Despite an important and growing body of scholarly literature on the history of Los Angeles, we know very little about Los Angeles' links to the rest of the world before World War II. I see my project as a first step in making L.A. history transnational in the first half of the 20th century.

WD: Where do you do your research?

JK: I've been all over Los Angeles and Southern California—from San Diego to Laguna Niguel to Pasadena. The project is also taking me to Mexico. I'll be working in the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City for six weeks this summer as well as in local archives in Baja California, Sinaloa, Nayarit, and Sonora.

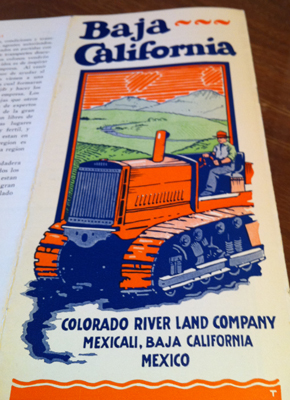

A promotional brochure for the Colorado River Land Company, a 1 million acre ranch in Baja California owned by a number of prominent Angelenos, including Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler, publishers of the Los Angeles Times.

WD: Who are your role models in terms of figuring out about the West?

JK: Patricia Limerick, for her engaging style and for bringing histories of race, ethnicity, and immigration into conversation with Western historiography. And young borderlands scholars like Gerardo Cadava, Rachel St. John, and Sam Truett for revitalizing the history of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

WD: What is the hardest part about doing this work?

JK: Historical research is like trying to solve a mystery with a lot of clues and sources that don't always lead you where you expect them to. I'll enter an archive looking for something I hope might clearly solve my historical puzzle. Instead, I'll come across something surprising that leads my project in a completely unexpected direction. This process is complicated, but it keeps my project dynamic and accountable to my sources.

WD: What's the best part of doing this kind of research?

JK: It's related to the hardest part—surprises. Uncovering something unexpected in an archive is an incredibly exciting experience. Historical actors constantly astonish and amaze historians. Living in the 21st century, we can never really predict what we will find in an archive. The people we research are unpredictable—they often thought and acted in ways that seem unfathomable to those of us living now. Rediscovering what they did and what compelled them to do it is a fascinating endeavor.

WD: What is the most unusual thing you've discovered in your research?

JK: While researching how Angelenos reacted to the violence of the Mexican Revolution, unfolding just a few hundred miles south of their city, I discovered that they appealed to the federal government to intervene in Mexico in an unusual and gruesome way. Dozens of Angelenos lived in Mexico, many on ranches they had purchased as investment properties. They became the targets of Mexican revolutionaries who opposed foreign investment. To raise money for their cause, Mexican revolutionaries kidnapped and held at least six Angelenos captive for ransom. To motivate Angeleno families to pay up, revolutionary forces sent severed fingers north across the border. Enraged, Angelenos prepared a dossier of evidence to appeal for congress to intervene in Mexico. The dossier included the severed fingers of Los Angeles residents Gustavus Whiteford and Otto Land preserved in a bottle of alcohol. I've often wondered what happened to that collection of evidence.

Jessica Kim's dissertation is titled "Metropolis, Empire, and Revolution in the Los Angeles-Mexico Borderlands, 1890–1930" and will be completed in the spring of 2012. She has received fellowships from the Huntington Library, the USC-Huntington Institute on California and the West, and the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations.

William Deverell is the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW).