The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Hollywood Master Remembered

Posted on Tue., May 26, 2015 by

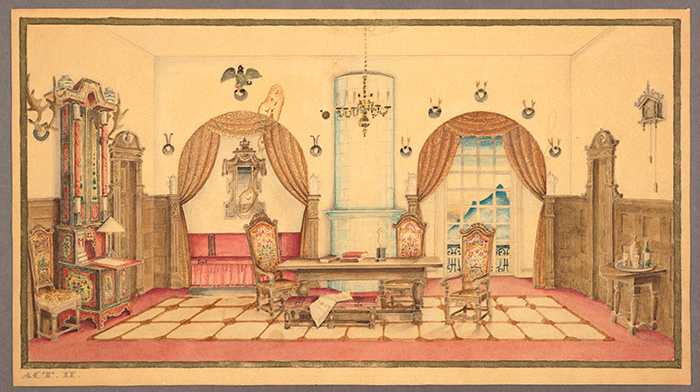

In this watercolor, ca. 1935, Kay Rasmus Nielsen (1886-1957) depicts a Swiss hotel room for Act 2 of Zoë Akins’ play The Human Element. Art critics saw the influence of English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) in Nielsen’s work, along with elements of Chinese art and the Art Nouveau movement. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For Americans looking for respite from the Great Depression and later World War II, the entertainment industry provided welcome relief. Los Angeles in the 1930s and 40s was a hotbed of film and theater production, attracting a great number of actors, screenwriters, filmmakers, and other artists to help satisfy the demand. Danish illustrator Kay Rasmus Nielsen (Kay rhymes with “eye”) was one such artist, traveling to California to work on a stage production of Everyman at the Hollywood Bowl in 1936.

Few people today recognize Nielsen’s name. He gained renown in Europe in the early part of the 20th century during the Golden Age of Illustration, when advances in technology had made it possible to reproduce drawings and paintings accurately. His exquisite illustrations are ethereal and fantastic, with fine detail and a sophisticated use of color and shading. Nielsen is best known for his children’s book illustrations, and particularly for his depictions of fairy tales, such as East of the Sun, West of the Moon (1914) and Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales (1924).

Nielsen, a scion of a theater family, brought his talents to Los Angeles during Hollywood’s heyday, settling in Altadena and finding work with a number of clients, including the Walt Disney Company. The Huntington has several original illustrations by Nielsen in the archive of Hollywood screenwriter Zoë Akins, the bulk of whose papers arrived here in 1952. Akins was an accomplished playwright, poet, and author who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1935 for her stage adaptation of Edith Wharton’s novella The Old Maid and went on to write films starring Claudette Colbert and Greta Garbo, among others. She and Nielsen met sometime in the late 1930s and remained friends for life.

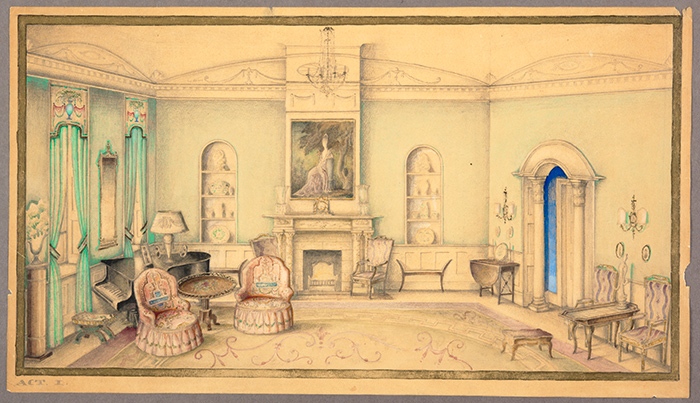

Kay Rasmus Nielsen, set design for Act 1 of Akins’ The Human Element, the Duke of St. Erth’s house in London, watercolor, ca. 1935. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The highlight of The Huntington’s Nielsen holdings is a set of watercolor illustrations for stage sets, produced in preparation for Akins’ stage adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s 1930 short story The Human Element. Charting the foibles of the human heart, The Human Element tells the tale of a socialite (the daughter of an English duke) and her admirers, and reveals a secret love between the daughter and a household servant.

Nielsen’s watercolors possess a dreamy quality, evoking both resplendence and intimacy. The first act takes place in the duke’s house in London. Nielsen’s treatment of the scene shows finely wrought detail and delicate hues that suffuse the furnishings and décor with soft afternoon light. From correspondence in the collection, we know that Nielsen and Akins worked closely to match the arrangement of the furniture to the action.

The second act takes place in a hotel in Switzerland. Nielsen’s design makes clear the resort locale, equipping the room with antlers, steins, a cuckoo clock, and distant mountain peaks that appear in the single window. His meticulous brushwork crafts the embroidery on the chairs, the scroll patterns on the curtain, and carved accents on the wood paneling.

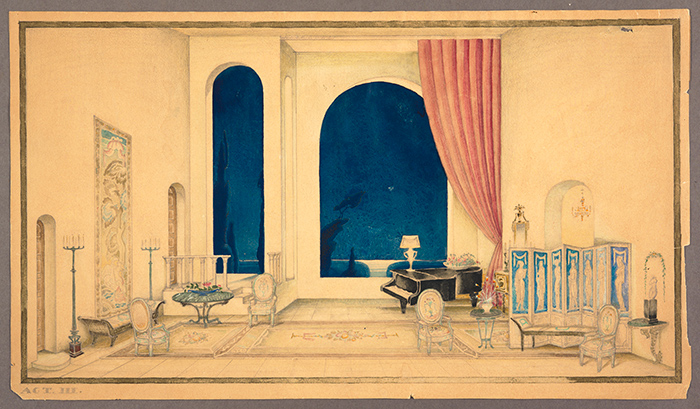

Kay Rasmus Nielsen, set design for Act 3 of Akins’ The Human Element, The Isle of Rhodes, watercolor, ca. 1935. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the third act, the full truth of the lovers’ scandal is revealed. Akins wrote that she wanted to retain the “ominous quality” of a nighttime scene. Nielsen’s stunning illustration captures this feeling beautifully. A midnight-blue darkness fills the windows that open toward the largely unseen exotic location beyond the stage, the Greek island of Rhodes.

Clippings and letters discuss a planned opening of The Human Element, possibly at New York’s Empire Theatre, but sadly the production never got off the ground. It was the first of many disappointments for Nielsen.

After World War II, the art world embraced naturalism and realism, and Nielsen’s fantasy style fell out of favor. As a result, Nielsen found less and less work in any medium, although friends did help him gain a few commissions for murals in Los Angeles. He also remained in touch with Akins, asking her in 1954 to help him explain one of his murals: “Poet—do write something for me explaining my idea of the picture in your way . . . what I [wrote] is so hopelessly awful.” Despite receiving the occasional commission, Nielsen was penniless when he passed away in 1957.

A photograph of Kay Rasmus Nielsen, around the time he designed the sets for The Human Element. Photographer unknown. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In later decades, Nielsen’s work experienced something of a renaissance. The Unknown Paintings of Kay Nielsen, published in 1977, garnered acclaim for a series of previously unpublished illustrations of the Arabian Nights. Then, in the 1980s, the Walt Disney Company uncovered some concept sketches Nielsen had produced for an adaptation of fellow countryman Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. The designs had languished for years. When rediscovered, they so inspired modern animators that Nielsen received screen credit in the 1989 blockbuster animated film.

Original designs and books by Nielsen are now considered valuable examples of the Golden Age of Illustration. The Huntington is pleased to preserve a part of this legacy in a few delightful examples by an underappreciated master.

Natalie Russell is assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington.