The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

An Ingeniously Printed Book of Songs

Posted on Thu., March 16, 2017 by

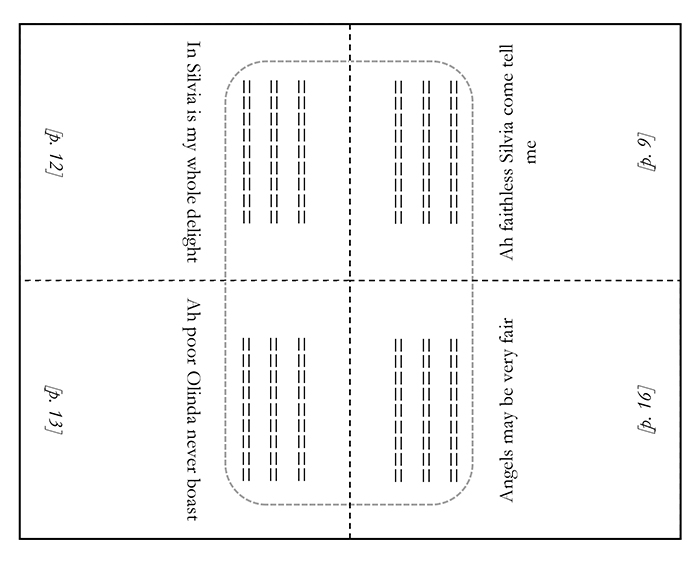

![A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (London, 1685). Two-page opening (pages [12]–[13]) showing two songs: “In Silvia is my whole delight” (anonymous and unique) and “Ah poor Olinda never boast” (music by Robert King and text by “a Lady,” from the play A Duke and No Duke by Nahum Tate). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/uploads/2017/01/songbook-1.jpg)

A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (London, 1685). Two-page opening (pages [12]–[13]) showing two songs: “In Silvia is my whole delight” (anonymous and unique) and “Ah poor Olinda never boast” (music by Robert King and text by “a Lady,” from the play A Duke and No Duke by Nahum Tate). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Examining a real book up close can tell us things that a microfilmed or black-and-white online image of the object doesn’t show. Scholars often discover interesting information by inspecting a book’s watermarks, paper stocks, or bindings.

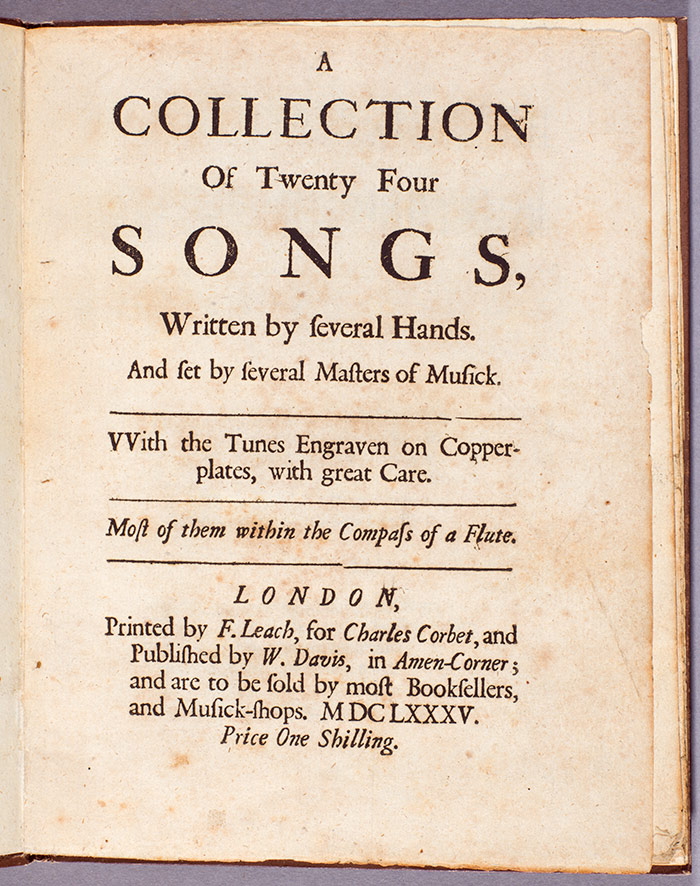

A good example of this is a fascinating booklet dating from 1685 called A Collection of Twenty Four Songs, Written by Several Hands. And Set by Several Masters of Musick, of which The Huntington possesses the only known copy. This odd little compilation was published in London under the auspices of a slightly shady character known as Charles Corbet. The whole affair is rather slapdash. The compiler doesn’t provide page numbers or identify composers and supplies only the songs’ melody lines (a real problem in the case of four songs that cannot be found elsewhere). There are also numerous mistakes in both the text and the musical notation.

Even so, A Collection of Twenty Four Songs is intriguing because it combines two printing methods on each page. The texts of the songs were created using moveable type, and the music was produced by means of copperplate engraving. In the former procedure, individual pieces of metal type—each carrying a raised letter, punctuation mark, or blank space—were cinched together into a frame and placed in a printing press, where they were inked and then applied by means of a lever onto each sheet of paper.

![A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (London, 1685). Detail of page [12], showing the impression (“bite”) left by the copper plate used to print the musical notes. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/uploads/2017/01/songbook-3.jpg)

A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (London, 1685). Detail of page [12], showing the impression (“bite”) left by the copper plate used to print the musical notes. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the other method, a smooth, thin plate of copper was engraved with tiny grooves—in this case for the musical notation—and then the grooves were filled with ink (the rest of the plate being wiped clean). Finally, the plate and a piece of paper were pressed together and rolled through an “intaglio” press (something like an old-fashioned clothes wringer), forcing the ink from the grooves onto the paper.

It is clear that in the case of A Collection of Twenty Four Songs, each sheet of paper had to undergo both processes before the printed page was complete. But mastering the actual printing technologies was only the first step. Then the printer needed to assemble the book. With engraved printing, this was a relatively easy process: single pages of a book were engraved and printed individually—often using only one side of the sheet of paper and leaving the other side blank—and were then bound together, just as you might send a document from your computer to your printer and then have the single-sided pages spiral-bound at your local copy center.

Books produced with moveable type were generally much more complex, being built up through multiple-page “gatherings.” Four pages were set up and printed together, top-to-top and side-to-side, on one side of a large sheet of paper; then another four pages were printed on the other side of the sheet. The sheet was then folded in half, and in half again, and finally the connected tops were slit open, and presto—the printer had an eight-page gathering that, when stitched together with other such gatherings, formed a book.

Andrew Walkling’s schematic mockup showing how one side of sheet B of A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (the “outer forme”) was laid out for printing. After being printed on the other side as well, the sheet would have been folded twice, slit open along the top, and bound as part of the completed book.

You can try this at home. Fold any piece of paper in half and half again, then holding it like a book, number the pages from one to eight. Then unfold it to check the configuration of your pages and note which page numbers are right-side up or upside down. I do it all the time with my students.

So how did Corbet bring these two very different processes together in our curious little music book? Once I came to The Huntington and had a chance to inspect the volume in person, I discovered a clue that the microfilmed image of it didn’t show: it was a mark laid down by the edges of the copper plate as it “bit” into the paper when plate and paper were crushed together in the intaglio press.

This mark spans each two-page spread and crosses over the tops of the pages, revealing Corbet’s ingenious solution. He would first print four pages of moveable-type text onto a large sheet of paper—laying them top-to-top and side-to-side—and leave a blank space in the center for the music. Then he created the musical notation on copper plates, assembling four tunes on each plate laid in the same configuration. He would run the whole sheet through the intaglio press to add the music, repeating the same two-part process for the sheet’s other side. Then he’d fold it to create each eight-page, eight-song gathering.

Corbet’s approach may have been a product of necessity. He didn’t have access to the typefaces that London’s specialized music publishers used, and producing a full-blown engraved edition of songs would have proved too expensive for his middle-class customers. His imaginative half-and-half approach has its own compelling logic. Sadly, it did Corbet little good. Shortly after the publication of this unusual music book, he disappeared from the historical record without a trace.

A Collection of Twenty Four Songs (London, 1685). Title page. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Andrew R. Walkling is associate professor of Early Modern Studies at Binghamton University and was a short-term Andrew W. Mellon Foundation fellow at The Huntington.