The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Interpreting the Music of Harold Bruce Forsythe

Posted on Wed., Aug. 5, 2020 by

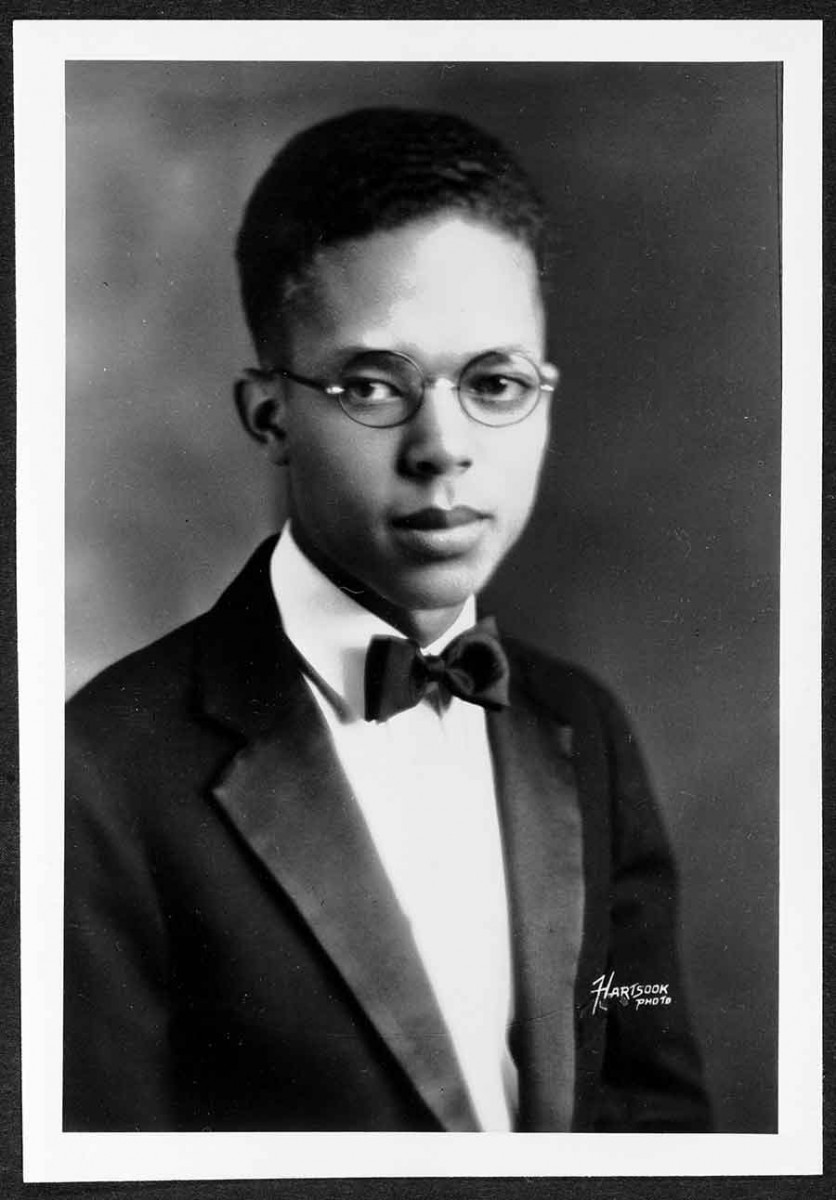

Composer and writer Harold Bruce Forsythe (1908–1976). Photo by Fred Hartsook. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Most researchers using our literary collections at The Huntington are writing biographies or academic articles. But we also work with publishers and artists who want to bring new audiences to the creators in our collections. And those are not two separate categories. We work with many educators who are themselves also artists and performers, and eager to explore the relevance of earlier artists, even obscure ones, in their work and with their students.

One of the less well-known names in our collection is that of writer and composer Harold Bruce Forsythe, whose papers were donated to The Huntington by his son following Forsythe’s death in 1976. Few today know Forsythe’s name, much less his work, but it is possible that his musical compositions will be more well known in the years to come than they were during his own lifetime.

Born in 1908, Forsythe showed musical aptitude early in life. After attending Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, he was awarded a fellowship to study classical piano and composition at the Juilliard Graduate School in New York City. During his time at Juilliard, a hearing impairment emerged that interrupted his studies and forced him to abandon a career as a musician by 1940.

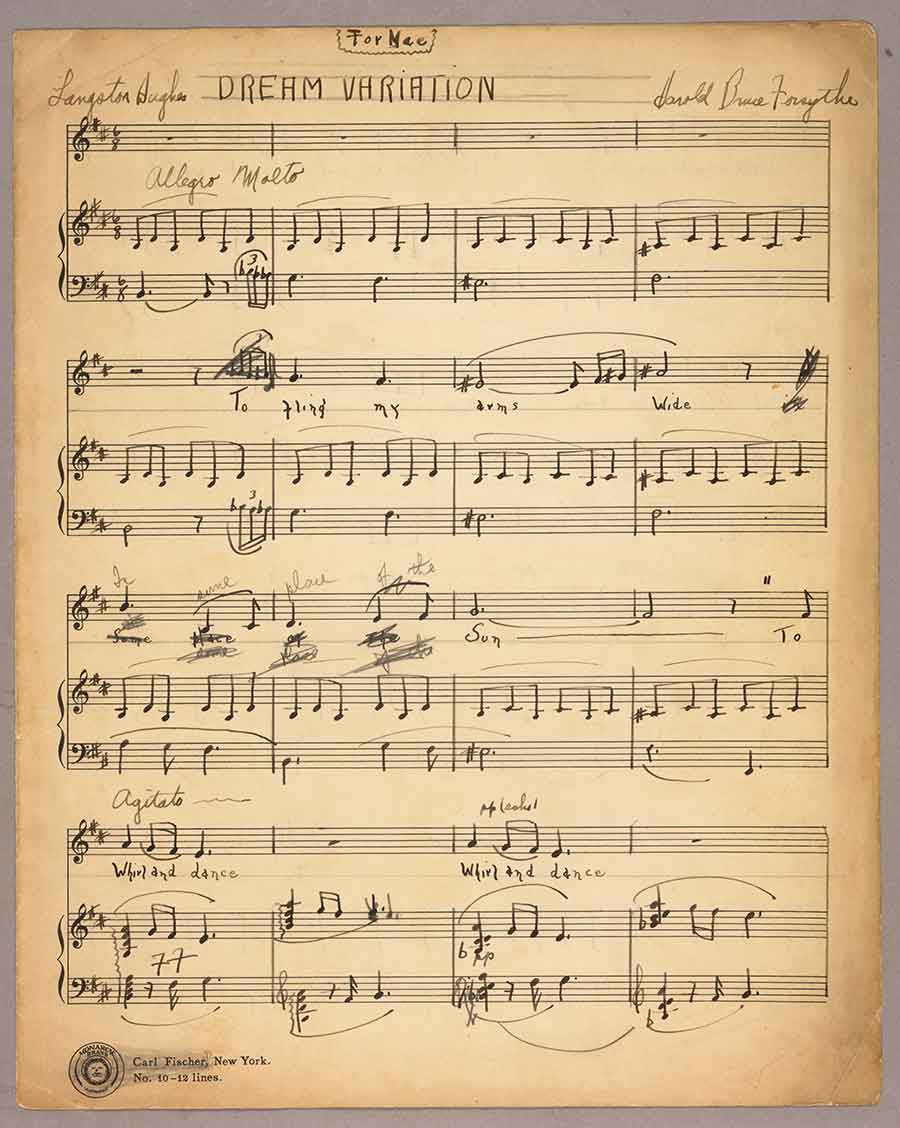

The first page of Harold Bruce Forsythe’s score for “Dream Variation,” with words by the poet Langston Hughes (1902–1967). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

During the 1920s and '30s, Forsythe composed several musical scores and collaborated with William Grant Still (1895–1978), often called the "Dean of African American composers." Forsythe introduced Still to the woman who became Still's second wife and collaborator, the pianist and librettist Verna Arvey. She and Forsythe had attended high school together.

The archive includes correspondence between Forsythe and Avery and Still, bearing witness to the overlap of personal and creative collaborations. These exchanges also demonstrate that the aesthetic concerns of Los Angeles's African American musical communities extended beyond the jazz and blues for which the vibrant Central Avenue scene was known.

Anne Harley, professor of music at Scripps College, has been teaching Forsythe’s compositions to her students for the past several years, and they have performed several of his works in public recitals. She is hoping to introduce Forsythe’s compositions into the performance repertoire by publishing the scores, many of which exist only in manuscript form. She is enthusiastic about introducing the works of the little-known Forsythe into the “Western canon of art song, which has unfairly and unfortunately excluded African American composers.”

Ramona Gonzalez and Dexter Story (along with Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, not pictured) perform Story’s rearrangement of Harold Bruce Forsythe’s “Flute of Marvel” in Rothenberg Hall. The performance was part of an event that launched The Huntington’s Centennial Celebration on Sept. 5, 2019. Photo by Jamie Pham.

The Huntington has also hosted performances of Forsythe’s work. This past fall, The Huntington launched its Centennial Celebration with a presentation that highlighted our three collecting areas—library, art, and botanical—and concluded with a performance of two works from our collections, including one by Forsythe.

Dexter Story—a Los Angeles musician, composer, arranger, songwriter, producer, and music director—was invited to reinterpret one of Forsythe’s compositions. Story invited musicians Ramona Gonzalez and Miguel Atwood-Ferguson to perform his rearrangement of Forsythe’s “Flute of Marvel,” a work inspired by the poetry of Li Bai (李白), a renowned Chinese poet of the eighth century. Forsythe's compositions attest to deep engagement with literature. Many of his works drew inspiration from writers, ranging from Li Bai to James Joyce and Wallace Stevens.

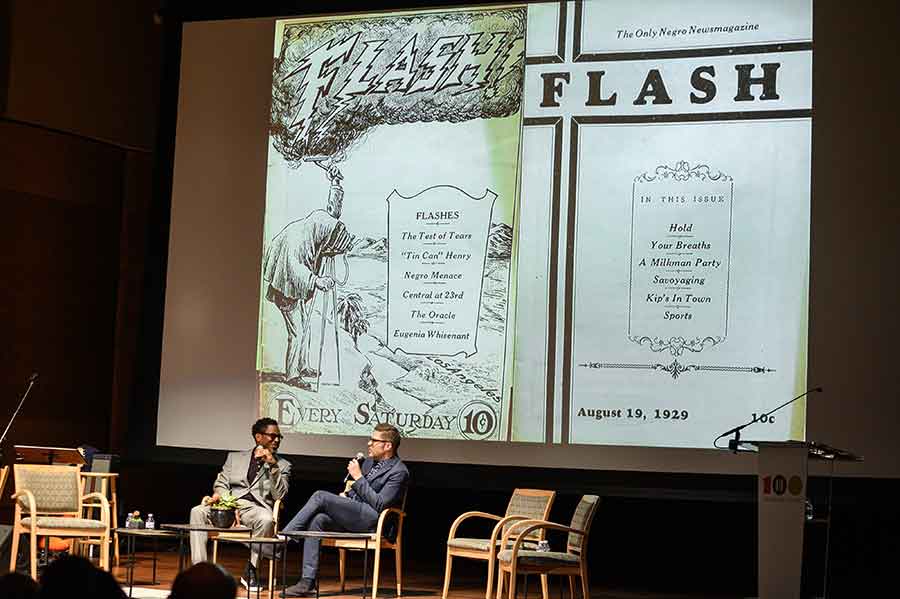

Dexter Story talks about Harold Bruce Forsythe with Josh Kun, professor and chair of cross-cultural communication at the University of Southern California, in Rothenberg Hall. On the screen appear images from the Los Angeles magazine Flash , an African American weekly to which Forsythe was a frequent contributor. The conversation was part of an event that launched The Huntington’s Centennial Celebration on Sept. 5, 2019. Photo by Jamie Pham.

Forsythe focused more on writing than music after he lost his hearing, contributing articles to several publications, including Flash magazine, a relatively short-lived but influential African American weekly published in Los Angeles and known for its writing about music. Forsythe’s contributions include criticism of the work of his friend William Grant Still.

During the Centennial Celebration launch, Story described to Josh Kun, professor and chair of cross-cultural communication at the University of Southern California, his experience of encountering rarely performed music in The Huntington’s Ahmanson Reading Room. “I had a sense of wonder, and fantasy, like I was opening up a world,” said Story. Moreover, he described an experience of identification with the composer. “I’m a Black kid from Los Angeles. I was born and raised in essentially the same area Forsythe was.”

In this excerpt from The Huntington’s Centennial Celebration launch, “100 Years of Music: Animating the Archive,” Josh Kun introduces Dexter Story, Ramona Gonzalez, and Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, who then perform Story’s rearrangement of Harold Bruce Forsythe’s “Flute of Marvel." The performance took place on Sept. 5, 2019, in The Huntington's Rothenberg Hall.

Story explained the tension he works through when interpreting an archival piece of music between being true to the original composition and interpreting it anew for a contemporary context. Story put Forsythe’s composition into Sibelius, a computer program that allowed him to “play” the multiple instrumental components of the score. He decided to introduce guitar, an instrument not used in the original composition. Forsythe loved triplets, Story noted, but Atwood-Ferguson, who played the keyboard during the performance, added a rolling component that was a distinct contribution to the piece.

Kun remarked during this conversation with Story that it is difficult to categorize Forsythe’s music. “It doesn't fit the standard paradigms of jazz and blues from Central Avenue, and it also doesn’t fit traditional paradigms of European art music.”

Forsythe’s musical style can’t be put in a box, but fortunately his scores were and have been preserved and made accessible to new generations of scholars, educators, and performers for further interpretation.

You can watch The Huntington's Centennial Celebration launch in its entirety here.

Karla Nielsen is curator of literary collections at The Huntington.