Posted on Wed., March 28, 2018 by

Portrait of John Ogilby, signed by William Faithorne, from Ogilby's 1663 translation of Virgil, Publii Virgilii Maronis opera per Johannem Ogilvium edita, et sculpturis aneis adornata (London, 1663). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

John Ogilby was born in Scotland in 1600, died in London in 1676, and was, at various points in between, a dancing master, a theatrical impresario, a translator of Virgil and Homer, and a widely read geographer.

He employed all his talents in April 1661, when King Charles II formally reclaimed the British throne after more than a decade of rule by Parliament and Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate. Ogilby took charge of “the Conduct of the Poetical part” of the restored king’s coronation procession through London. His “Speeches, Emblemes, Mottoes, and Inscriptions” graced four triumphal arches through which the procession passed. These constructions imitated, said Ogilby, those of “the antient Romanes, who at the Return of their Emperours, erected Arches of Marble.” True, his monuments were mere stage sets, probably constructed of wood and canvas, but they surpassed their ancient predecessors “in Number and stupendious Proportions.” They also reveal how Ogilby, and presumably many of those who witnessed his extravaganza, preferred to imagine England’s role on the eve of one of its greatest eras of colonial expansion.

The first page of Ogilby’s lavishly illustrated memorial of Charles II’s Coronation procession: The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (London, 1662). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Part of Ogilby’s genius as a promoter was to secure exclusive rights to publish accounts of the festivities he produced. The Huntington owns beautiful examples of the two volumes that resulted, most copies of which, Ogilby later lamented, perished in the 1666 Great Fire of London. The first, The Relation of His Majestie’s Entertainment Passing through the City of London, to His Coronation (1661) is a straightforward narrative of what the king and the crowds lining his way did and saw, quickly printed to prevent others from scooping the story. The far more elaborate second book, The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (1662), buries the original’s words beneath an unreadable mess of classical allusions, poetry, and other intellectual ostentations more elaborate than the ceremonies it describes.

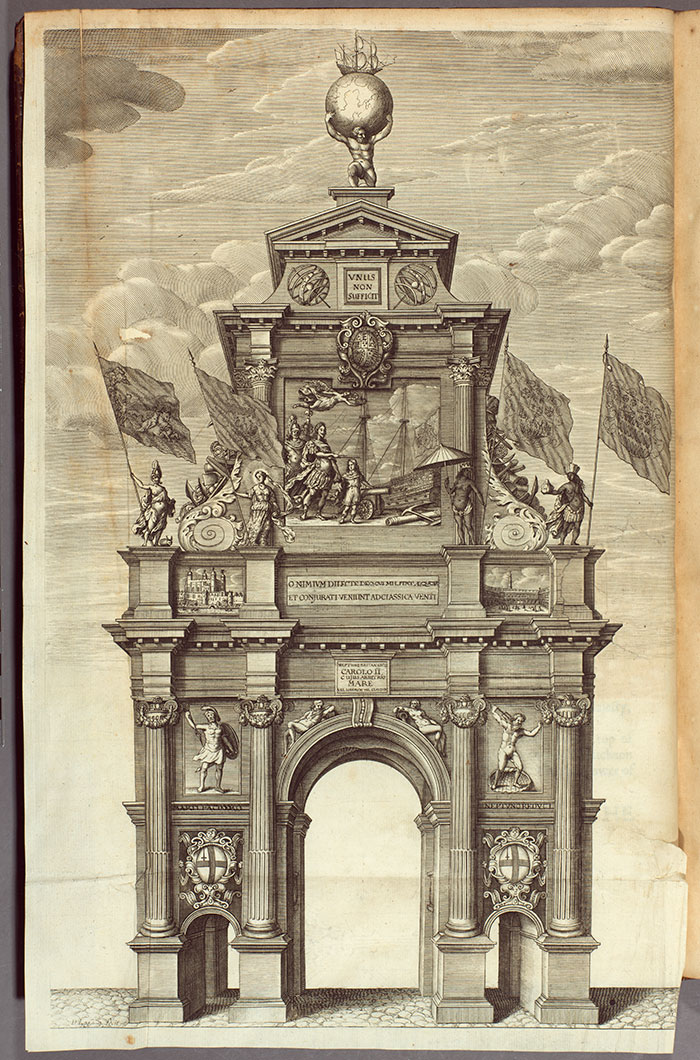

The impenetrability of the 1662 volume’s prose only highlights the wonders of its lavish illustrations. Five double-page spreads by Wenceslaus Hollar detail in order every horse and rider in the coronation parade. Each of the four triumphal arches gets a one-fold-out plate engraved by David Loggan: the first shows chaotic images of “Rebellion” conquered by “Loyalty”; the third and fourth portray, respectively, “The Temple of Concord” and “the Garden of Plenty” promised by the restoration of the monarchy.

Charles II’s Coronation Procession, from John Ogilby, The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (London, 1662). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The image of the second arch, erected in Cornhill near the Royal Exchange, is perhaps the most fascinating. King Charles would have had to crane his neck to glimpse what those watching the parade from rooftops would see first: Atlas holding a globe topped by an enormous sailing ship. Beneath these tottering figures, a pair of “Celestial Hemi-spheres” flanked a quotation from the ancient Roman poet Juvenal about Alexander the Great: unus non sufficit [orbis], “one world is not enough.” Beneath this favorite slogan of globally ambitious early modern kings was an emblem with the motto of the royal Order of the Garter, Honi soit qui mal y pense, “Shame on him who thinks ill of it.” Two other Latin inscriptions completed the homage to the restored king as lord of the waters: “For thee O Jove’s delight, the Seas engage / And muster’d winds, drawn up in Battle, Rage,” stated one. “British Neptune, Charles II, ruler of the seas, whether open or closed,” proclaimed the other.

Well-read viewers would recognize in this a reference to the debate between the Dutch legal theorist Hugo Grotius and his English critic John Seldon over whether the seas were Mare Clausum, exclusive possessions of particular monarchs, or Mare Liberum, open to all. Either way, Charles II would prevail. Anyone who missed the Latin messages would hear them repeated in plain English by costumed sailors who sang verses such as this from a stage-set ship at curbside:

King Charles, King Charles, great Neptune of the Main!Thy Royal Navy rig,And We'll not care a FigFor France, for France, the Netherlands, nor Spain. The Turk, who looks so big,We'll whip him like a Gig

The Naval Arch, from John Ogilby, The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (London, 1662). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The centerpiece of the entire display—best seen from third-floor balconies along the route—was a huge painting of “King Charles the First, with the Prince, now Charles the Second, in His Hand . . . leaning on a Cannon.” Flanking the martyred father and his restored son were “living Figures, representing Europe, Asia, Africk, and America , with Escutcheons, and Pendents, bearing the Arms of the Companies trading into those parts.” The woman representing Africa held an umbrella to defend herself from the blazing sun (and perhaps from young Charles’s cannon), carried a pomegranate in her hand, and wore a crown of corn and ivory. The pomegranate was an abstruse classical reference to the goddess Juno, the corn symbolized “the Fertility of the place,” and the ivory evoked “the great number of Elephants, bred in that part of the World.”

The classics, of course, could provide no help in personifying America, which Ogilby could only portray as “Crown’d with Feathers of divers Colours, on her Stole a Golden River, in one Hand a Silver Mountain.” The river was the Amazon, the mountain was the silver mine of Spanish Potosí, and neither image conveyed anything about the North American and Caribbean colonies where tens of thousands of English colonists actually lived in 1662. Nor did the embodiment of Africa hint at the tens of thousands of captive laborers who would soon be leaving the continent’s shores on English ships to slave and die on English plantations. Instead, Ogilby portrayed a learned, aristocratic, fantasy empire, where classical models combined with elite guilds of merchants to reap riches and glory for king and nation.

The Naval Arch (detail), from John Ogilby, The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (London, 1662). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

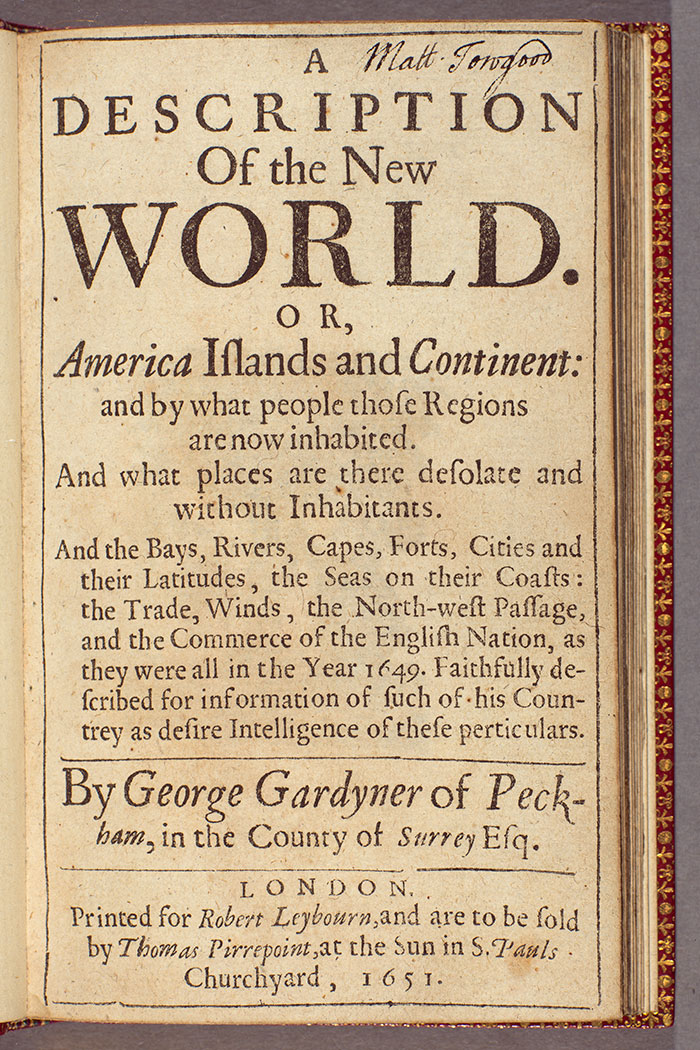

A decade before Ogibly’s arch fantasies spanned Cornhill and filled the pages of his lavish memorial volume, a tiny unillustrated pamphlet in The Huntington’s collections had painted a very different prose picture. Its author, George Gardyner—who had actually been to the colonies rather than just read about them—shared Ogilby’s hope that Englishmen would “grow great and famous and extend their authority and name beyond either Roman, Grecian, Assyrian or Persian Nations.” But alas, he had to say, “the trade of America is prejudiciall, very dishonest, and highly dishonourable to our Nation.” Far from being admired as modern Neptunes, his fellow Englishmen were “upbraided by all other Nations . . . for selling our own Countreymen for the Commodities of those places.” He was talking about the commerce in indentured servants, people of England’s “own Nation, which have most barbarously been stolne out of their Countrey” to harvest sugar in Barbados and tobacco in Virginia.

Gardyner’s portrait of what went on in New England was no more flattering. The puritans there, he said, “punish sin as severely as the Jews did in old time, but not with so good warrant.” Moreover, “they have brought the Indians into great awe, but none to any Gospell knowledge.” These were not pretty pictures. No wonder Ogilby preferred images from two thousand years distant in his past to those from four thousand miles away in his present.

The title page of John Gardyner’s far less rosy picture of England’s colonies: A Description of the New World (London, 1651). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Daniel K. Richter, the 2017–18 Robert C. Ritchie Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington, is a Roy F. and Jeannette P. Nichols Professor of American History and the Richard S. Dunn Director of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Among his publications areFacing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early AmericaandBefore the Revolution: America’s Ancient Pasts.

You can listen to Richter’s Distinguished Fellow Lecture, “The Lords Proprietors: Land and Power in 17th-Century America,” on SoundCloud.