The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Knowing the Earth, Then and Now

Posted on Sun., Jan. 1, 2017 by

Orbit Pavilion is on view on the Celebration Lawn (across from the Celebration Garden) through Sept. 4, 2017. Photo by Kate Lain.

We denizens of the 21st century have numerous ways to learn about our planet: seismographs, submersibles, and airborne snow observatories cover every continent. Some of the most remote Earth science instruments are the satellites that circle our globe to gather data about droughts, hurricanes, and tectonic shifts. NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Orbit Pavilion, currently on display at The Huntington, brings these far-away vessels back to Earth, but with a twist.

After wending our way into the shell-shaped structure, we are immersed in the sounds of a wave crashing, a frog croaking, and wind tangling with tree branches—each of which corresponds to the mission of one of NASA’s 19 Earth science satellites. While wrapped in the Orbit Pavilion’s aluminum-and-steel frame, we rediscover the world not with our eyes but with our ears.

In 1851, spaceships were mere fantasies and our delicate blue dot couldn’t be captured in a photograph. But John Wyld, a prolific map publisher and honorary geographer to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, wanted to give people the world—and demonstrate how much the British Empire knew about it. As London prepared for the Great Exhibition of the same year, Wyld constructed a “Colossal Globe” right in the middle of Leicester Square. This 60-foot orb stood in that very spot for 10 years. Gawkers did not admire the Alps or the Indian Ocean by gazing up at the monument. Instead, they were encouraged to journey inside to the center of the Earth and see how Wyld had turned its outsides in.

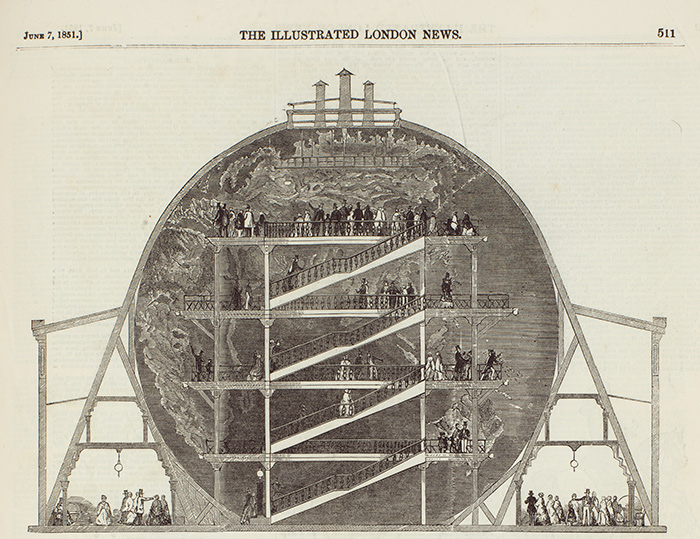

Image of John Wyld’s globe from Illustrated London News, vol. 18, Jan.–June, 1851; June 7, 1851, page 511. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Visitors entered the globe from a small opening in the Pacific Ocean. From there, they could choose to marvel at the world’s physical geography from four loggias. An image from an 1851 issue of the Illustrated London News—held in The Huntington’s collections—shows visitors climbing four interlocking staircases to view the globe’s enormous relief map. The highest peak of the Himalayas was a mere 1.5 inches tall, and the United States was 23.3 feet wide. Volcanoes and snow-capped mountains rose and fell; deserts and craters appeared as deep depressions on the map’s surface. All this topography was rendered in plaster, paint, wood, cotton wool, and small white crystals.

Victorians were curious about the natural world. Alongside progress reports about the building of Wyld’s globe, fashionable periodicals updated readers about new demonstrations that made the rotation of the Earth visible. They devoted precious column space to the minutes of The Royal Institution, the nation’s premier organization for public engagement with science. And many periodicals ran lavish advertisements for telescopes, microscopes, and chemistry textbooks. Literate women and men had grown so familiar with contemporary scientific research that Punch, London’s satirical magazine, could joke about competing theories concerning the composition of the Earth’s inner core: “Mr. Wyld has made a grand discovery. He has satisfactorily proved that the interior of the globe is not filled with gases, according to Agassiz; or with fire, according to Burnet; neither has he filled it, like Fourier, with water. No, Mr. Wyld has now shown us that the interior of the globe is occupied by immense strata of staircases.”

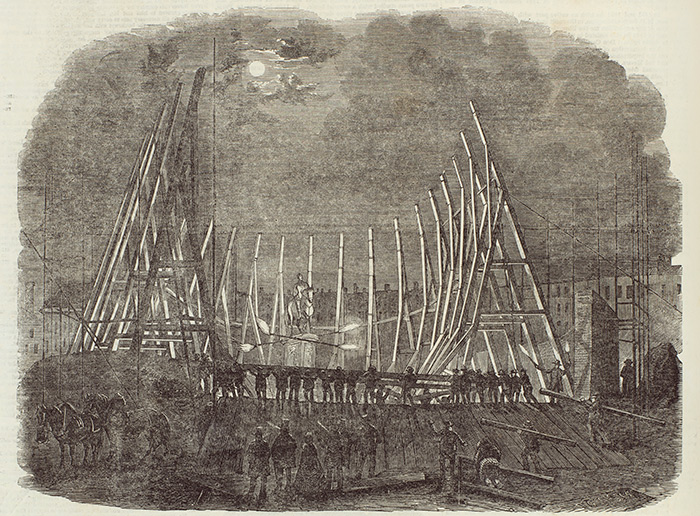

Illustration of John Wyld’s globe under construction from Illustrated London News, vol. 18, Jan–June, 1851; March 22, 1851, page 234. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Despite these controversies, Victorian geologists understood that the Earth was millions of years old. They knew that layers of rock and soil were the residue of different epochs. And they were beginning to learn that many creatures had come, gone, and evolved as the Earth aged.

Still, there was more to discover. No one had stepped foot on Antarctica. Few could have pictured that oxygen, silicon, aluminum, iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium comprised the Earth’s crust. And artificial satellites were a century away.

If Wyld’s globe gave Victorians a static world, frozen in time, NASA/JPL’s Orbit Pavilion helps us consider its changes in the here and now. As we ring in the New Year, this sounding nautilus provides us with an unusual opportunity to reflect on our planet—to hear its diverse wonders, and to consider how we learn about our home, now and in the years to come.

Related content on Verso:

Hearing NASA’s Earth Science Satellites (Nov. 15, 2016)

Melissa Lo is Dibner Assistant Curator of Science, Medicine, and Technology at The Huntington.