The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

LECTURES | "More Like a Sermon"

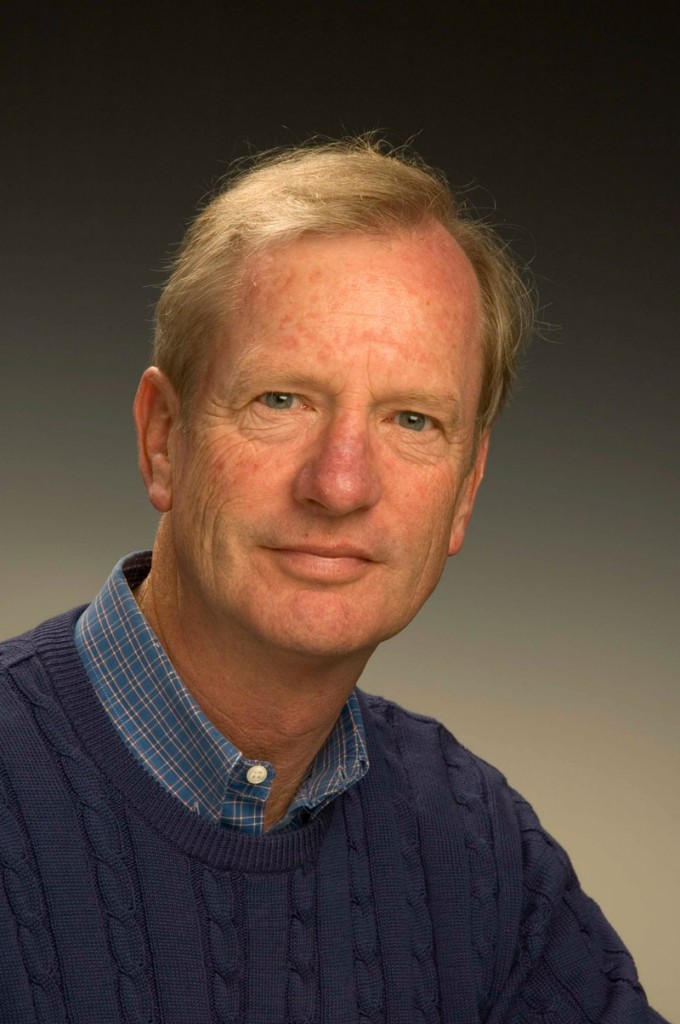

Posted on Mon., Jan. 23, 2012 by

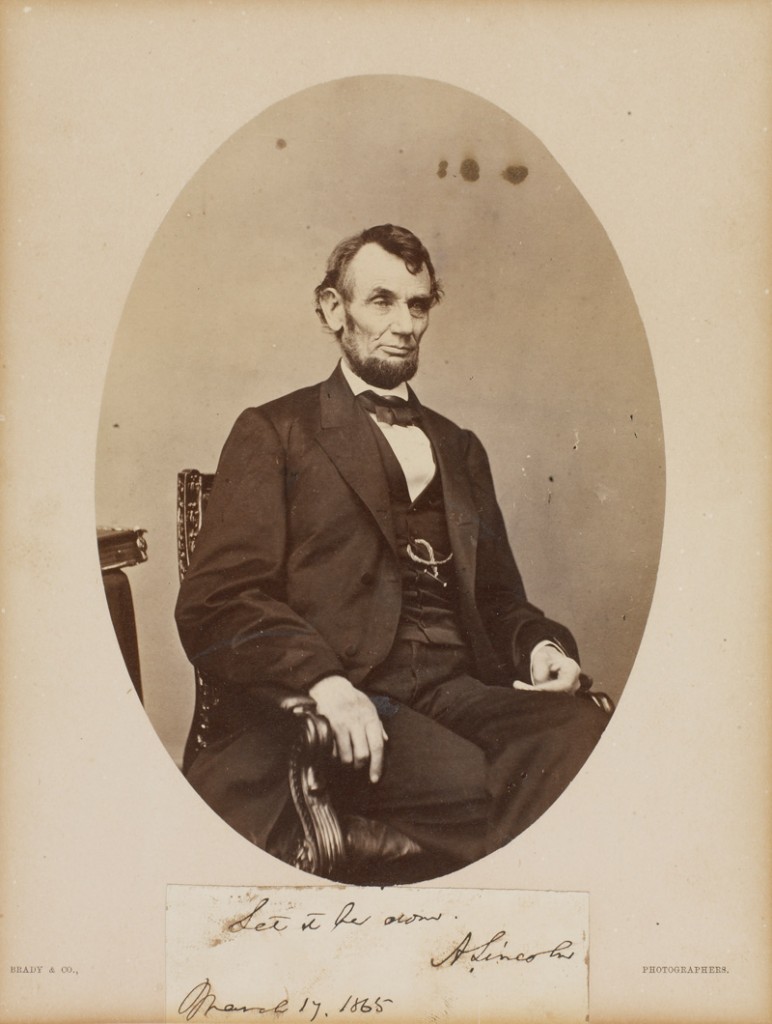

Photograph of Abraham Lincoln includes a handwritten note reading "Let it be done," signed and dated by Lincoln on March 17, 1865. (The photograph itself was taken in 1864 at Matthew Brady's Washington D.C. studio by his partner, Anthony Berger. It is known as the "five dollar pose," because the likeness was used as the basis for the engraving on the $5 bill.) Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When Abraham Lincoln completed his Second Inaugural Address in the waning days of the Civil War, Frederick Douglass remarked that "the address sounded more like a sermon than a state paper." In a lecture at The Huntington Wednesday night, historian Harry S. Stout will explain how that speech was an American sermon to the world.

"I'm going to compare Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address with what I consider to be the other great American sermon--Jonathan Edward' 'Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,'" says Stout, whose work has straddled Edwards' Puritan New England of the 1700s and the great conflagration of the mid-19th century. The professor of American religious history at Yale University is general editor of the works of Jonathan Edwards, and he is the author most recently of Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War (Viking, 2006).

Stout says those two speeches were delivered by people with very different theologies or philosophies, however they are both concerned—even obsessed—with an angry God. For Edwards, the source of God's anger is sin, whereas Lincoln's God is motivated by his reaction to slavery. And lingering in the margins of his lecture, Stout explains, is the reaction of Frederick Douglass, who chided Lincoln for indicting him along with everyone else, North and South. "He's not angry at me," said Douglass, "he's angry at white America."

Stout is the Rogers Distinguished Fellow in 19th-Century American History this year at The Huntington, succeeding his Yale colleague David Blight, whose lecture last year also touched on Douglass and who spent his year at The Huntington working on two books, the newly published American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era and his upcoming biography of Frederick Douglass.

Like Blight, Stout has made good use of the Huntington collection over the years. "I first came here in 1978 while working on my book New England Soul: Preaching and Religious Culture in Colonial New England," Stout recalls. In the second edition of that book, published last month by Oxford University Press, Stout added a new introduction in which he described his "Huntington epiphany." Until a Huntington curator showed him manuscripts of sermons from the 17th and 18th centuries, Stout had relegated his attention to what he had been finding in printed books. He found out that manuscripts contained the rough notes and revisions that were more accurate records of what was said from the pulpit each week. "After my Huntington epiphany, I then scoured all the libraries and historic societies for manuscripts of sermons," Stout recalls.

Stout is now halfway through a year digging in the Huntington archive, where he has devoted much of his time to the papers of Richard Clough Anderson Jr. (1788-1826), whose father was on that famous boat with George Washington crossing the Delaware. The papers cover three generations of the Anderson family, including Robert Anderson, the major who surrendered Fort Sumter in April 1861.

"They are a tremendously accomplished family that is just below the radar screen of greatness," Stout says, "so that nobody has heard of them. It is incredible how many families are like this in American history that never make it into the books." That is, until Stout wraps up his year of research at The Huntington and begins drafting his next book.

Stout's lecture takes place Wed., Jan. 25, at 7:30 pm in Friends' Hall and is free and open to the public.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.