The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Legacy in Silver

Posted on Wed., Sept. 24, 2014 by

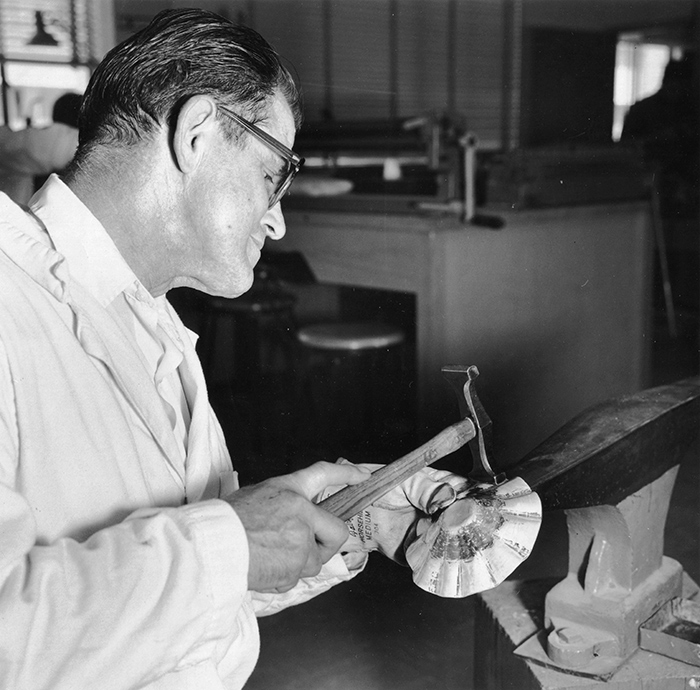

Hudson Roysher at work in his studio in this undated photo.

“I ask myself: ‘Will this thing last for at least 100 years?’” Hudson Roysher told the Los Angeles Times in 1967. “My work has to be of the best quality that I am capable of at the time.” Roysher, a renowned silversmith whose work is displayed in The Huntington’s Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art, died in 1993, leaving behind a legacy of exquisite craftsmanship—from Buffalo to Syracuse to Los Angeles. Much of his work was created expressly for churches: chalices and candelabras, for instance. In fact, the only existing collection of Roysher’s secular silver now resides at The Huntington, and it is sublime. Said Harold B. “Hal” Nelson, The Huntington’s curator of American decorative arts, “These pieces, along with his papers, embody his lifelong association with The Huntington.”

The silver was a gift from Roysher’s children, Martin Roysher and Allison Wittenberg. It came to the institution in 2012 along with his archives, a treasure trove of material documenting his extraordinary life and career.

A born natural, Roysher was largely a self-taught silversmith who began honing his craft as a teenager and took first prize in the annual Cleveland Art Museum show of 1934 at the age of 23. In the 1940s, Roysher’s architecturally sophisticated and contemporary secular works were sold at Gump’s, the famed San Francisco luxury retailer, while his ecclesiastical works were commissioned by numerous Southern California churches from the 1950s through the 1970s. He led the metals program at California State University, Los Angeles, for several decades and became chairman of the art department in 1971, thus influencing generations of silversmiths through his teaching, writings, and workshops.

Hudson Roysher, Decanter Set, ca. 1948, silver and Sumatra cane. On view in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art.

“The relationship between Hudson Roysher and The Huntington goes back many years,” said Nelson. “While completing a Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Southern California, he spent time researching and writing his master’s thesis here. Furthermore, his wife, Alli, was an art teacher in Pasadena and brought her students to The Huntington on field trips. She later became a docent at the nearby Gamble House and served as one of the first consultants to The Huntington’s special gallery of early 20th-century Pasadena architects Charles and Henry Greene.”

In a few years, Nelson plans to curate an exhibition at The Huntington of Roysher’s work. In the meantime, to get a sense of Roysher’s prowess, make your way over to the American art galleries; on display in the room with the Edward Weston photographs is a spectacular decanter set (pictured above), crafted from silver and rattan. Fans of Roysher were continually astonished by what he was able to do with metal: he was an alchemist extraordinaire. He is said to have once remarked, “Looking at a piece of silver is like looking into a pool of clear water. There is a depth to it that other metals do not have.” Surely one could say that about the artist himself.

Bonnie Taylor is assistant director for donor engagement at The Huntington.