Posted on Wed., Feb. 27, 2013 by

Technicians from Gale Cengage onsite at The Huntington. They are completing the scanning of 5,000 books from The Huntington's collection on the history of science. Photo by John Sullivan, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Henry Edwards Huntington was born on this day in 1850, which makes today Founder’s Day at The Huntington. You can mark the occasion by downloading last week’s Founder’s Day talk by David Zeidberg, the Avery Director of the Library.

Zeidberg’s lecture is the comprehensive answer to one of the most common questions he receives: “So, is The Huntington digitizing everything in the library collection?”

The answer is a complicated one.

Some of its most iconic texts—from Chaucer’s Ellesmere manuscript of The Canterbury Tales to The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin—have recently been made available in digital form and are now accessible via the Huntington Digital Library.

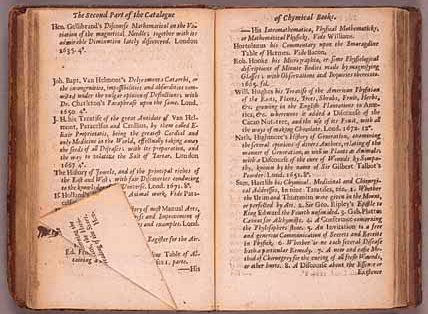

Copy of A Catalogue of Chymicall Books, by William Cooper (1675), from the personal library of Isaac Newton, who folded pages of interest in many of his books. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

With massive archives, a little strategy is in order. In 2007, Jennifer Watts, The Huntington’s curator of photographs, secured a “We the People” grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to fund the digitization of 6,000 pictures the Maynard Parker archive of photographs of Southern California architecture, which totals more than 60,000 images. The resulting database is a representative cross-section of the entire collection, accessible to scholars and the public alike. A future project is planned for The Huntington’s collection of Jack London photographs.

The Huntington also participates in commercial endeavors. By contributing to database subscription services such as Early English Books Online, the 18th-Century Catalog Online, and American History and Culture Online, The Huntington receives royalties based on sales of the databases to other libraries. For the past five months, a private company called Gale Cengage has funded its own team of technicians who have been scanning a selection of 5,000 books from The Huntington’s archive on the history of science.

Zeidberg champions such efforts but reminds us that digitization has its limits. First of all, the sheer numbers—The Huntington has more than 9 million items—make it impossible to digitize everything. And even when we provide a copy of a book to a digital database, scholars are still missing the complete picture. For example, if you log onto Early English Books Online, you’ll see a Huntington copy of Isaac Newton’s Principia (1687). But The Huntington has six other copies of the book, including one with marginalia in Newton’s own hand.

Newton also had a habit of folding the corners of pages in his own books to mark pages of interest—in the process bedeviling today’s archivists who attempt to digitize such books while preserving the material aspects of the paper.

“The counterintuitive result of all of these efforts,” concludes Zeidberg, “is that the more we digitize our own copies—and identify what we have to a wider audience—the more scholars want to see the originals.”

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.