The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Life of Skip Brack

Posted on Tue., Nov. 20, 2012 by

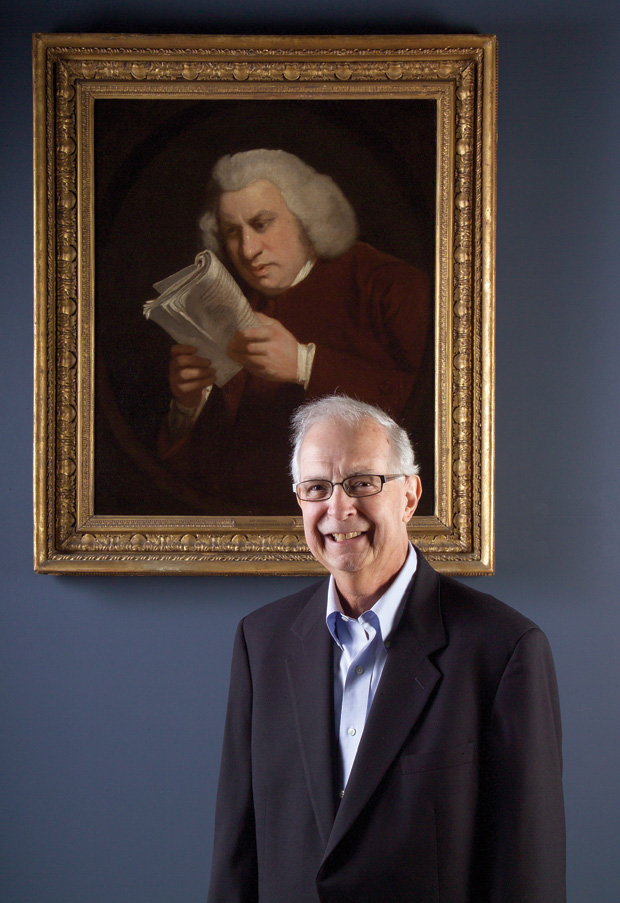

Skip Brack in 2009, standing in front of The Huntington’s painting of “Blinking Sam” (1775), by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which was donated to The Huntington by noted Johnson collector Loren Rothschild, who was also a dear friend to Brack. Photo by John Sullivan, Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Bibliographers seldom get much attention, especially when they choose the literary giant Samuel Johnson as their subject. Scholar O M “Skip” Brack Jr. relished living in the shadow of such greatness, annotating scholarly editions of Johnson’s writings while earning the respect and admiration from those who meant the most to him—his fellow Johnsonians and his students. Brack passed away on Nov. 8, 2012. He was 73.

“Skip was a reader at The Huntington for more than 40 years,” said Alan Jutzi, Avery Chief Curator of Rare Books, “and during that time he contributed substantially to its scholarly community and became a friend to us all.” Jutzi and Brack collaborated—along with Johnson collector Loren Rothschild—on the 2009 Huntington exhibition “Samuel Johnson: Literary Giant of the Eighteenth Century,” which coincided with the tercentenary of Johnson’s birth. Brack and Rothschild wrote the accompanying catalog published by Rasselas Press.

“I met Skip a few decades ago,” recalled Rothschild. “Since then he has been my closest advisor and wonderful friend. I cannot count the times that he has saved me from making a mistake about the 18th century; or the times that he has given me essential advice about collecting Samuel Johnson. Our Johnsonian world has recognized that our last project together, the catalog of the 2009 Samuel Johnson exhibition, was an exceptional work—certainly the best memorial of the many tercentennial celebrations. I will miss Skip. I am gratified to have known him. And sad that we will not work together again.”

Brack spent most of his career in the English department at Arizona State University, arriving there in 1973 after directing the Iowa Center for Textual Studies at the University of Iowa in the late ’60s and early ’70s. He retired from ASU in 2008. Aside from his Johnson work (he was a member of the editorial committee of the Yale edition of the Works of Samuel Johnson and edited three of its volumes), he was the founding editor of the Works of Tobias Smollett, published by the University of Georgia Press from 1988 to the present. He was also a pillar of the Samuel Johnson Society of the West.

Society secretary Myron Yeager summed up Brack’s active involvement in any number of organizations: “Like Johnson, Skip would, I believe, say, ‘Sir, I look upon every day to be lost, in which I do not make a new acquaintance.’”

“He was a textual editor par excellence,” writes Professor Robert DeMaria Jr. in Brack’s obituary, “skilled at comparing the extant states of a published work and deciding which printing should be followed in a definitive scholarly edition. With a skill that few could match Skip could distinguish between those variants, in a long list of possibilities, which should be included in the text and which should be consigned to alternatives listed merely in the textual apparatus.”

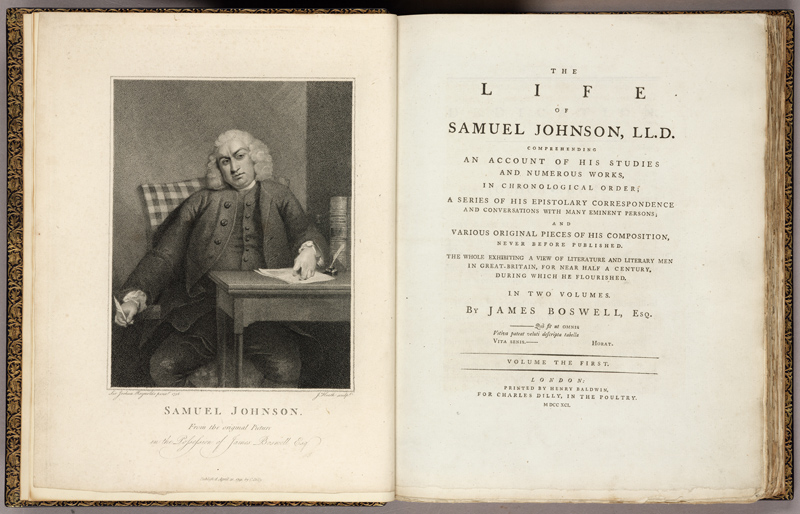

Frontispiece and title page of James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, 1791, the biography that overshadowed that by the lesser known John Hawkins. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Frontispiece and title page of James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, 1791, the biography that overshadowed that by the lesser known John Hawkins. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.One such text that emerged from his work was Sir John Hawkins’ Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D., a biography long overshadowed by James Boswell’s more famous Life of Johnson. Brack’s new annotated edition of Hawkins’ book (published in 2009) makes the lesser known biography available in complete form for the first time in nearly 200 years.

As with his work on Johnson and Smollett, Brack’s job was to identify passages in Hawkins’ text that needed explanation or clarification. “I’ve been working in the 18th century for 45 years,” said Brack in the fall/winter 2009 issue of Huntington Frontiers, “and if I don’t understand something, what are the chances that my reader will?” In the process, Brack used The Huntington’s holdings to refer to the same texts that Hawkins likely used to flesh out his description of the people who crossed Johnson’s path. The difference is that Hawkins didn’t usually identify his sources, whereas Brack’s painstaking endnotes reveal them, along with other material that he tracked down at The Huntington. The result is a textured life of Johnson.

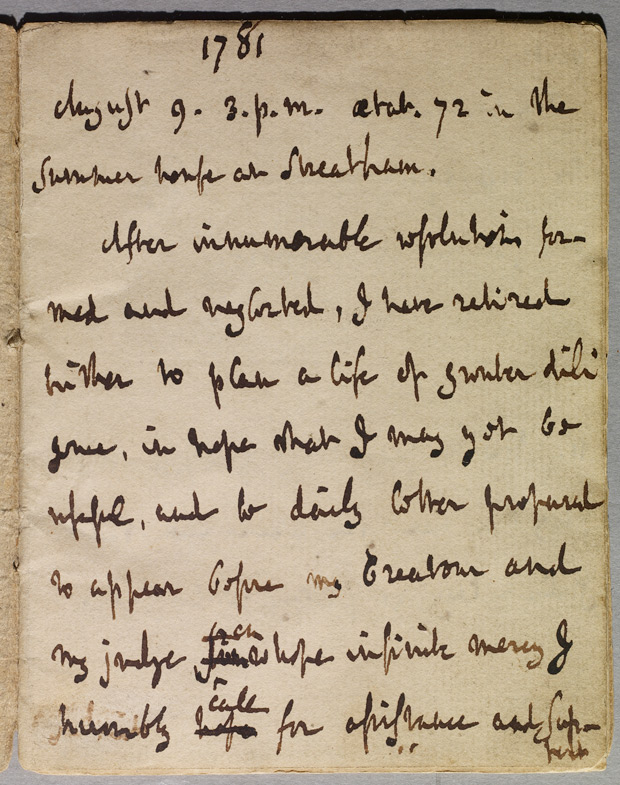

Samuel Johnson’s diary, open to Aug. 9, 1781. The page reads: “After innumerable resolutions formed and neglected, I have retired hither to plan a life of greater diligence, in the hope that I may yet be useful…. My purpose is to pass eight hours every day in some serious employment.” Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On the website of ASU’s English department, chair Maureen Daly Goggin pays tribute to another one of Brack’s legacies: “He was a much beloved teacher and mentor to undergraduate and graduate students who gave him top marks and glowing comments for his clarity, helpfulness, knowledge, and caring. In 1991 he received the prestigious ASU Alumni Association Faculty Achievement Award, and in 2000 the ASU Graduate College Outstanding Mentor Award. For both of these honors he was nominated by his students, and for Professor Brack that fact meant a great deal.” Even after his retirement, Brack won the Jay Fliegleman Mentoring Award in 2010 from the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.

“In his academic work and in his personal relationships,” says Huntington curator Alan Jutzi, “Skip had an engaging way of highlighting the humanity of historical figures as well as individuals in his life. The brilliant, troubled writer Samuel Johnson, who Skip studied intensely most of his career, was best understood as a human being with the same appetites, conflicts, and fears that all of us live with. This approach enlivened his classroom and was the reason, I believe, he had so many dedicated students. It also enhanced his scholarship and deeply enriched our friendship.”

Brack is survived by his wife, Cynthia Burns; his son, Matthew; and his grandson Jakob. Donations in his memory may be sent to the Huntington Library, Attention: Cris Lutz, Library Fund.

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.