The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Lincoln’s Last Hours

Posted on Tue., April 14, 2015 by

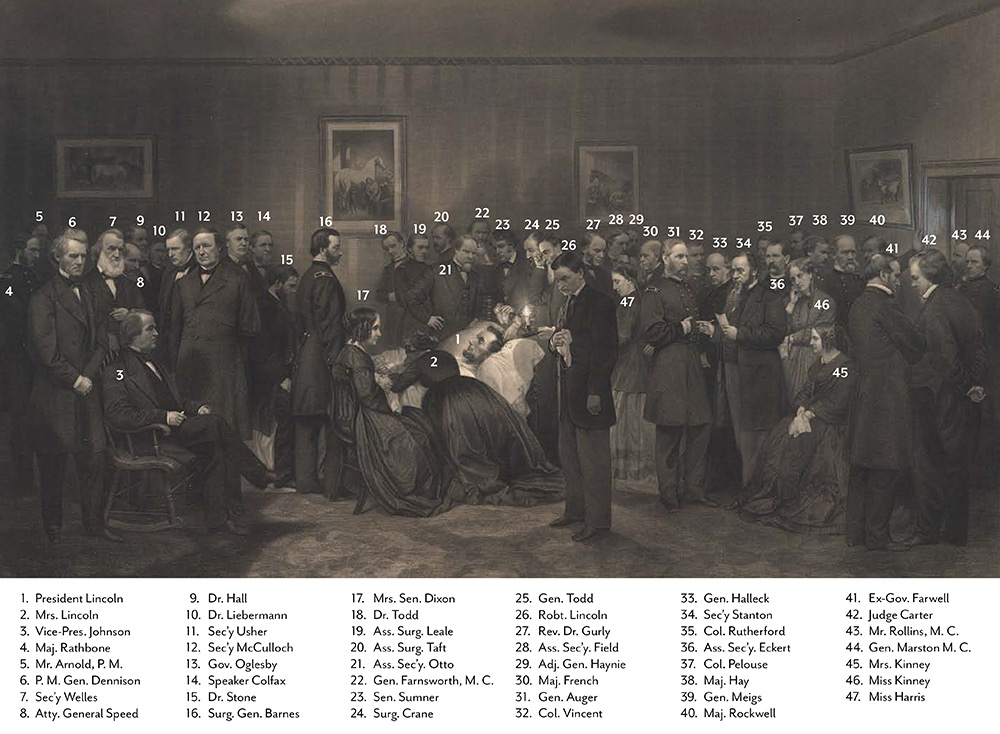

The Assassination of President Lincoln. At Ford’s Theatre, Washington, on the night of Friday, April 14, 1865, lithograph,1865. Unidentified artist. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On the evening of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln as he attended a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. The president died at 7:22 a.m. the next day in a boarding house across the street from the theater, surrounded by a small group of shocked witnesses. Four years of warfare had ended less than a week before with the surrender of the Confederacy. What were people to make of this violent, incomprehensible act?

A host of printmakers immediately stepped into the fray, supplying a raft of images that offered anguished Americans ringside seats to the president’s final hours. Most depictions embellished the truth—some to an outlandish degree.

One afternoon in 2012, while deep in preparations for a then-forthcoming Civil War exhibition, I came across a large folder in a bottom-most drawer. The penciled label stated simply, “uncataloged Lincoln print,” a terse description that gave no real indication of what lay inside. One thing I’ve learned in 20-plus years of working at The Huntington: it’s always worth taking a look.

The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, c. 1868, line and stipple engraving (artist’s proof), by John B. Bachelder (1825–1894), after a painting by Alonzo Chappel (1828–1887). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Cracking open the folder, I saw a dying president’s outsized head illuminated by a single candle flame. Mary Todd Lincoln kneels by her husband’s bedside, overwhelmed by grief. The couple’s eldest son, Robert, stands in the foreground with a handkerchief clutched to his chest. A mob of onlookers faces this way and that; altogether there are 46 mourners in a bedroom that, in reality, contained only a few people. The engraving, designed by artist and publisher John B. Bachelder (1825-1894), is enormous and intricately rendered. It’s impressive and—let’s face it—a little weird.

On hearing of Lincoln’s assassination, Bachelder, who recounted being in the nation’s capital on that sorrowful day, resolved “at once . . . to collect such materials as should be necessary for an historical picture commemorating that sad scene.” He went about the task in his characteristically ambitious style: creating a design, lining up scenic painter Alonzo Chappel (1828–1887), and contacting the estimated 55 people who had visited Lincoln that fateful night.

Bachelder persuaded many of them to pose for famed Civil War photographer Mathew B. Brady in stances that Chappel would work into the final composition. It is striking that even the notoriously private Robert Lincoln consented to this bold request so soon after the tragic loss of his father.

![Veterans with John B. Bachelder [standing] at the 29th Ohio Infantry Monument, Gettysburg, ca. 1887. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/uploads/2015/04/Lincolndeathbed-3.jpg)

Veterans with John B. Bachelder [standing] at the 29th Ohio Infantry Monument, Gettysburg, ca. 1887. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A full three years elapsed before Chappel’s painting The Last Hours of Lincoln was unveiled. Testimonials overwhelmingly praised the accuracy of the people represented, glossing over the veracity of the scene itself. The representation is decidedly not visual reportage.

Ever the entrepreneur, Bachelder wasn’t through. He proposed making prints of the painting for anyone hankering to own a “genuine work of art.” The top-most category included an “artist’s proof” offered by subscription at $100 a pop. It appears that only three of the deluxe line and stipple engravings were ever produced, including the one I’d discovered. The whereabouts of the other two engravings—should they still exist—are unknown.

The mass marketing of The Last Hours of Lincoln eventually fizzled, along with the demand for scenes of Lincoln’s death. Indeed, Bachelder himself soon moved on, directing his prodigious energies toward Gettysburg, efforts that would insure the battlefield’s legacy as the war’s most sacred space. He spent 30 years gathering soldiers’ battle recollections, writing a congressionally funded eight-volume history, and supervising the placement of monuments on the battlefield.

In 1908, on the eve of centennial celebrations for Lincoln’s birth, a muddy reproduction of The Last Hours of Lincolnsurfaced briefly. Someone named “M. David” produced an exceedingly poor print, but—hallelujah!—included a key that identified all of the people immortalized in this mythic deathbed scene.

Key to The Last Hours of Lincoln. Based on a key published in 1908 by M. David. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Last Hours of Lincoln appeared in The Huntington’s exhibition “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War,” which ran from Oct. 13, 2012, to Jan. 14, 2013. It also appears—with the key—in the recently released Huntington Library Press book of the same title by Jennifer A. Watts. The book is available for purchase at the Huntington Store.

Through the Huntington Digital Library, you can listen to a rare audio recording of an eyewitness, Joseph H. Hazleton (1855-1936), recounting Lincoln’s assassination. You will find the articles “Lincoln’s Body, in Life and Death” and “Lincoln’s Last Breath” in the Fall/Winter 2014 issue of Huntington Frontiers.

Related content on Verso:

The Union Forever (March 31, 2015)

Lincoln’s Signature Accomplishments (Jan. 30, 2015)

Remembering Gettysburg (Nov. 19, 2014)

Jennifer A. Watts is curator of photographs for The Huntington.