The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Living and Writing on the Edge

Posted on Fri., Aug. 14, 2015 by

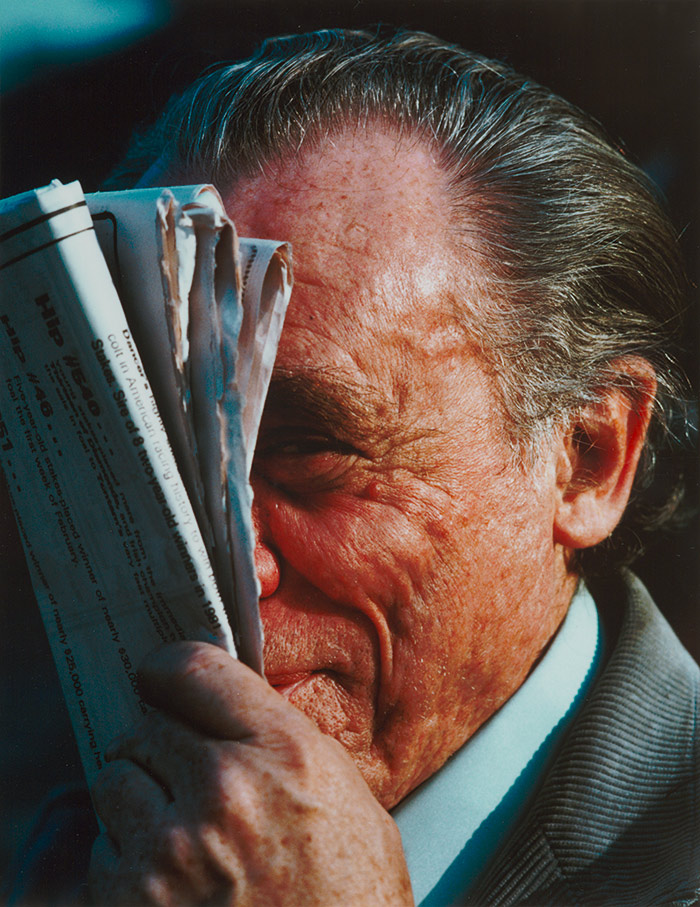

“ . . . I want to stay in the game a while longer, so I can piss a lot of people off. If I live to be eighty, I’ll really piss them off.” From “Paying for Horses: An Interview with Charles Bukowski,” by Robert Wennersten, 1974. Charles Bukowski, who loved betting on horses, holding a racing form. Photo by Michael Montfort, 1982. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Poets, of course, aren’t the only ones to suffer in our world, they just talk more about it.

—Charles Bukowski, from “Looking Back at a Big One.”

Sunday, August 16, marks the 95th anniversary of the birth of Charles Bukowski (1920–1994), whose poems, short stories, and novels depicted ordinary men and women struggling to survive in an unforgiving world.

To celebrate his birthday, Bukowski fans in Southern California can head to his hometown, San Pedro, for “Charles Bukowski: The Laughing Heart,” a festival that will feature readings from books, reminiscences about his life, and a screening of the 2005 feature film Factotum—based on Bukowski’s 1975 novel of the same title—starring Matt Dillon and Lili Taylor. (For further information, check the website for the San Pedro Film Festival.)

Since Bukowski’s death, interest in his writings has flourished unabated among new generations of readers, as well as among his longtime fans and followers. Possessing one of the most original voices in 20th-century American literature, Bukowski lived and wrote on the edge—in the shadowy outskirts of society and the literary establishment. His poems and tales tell of his life among society’s outcasts—prostitutes, drunks, and gamblers. In telling these stories, he wrote in simple, natural language, repudiating formal literary subjects and conventions used by other writers. He strove to keep his writing “raw, easy and simple,” to grasp the “hard, clean line that says it.”

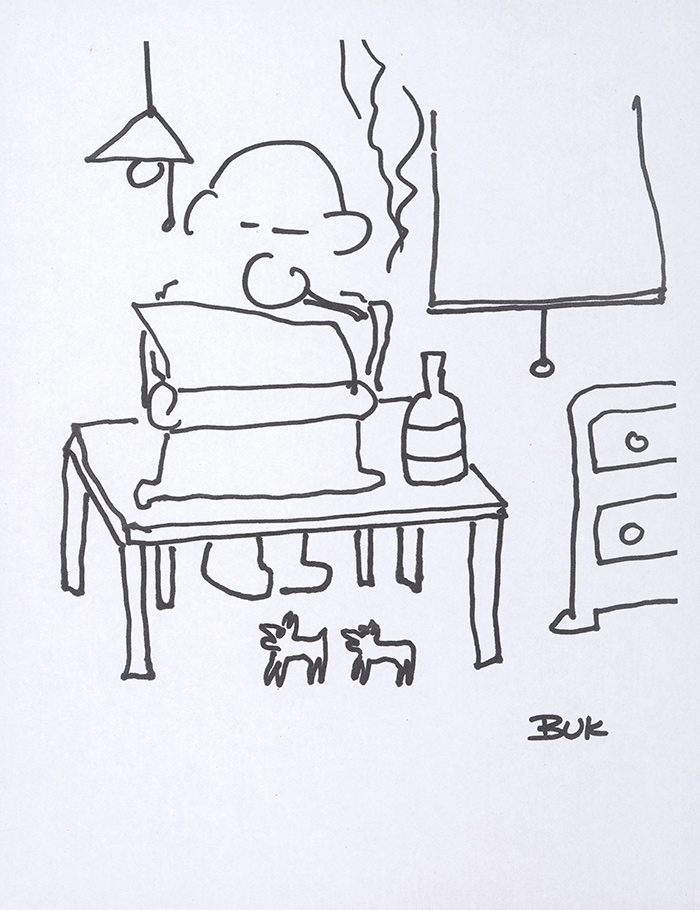

“All I need now is what I needed then: a desk lamp, the typer, the bottle, the radio, classical music, and this room on fire.” From “I am a Mole.” Self-portrait by Charles Bukowski. Undated. From the collection of Linda Lee Bukowski.

The Huntington began acquiring Bukowski’s papers in 2006, as a generous gift from his wife, Linda Lee Bukowski. Today the collection includes thousands of corrected typescripts of poetry, files of correspondence, rare editions of Bukowski’s works, and exceptionally rare issues of “little magazines” that published his earliest writings. The collection continues to grow, as Linda Bukowski transfers material to the Library on a regular basis.

In addition, the library has added a superb collection of closely related material, including photographer Michael Montfort’s images of Bukowski. In 2014, Montfort’s daughter, Daisy Montfort Spooler, donated his entire archive of thousands of photographs to the Library.

Montfort spent years documenting Bukowski, and his photographs appeared in such Bukowski classics as Shakespeare Never Did This, an account of the writer’s European book tour, as well as Horsemeat, a volume featuring Bukowski’s poems on horse racing and photographs of him at the racetrack. Montfort’s camera beautifully captured the rugged, ravaged face of the poet who sang of the downtrodden and their gritty lives of constant struggle.

By challenging the literary and cultural establishment, and by speaking for those on the edge, Bukowski forged a deep bond with his readers. That bond is as strong as ever, and his fans around the world will honor the poet and his words on August 16 in various ways—by visiting his gravesite, reading their favorite Bukowski poems and stories, and participating in festivals dedicated to his work.

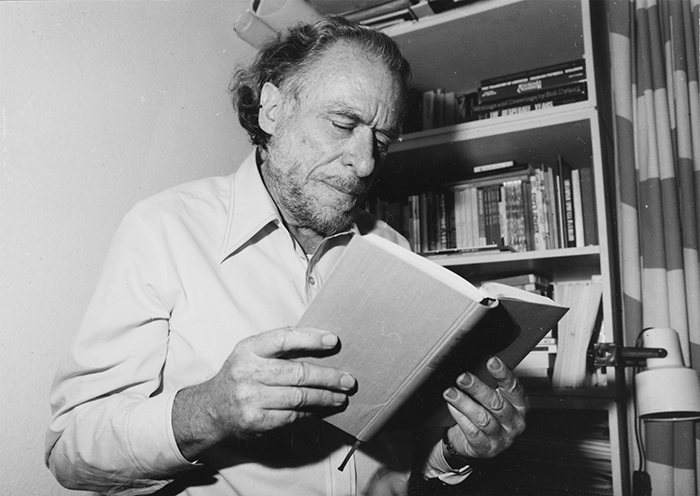

“I’m simple, I’m not profound. My genius stems from an interest in whores, working men, streetcar drivers—lonely, beaten-down people.” From “Faulkner, Hemingway, Mailer . . . And Now Bukowski?!” an interview with Ron Blunden, 1978. Photo by Eckharth Palutke, ca.1980. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Bukowski's novel Ham on Rye and his posthumous poetry collection What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire are available online from the Huntington Store.

Related content on Verso:

Bukowski on iTunes (Nov. 14, 2010)

Bukowski on the Inside (Oct. 8, 2010)

Sara S. “Sue” Hodson is curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington.