Posted on Wed., Jan. 17, 2018 by

William King (British, active mid to late 18th century), Granadilla Foliis Trilobatis, 1763, watercolor on vellum. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Have you ever found yourself fascinated by the intricate shapes and features of plants, or even taken the time to draw or photograph a beautiful flower that caught your eye? In the exhibition “In Pursuit of Flora: 18th-Century Botanical Drawings from The Huntington’s Art Collections,” you’ll find 16 drawings by a range of artists who were struck by the beauty of flowers. It’s on view in the Huntington Art Gallery’s Works on Paper Room through Feb. 19, 2018.

Some of these artists were among the most important botanical illustrators of their day; they made the images to disseminate knowledge about particular species of plants, often as reproductions in scientific publications. Several of the works, however, are the products of amateurs—in the 18th-century meaning of the word. Back then, being called an amateur did not imply any lack of artistic skill.

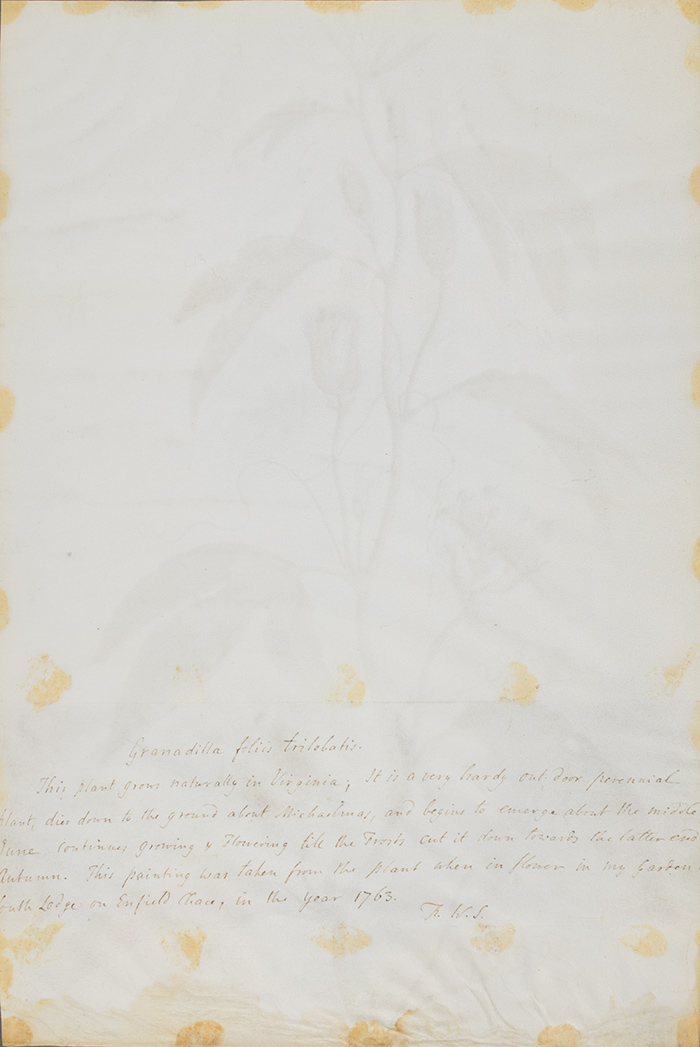

William King (British, active mid to late 18th century), Granadilla Foliis Trilobatis (verso, showing annotations by Thomas Skinner), 1763. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The word comes from the Latin “amare,” meaning to love. An amateur referred to someone who was passionate about a subject and practiced a skill without regard for monetary compensation. Most amateur artists of the period were members of the aristocracy or landed gentry—people with the wealth and leisure time to deeply follow their passions. Botany was another interest in which they could readily indulge.

Take, for example, several generations of botanical artists from the Conyers family of Essex. These women had ample opportunities to study a variety of plants on the family estate, called Copped Hall, known for its splendid garden. The family also owned properties on the Caribbean islands of Antigua and St. Kitts. These exotic locations may point to the origins of the Marvel of Peru, (Mirabilis jalapa), shown here by Matilda Conyers (1698–1793).

Matilda Conyers (British, 1698–1793), Marvel of Peru, 1767, watercolor and gouache on vellum. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Conyers may have taken drawing lessons from one of the most important botanical illustrators of the day, Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770), a collaborator of Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, as the family owned several of the artist’s works. Whether or not Matilda Conyers received instruction from Ehret himself, his influence is clearly evident in her drawing, which displays a careful rendering of variegated yellow and red flowers, and includes both open and closed buds to show as much botanical information as possible.

The drawings of English botanical illustrator William King (active mid to late 18th century) reflected the specimens he recorded from the garden of amateur botanist Thomas Skinner, who had collected several plants from the Americas, species that seemed decidedly exotic to his neighbors in suburban London. King’s intricate watercolor shows a passionflower (Passiflora), with its delicate twining tendrils. Skinner recorded his own observations about these exotic plants on the backs of King’s drawings. On one he describes the plant as “a very hardy out-door perennial” that “continues growing and flowering till the Frosts cut it down towards the latter end of Autumn.”

Peter Brown (British, active 1766–1791), Belladonna Amaryllis, ca. 1780, watercolor on vellum. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Artist Peter Brown (active 1766–1791) had been tutoring a number of aristocrats who engaged in botanical illustration before being appointed botanical painter to the Prince of Wales. His striking image of BelladonnaAmaryllis is similar to one that once formed part of an album of botanical illustrations made by Elizabeth Montagu (1741–1832), Duchess of Manchester. The presence of a number of Brown’s drawings inside the Duchess’s albums suggests that he may even have been her tutor.

Could the love of flowers expressed in these images encourage you to become an amateur artist yourself? Further inspiration is right outside the gallery in The Huntington’s extensive botanical gardens. Even if you are just as an observer, why not enjoy the beauty of these exquisitely rendered plants and flowers?

Georg Dionysius Ehret (German, 1708-1770), Climbing Lily, 1763, watercolor on vellum. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Melinda McCurdy is associate curator of British art at The Huntington.