The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Lusitania’s Anchor to the Past

Posted on Thu., May 7, 2015 by

Cunard Line produced this postcard-sized “souvenir log” (1908) depicting the "Lusitania" departing New York Harbor, with the Statue of Liberty in the background. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A hundred years ago today, on May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British ocean liner RMS "Lusitania." Of the 1,962 passengers and crew on board, more than 1,100 lost their lives, including 128 Americans. It was a turning point in America’s position of neutrality in the face of increasing German aggression. Less than two years later, on April 6, 1917, the U.S. Congress would vote to declare war on Germany.

Some of The Huntington’s most colorful and curious items about World War I—including items related to the "Lusitania"—come from the Kemble Maritime Ephemera Collection. A treasure trove of 24,000 objects covering the period from 1855 to 1990, the collection includes ship histories, travel brochures, schedules, passenger lists, menus, posters, flyers, and other ephemera from some of the most prominent shipping companies of the 20th century. This includes Cunard, the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, and the White Star Line.

As a Ph.D. student at Berkeley in the 1930s, maritime historian John Haskell Kemble wrote his thesis on The Pacific Mail Steamship Company, the 19th-century boat service that carried passengers from the Isthmus of Panama to San Francisco before the Panama Canal was built. He published the work in 1943 as The Panama Route, 1848–1869. Kemble’s fascination with maritime history continued throughout his life, and he eventually filled two homes with his assorted ephemera. In the 1960s, he started donating much of his collection to The Huntington.

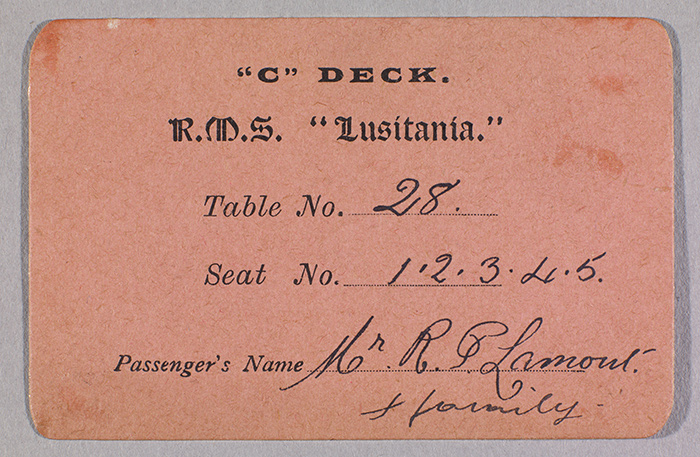

A place card (1914) from the "Lusitania" indicates where a passenger and his four family members should sit. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

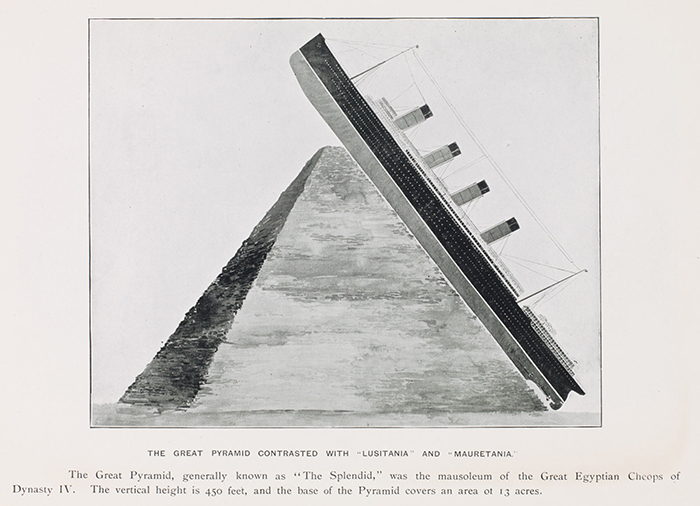

The "Lusitania" figures in at least a dozen items in the collection. In brochures, a deck plan, a postcard, and menus, we see a large and luxurious ocean liner equipped to satisfy the most demanding travelers. A wonderful brochure compares the size of the "Lusitania" to famous landmarks, such as the Great Pyramid of Giza and the U.S. Capitol.

There are also somber items reflecting the fateful sinking of the great ship. In a page from Lloyd’s Register of Shipping for the year 1915–1916, the entry for the "Lusitania" has the words “Sunk (War Loss)” stamped beside it.

The sinking of the "Lusitania" off the coast of Ireland shocked Americans. However, it wasn’t entirely unexpected. In early May 1915, several New York newspapers published an announcement from the Imperial German Embassy in Washington, D.C., warning Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones that they did so at their own risk. The warning was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the "Lusitania," departing New York for Liverpool, England.

Travel brochures like this one (ca. 1907) vaunted the grandness of ocean liners such as the "Lusitania." The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The British Admiralty had warned the "Lusitania" to take simple evasive action, such as zigzagging to confuse U-boats plotting the vessel’s course. Captain William Thomas Turner seems to have ignored those recommendations, believing his vessel fast enough to outrun a German submarine.

By lunchtime on May 7, the morning fog shielding the "Lusitania" had burned off. At 2:10 pm, under clear skies and in calm waters, a German U-boat torpedoed the 32,000-ton ship. A larger explosion soon followed. The ship sank in less than 20 minutes. It was later revealed that the "Lusitania" was carrying war munitions for Britain, which the Germans cited as further justification for the attack.

I have an object related to the sinking of the "Lusitania" from my own collection, for I too am fascinated by maritime history. It is a crude copy of an actual medallion created by German artist Karl X. Goetz (1875–1950) and meant as a political statement on the perfidy of the Allies. He depicted the sinking of the "Lusitania" on the front, her decks loaded with armaments. On the reverse, he shows people buying tickets from Death, with the German Ambassador warning them not to go. The British seized upon this medal as proof of German pride in, and approval of, the sinking of the ship. London department store owner Harry Gordon Selfridge produced 300,000 copies of the medallion and sold them in a little box with an image of the "Lusitania" on its cover.

A copy of a medallion (1916) designed in Germany, showing passengers of the "Lusitania" buying tickets from Death. From the author's collection.

The sinking of the "Lusitania" was a wrenching incident that figured prominently in the lead up to World War I, yet after the war, it largely slipped out of the public conscience. That is changing as centennial commemorations of the Great War bring renewed focus to this tragic event. Erik Larson’s new bestselling book, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, revisits the gripping story in fine style.

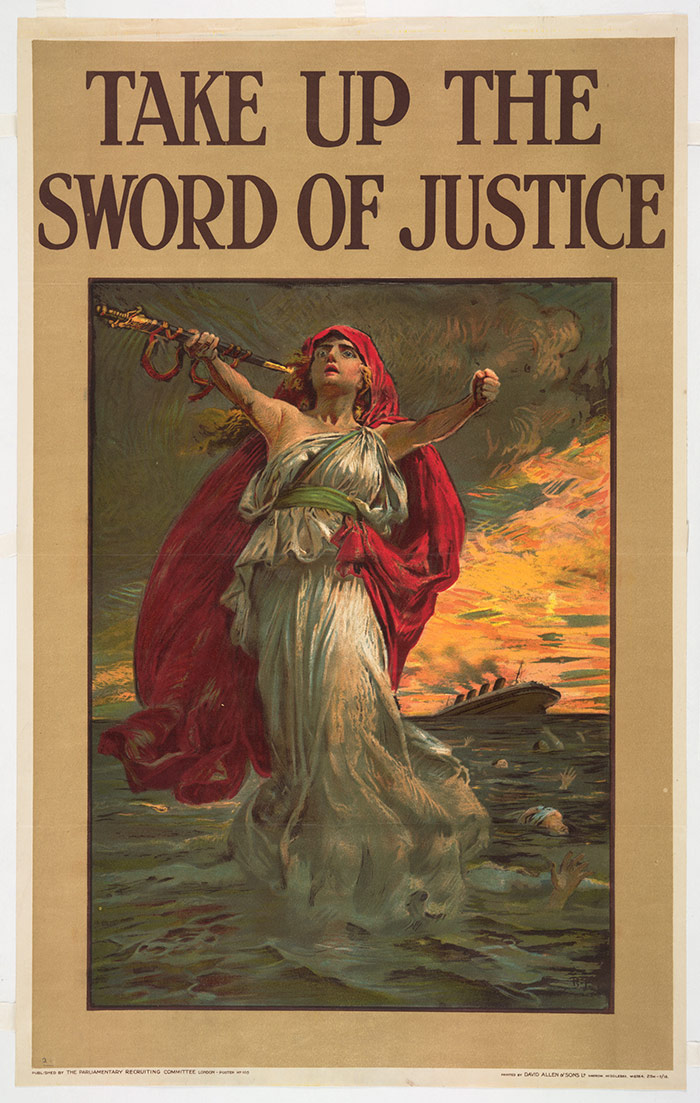

Late last year, The Huntington organized the exhibition “Your Country Calls! Posters of the First World War.” One poster showed the allegorical figure of Britannia rising from the sea holding a sword in her outstretched hand. Bodies float in the water, and the "Lusitania" can be seen sinking in the background. The title urges the viewer to “Take up the Sword of Justice.”

Unlike the unfortunate passengers of the "Lusitania," John Haskell Kemble, whose maritime collection preserves some of the great ship's ephemera, died peacefully in his sleep on a deck chair aboard S.S. "Canberra" in February 1990, sailing between New Zealand and Australia on his fourth round-the-world cruise.

“Take Up the Sword of Justice,” 1915, Bernard Partridge (1861-1945), color lithograph, 40 1/16 x 25 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Mario Einaudi is the Kemble Digital Projects Librarian at The Huntington.