The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Maps that Scholars (and Goonies) Treasure

Posted on Tue., May 31, 2016 by

This chart includes one of the earliest depictions of the New World. King-Hamy portolan chart, Italy, ca. 1502 (HM 45). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the early 1980s, Mary Robertson, then chief curator of manuscripts, had an unusual meeting with a film production designer. Robertson was used to talking with people about the wonders and mysteries within The Huntington’s vast and renowned collections. But this man had an odd request—he wanted to see real pirate maps because he was designing one for a movie he was working on. The film’s working title sounded like gibberish: The Goonies.

Robertson spent much of the day with this man, showing him examples from The Huntington’s 16th- and 17th-century manuscript map collections. She talked about the aesthetics of early modern cartography to help give him a sense of what an old pirate map might look like. At one point, the designer described his vision of the pirate map’s exploding in a great “poof!” Robertson explained that old maps were drawn on parchment, which is made from animal skin, and that they would not explode. “Parchment melts,” she immediately responded. “It would never poof!” She even took him to The Huntington’s conservation laboratory to prove it with a modern parchment sample. There went that idea!

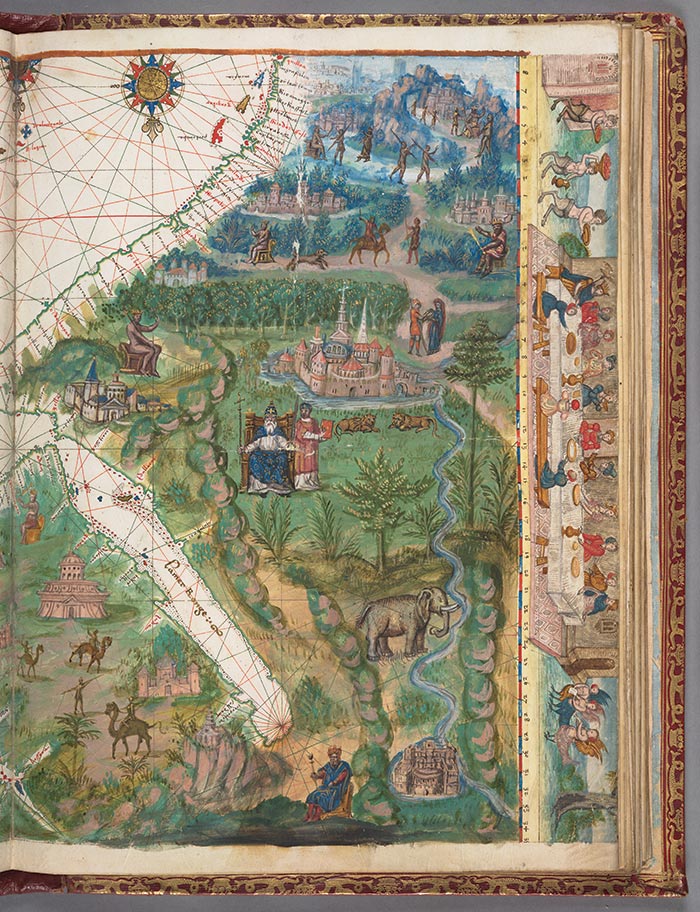

All the charts of the Vallard Atlas are oriented to the south. The large elongated body of water is the Red Sea. Follow the coastline to the right and you’ll see the Horn of Africa and then further on, the island of Zanzibar, across from present-day Tanzania. Vallard Atlas, France, 1547, Chart 4 (HM 29). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The designer thanked Robertson for her time and headed back to Hollywood. The rest is film history, as The Goonies went on to become a cult classic. In the film, a treasure map once used by the mythical pirate One-Eyed Willy leads a band of kids on the adventure of a lifetime.

The Huntington’s manuscript map collections have led many scholars on equally thrilling adventures. The Huntington holds about 30 manuscript portolans—navigational charts and maps created primarily in the 16th century. The term “portolan” comes from porto, the Italian word for “harbor.” Portolans provided compass directions and estimated distances between one port and another. Most were made by Portuguese cartographers or are copies of their maps, as Portugal was the birthplace of the European maritime revolution.

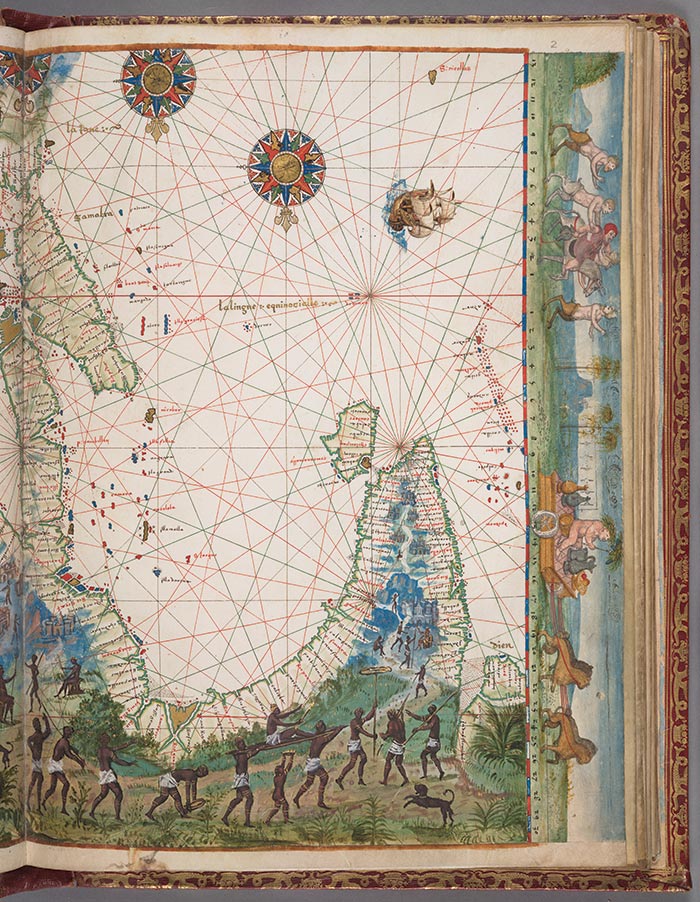

Again orientated south, this section of the Vallard Atlas shows the island of Sumatra at the upper left and intricate scenes of indigenous people. Vallard Atlas, France, 1547, Chart 2 (HM 29). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of The Huntington’s most important examples is the King-Hamyportolan, consisting of a single folio and showing one of the earliest depictions of the New World. The 1502 document shows Greenland, Newfoundland, the northern coast of South America, and the east coast of Brazil. We see both America and Asia, but the relationship between the two continents remains ambiguous. This portolan was produced either in Portugal or in Italy from Portuguese sources, possibly by the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. (The portolan’s name refers to its provenance, as it was owned by Richard King and then Dr. Jules Théodore Ernest Hamy.)

While the primary function of a portolan was to guide European sailors, merchants, and buccaneers in their exploits on the high seas, the charts also provide critical insights into how Europeans viewed the world. They can be elaborately decorated, whimsical, and fantastical as they identify known port cities along continental coastlines. Their creators used lore, travel logs, and rumor to express Europeans’ beliefs about what lay in the continents’ interiors.

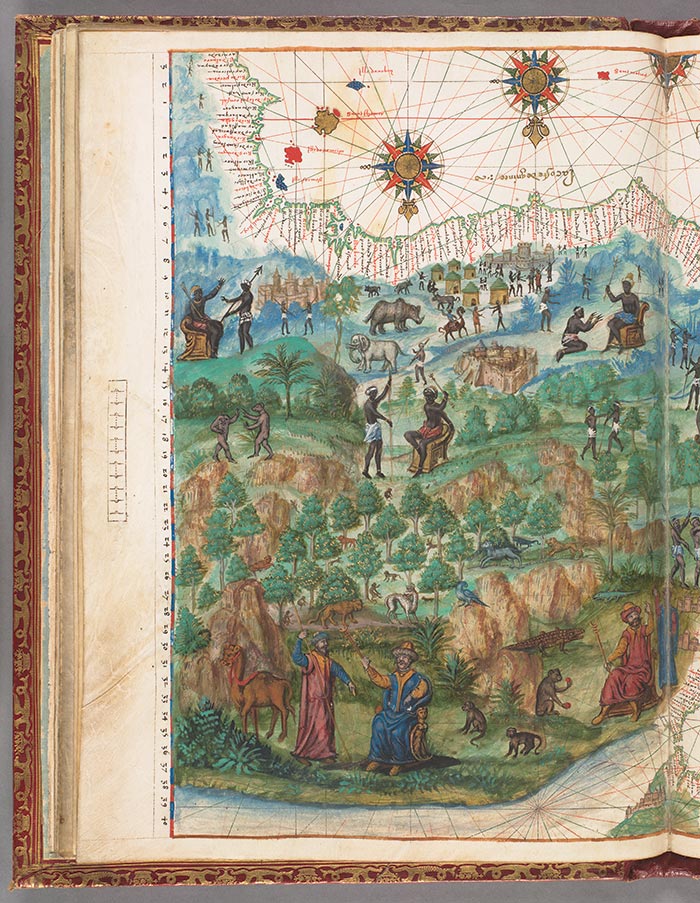

This part of the portolan depicts a stretch of the African coastline and a European view of what the people of Africa might look like. Vallard Atlas, France, 1547, Chart 7 (HM 29). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Paintings revealed castles, religious houses, and exotic animals—such as elephants, lions, camels, and even sea monsters. They also depicted kings, merchants, soldiers, laborers, and fictional scenes of everyday interactions.

One of The Huntington’s most artistically celebrated portolans is the Vallard Atlas (named after its first owner, Nicolas Vallard), which dates from 1547. This elaborately decorated atlas was made in Dieppe, a town in northern France known for its cartographic school. It comprises 15 navigational charts, including some of the first European renderings of Australia, the East Indies, and parts of Africa and Asia.

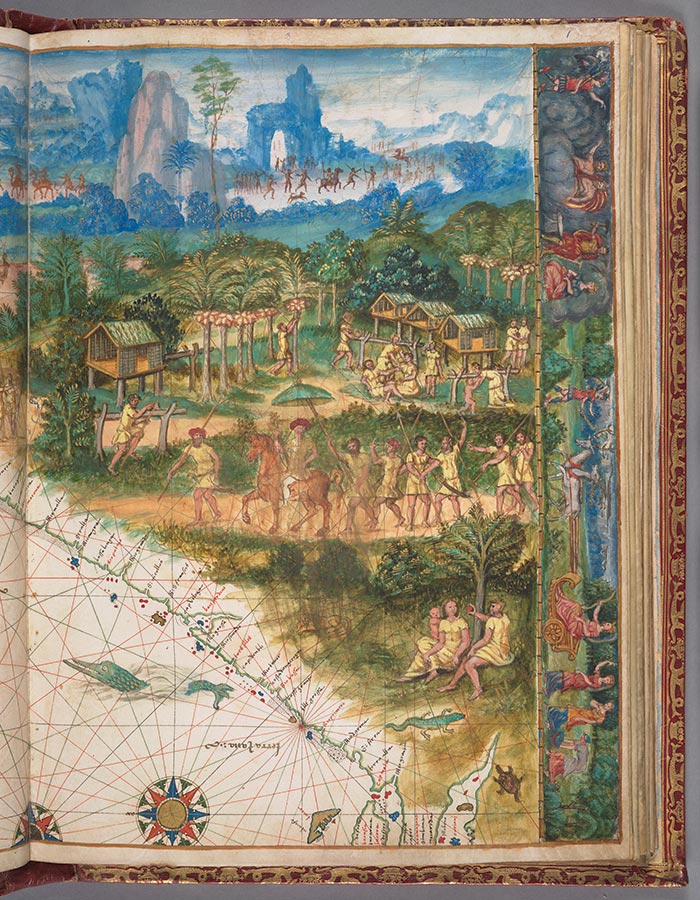

The vibrant imagery in this portolan makes it an invaluable source for studying racial and ethnic perceptions in early modern Europe. One chart in the Vallard Atlas depicting “La Java” (the coast of Australia) displays intricate scenes of indigenous people.

Scholars will continue to explore portolans for their complex and dynamic insights into the early modern European mind. In The Goonies, the map led to treasure, but for scholars, these maps are the treasure!

The coastline shown here is referred to as “La Java.” In actuality, it is the coast of Australia, depicted 200 years before Captain Cook “discovered” it. Vallard Atlas, France, 1547, Chart 1 (HM 29). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Smoothing the Path (May 13, 2014)

Vanessa Wilkie is the William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval and British Historical Manuscripts.