The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Mean Streets of L.A.

Posted on Thu., May 5, 2011 by

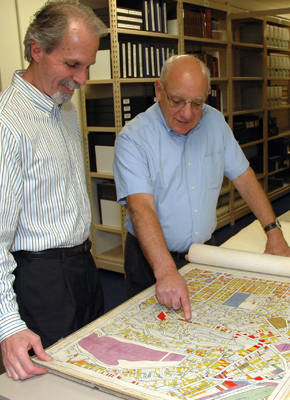

Alan Jutzi (right), chief curator of rare books, and colleague David Mihaly look at one of the L.A. city maps used by researchers developing the video game project. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

If you love murder, mayhem, and mapmaking—this story's for you!

Over the years, The Huntington's collections have lent themselves to a wide variety of research projects: scholarly books, journal articles, doctoral dissertations, films, costume design, even archeology. Now we can add something new to that list: video game design.

On May 17, Rockstar Games will launch a new video game called L.A. Noire, jointly developed with the Australia-based company Team Bondi. An action-packed detective thriller set in the mean streets of Los Angeles in 1947, it's already generating a great deal of advance buzz. But you don't need to be a gamer to get excited about one of L.A. Noire's signature features: the designers have recreated an authentic virtual Los Angeles, starting literally from the ground up.

As reported in a recent story in the Los Angeles Times, production designer Simon Wood and his Team Bondi colleagues used street maps from The Huntington's holdings to lay the foundation for their vintage cityscape. Dating from the mid-1930s, these detailed land-use maps were commissioned by the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, a Depression-era program to create jobs—in this case, for surveyors, draftsmen, and urban planners.

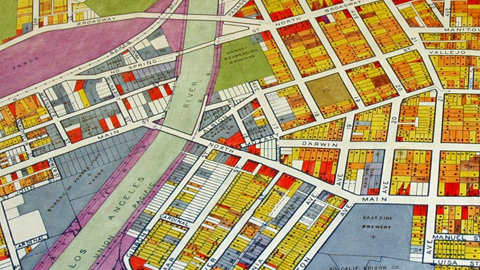

On a recent afternoon, Alan Jutzi, The Huntington's chief curator of rare books, took one of the large, bound volumes off a library shelf and opened it to a street grid from the Elysian Park area. He pointed out how each parcel of land was color coded by use: yellow for multi-family residences, red for commercial businesses, gray for industrial sites, purple for utilities, green for parks and agricultural areas. A numerical key provided another layer of detail, recording what type of businesses, from bakeries to service stations, were located on each lot.

A close-up view shows color-coded parcels of land in the area northeast of downtown, where Broadway crosses the Los Angeles River. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

The game designers digitally stitched together some 300 of these maps, creating a working template that captured the broad sprawl of the city, from the Sunset Strip to East L.A. and beyond. They then added dimension and detail with the aid of topographical information from the U.S. Geological Survey, aerial photographs from the era from UCLA's Spence Air Photos collection, and thousands of period photos. The final result is a gritty, three-dimensional virtual city where gamers will be able to immerse themselves in a realistic world of noir. Philip Marlowe himself would feel right at home.

"It's mind-boggling how much effort these guys went to," says Jutzi, reflecting on the years of painstaking effort involved. That comment could apply to both the video game team and the original mapmakers. The extensive street-level detail gave the designers the historical information they needed to digitally create the game's realism. The WPA draftsmen would be proud!

A botanist, however, might raise an eyebrow at one minor point in which in the virtual world of L.A. Noire strays from historical accuracy: the designers opted to depict L.A.'s iconic palm trees, which were still quite short in the 1940s, at a more familiar modern-day height.

But let's not quibble about details.

Lisa Blackburn is communications coordinator at The Huntington.