The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Medicine by Moonlight

Posted on Wed., May 30, 2018 by

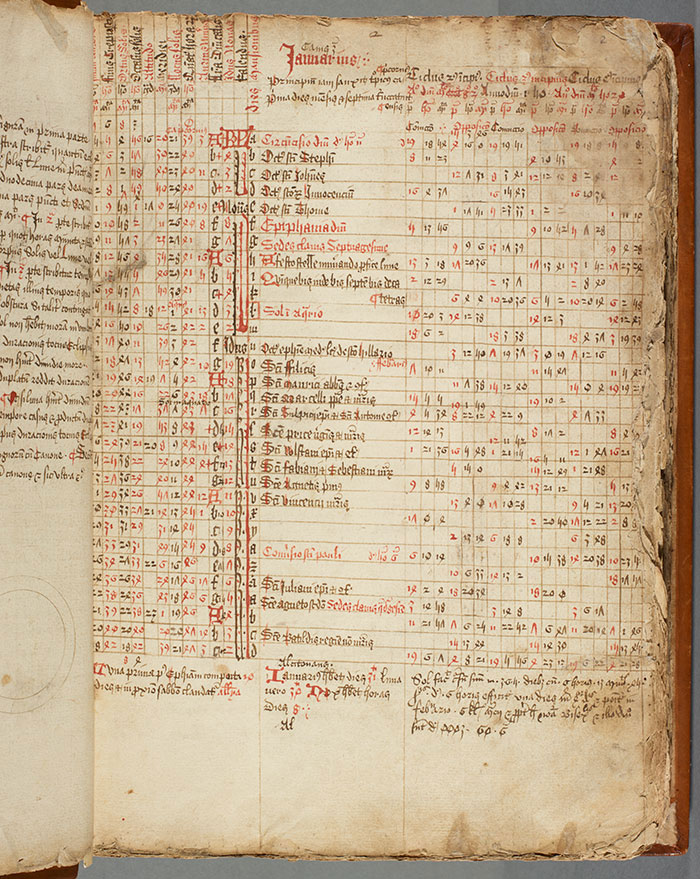

This late 15th-century manuscript, an astrological and medical compilation, starts off with a detailed and complete calendar of the year, with saints’ feast days (“red letter days”) highlighted in red. Shown here is the month of January. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In The Huntington’s collections, there is a late 15th-century manuscript whose title in the Library catalog is “Astrological and Medical Compilation.” Many medieval manuscripts are “compiled” in the sense that they frequently collect heterogeneous materials—from different genres of writing, on different topics, and even in several different languages—within a single volume. Sometimes, we can detect a reason that these materials were brought together (a collection of devotional materials, for instance), but frequently we can’t.

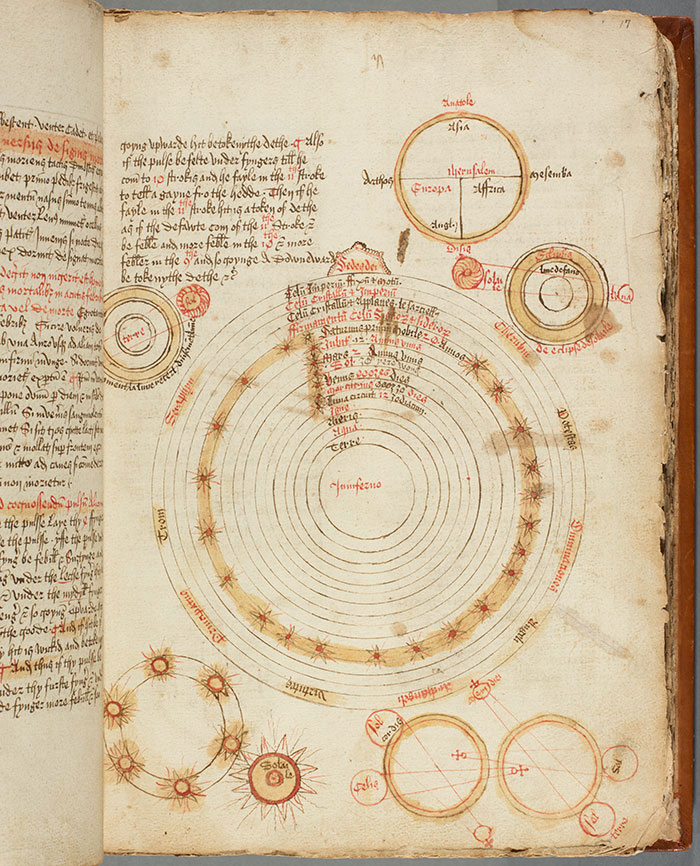

At first glance, it might seem that this manuscript collects unrelated materials. It starts with a detailed and complete calendar of the year, with saints’ feast days (“red letter days”) highlighted in red. The calendar is followed by information on the moveable feasts, and then an astrological table. Elsewhere in the manuscript there is a world map, information on the occurrence of eclipses, and other astrological material on the movements of the planets and the prediction of astronomical events.

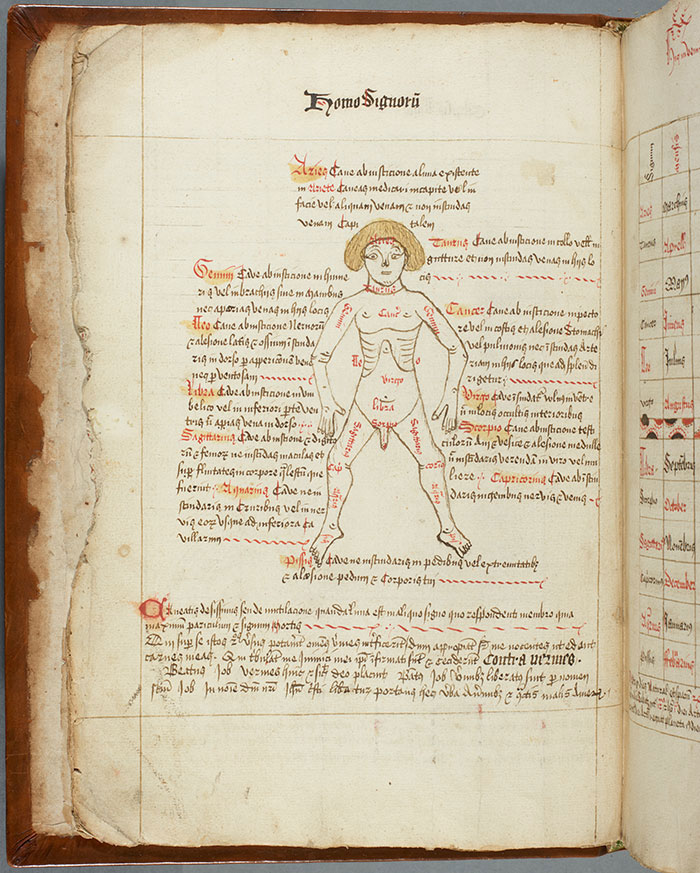

Different parts of the manuscript’s “zodiac man” (found on folio 12 verso) are labeled with the signs of the zodiac to which that part corresponds: Taurus for the neck, for example, and Virgo for the belly. This information was important in making decisions about medical treatment. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

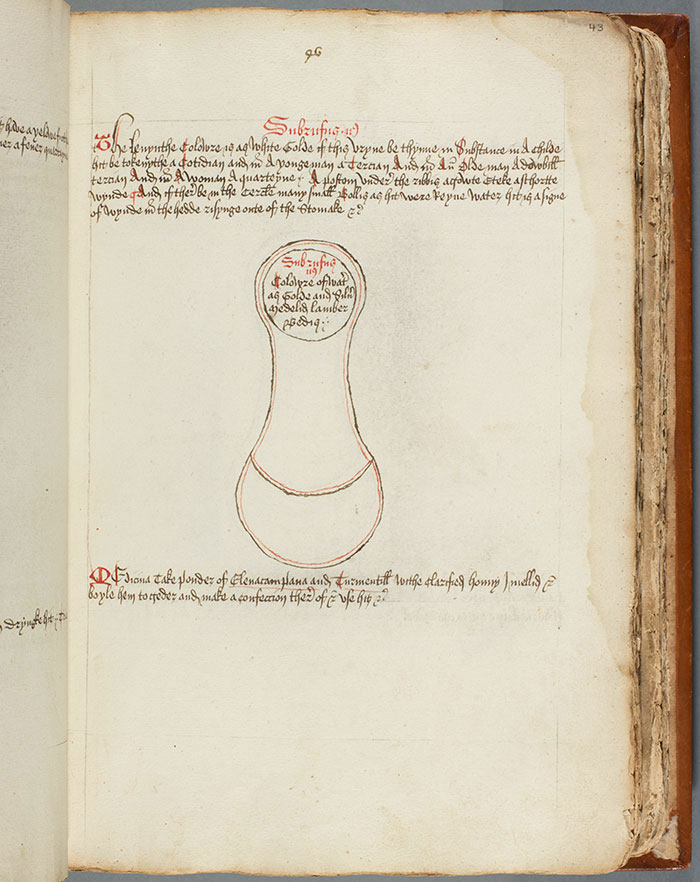

On the other hand, this manuscript also features diagrams of the human body for therapeutic bloodletting, hundreds of medical recipes, drawings to help doctors diagnose disease from the appearance of urine, and excerpts from treatises that cite the great physicians Hippocrates and Galen. One set of texts clearly conforms to what we think of today as medicine, and the other set to astronomical and astrological knowledge: a different science.

However, from a medieval point of view, these materials are not as unrelated as they might seem. When I took my students to view this manuscript on a class visit, I asked them: why would you need a calendar in a medical manuscript? Prompted by our discussions in class on the nature of medieval medical knowledge, they answered correctly: to treat people in the Middle Ages, you had to understand the whole universe.

On this page (folio 17 recto), you find a world map, celestial and planetary diagrams, and diagrams of eclipses. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

This is a bit of an exaggeration, but only a bit. The reason that the material on ways of keeping track of time, and celestial movements, appears alongside medical advice in this manuscript is that these celestial movements affected how medieval physicians treated their patients. The human body was seen as a reflection of the universe, and changes in the celestial bodies were thought to bring about corresponding changes within the human body.

Furthermore, just as the regions of the earth could be divided along the 12 signs of the zodiac, with different signs affecting the characteristics of different regions, the body of a man could be divided in the same way. You can see this idea represented in the manuscript’s “zodiac man.” Different parts of his body are labeled with the signs of the zodiac to which that part corresponds: Leo to the heart, for example, and Virgo for the belly. This information was important in making decisions about treatment. When bloodletting, for instance, depending on the “sign” that was dominant, the physician would remove blood from a different site on the body.

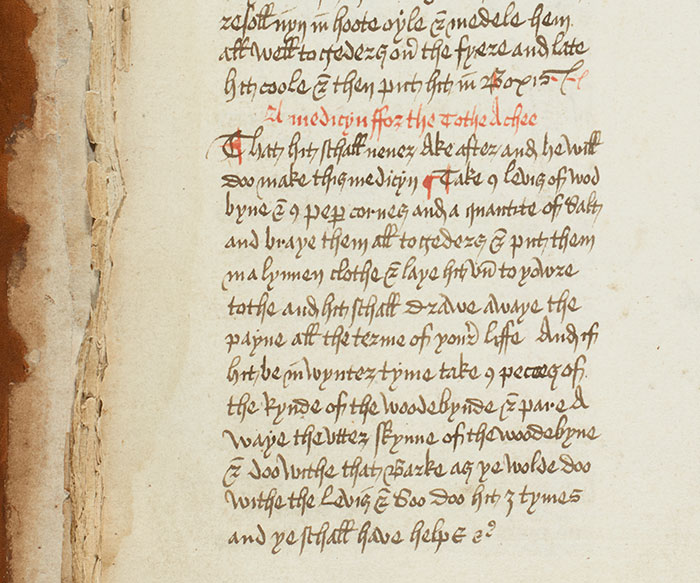

A medical recipe for toothache appears on this page (folio 24 verso). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As the recipes in this book demonstrate, to be a physician in the Middle Ages, you also needed to be proficient in other areas of specialized knowledge. You not only had to understand the movements of the heavens to know when and how to treat, how to perform phlebotomy, and when to do it. You also needed a good knowledge of botanical materials, which had to be not only accurately identified and located, but also sometimes needed to be harvested under specific astrological conditions to have the right effect in medical recipes. You had to know the specific properties of different stones, which were thought to have protective or healing properties; how to recognize and assess small variations in color and quality in urine samples, a noninvasive diagnostic method (which, in a different version, is still in use today); and you also needed to have a reserve of prayers, protective charms, and incantations. Finally, as this manuscript also demonstrates, you might need to be pretty good with languages, too. This particular manuscript is written in English, Latin, and French—and the languages sometimes switch on the same page.

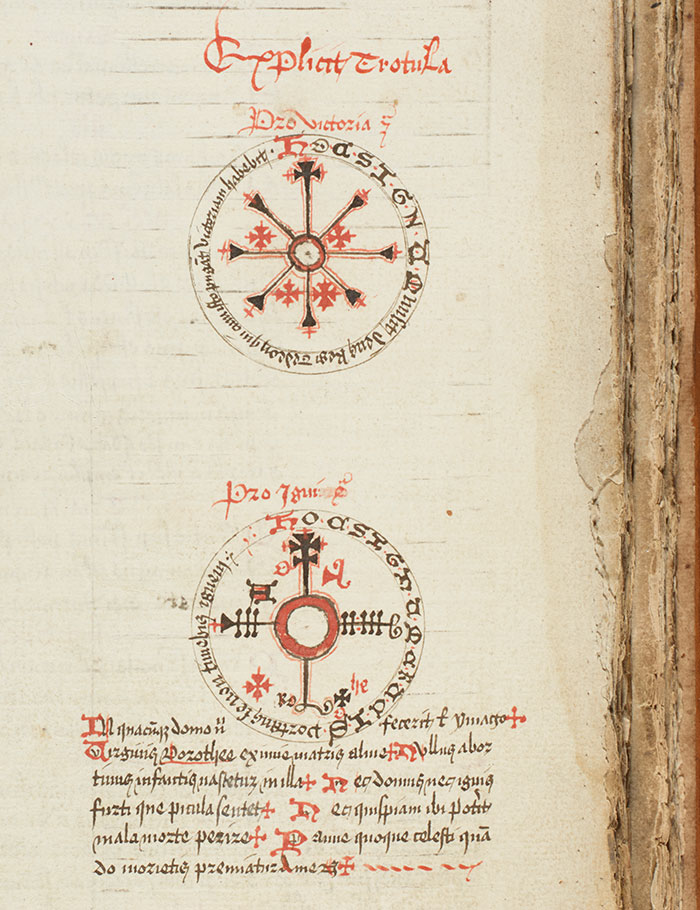

Among the medical practices found in this medieval manuscript are such charms as the ones found on this page (folio 34 recto). These specific charms state that the person who wears or carries them will have victory in battle (the top one) and will not be afraid of fire (the bottom one). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Among the medical practices found in this medieval manuscript are such charms as the ones found on this page (folio 34 recto). These specific charms state that the person who wears or carries them will have victory in battle (the top one) and will not be afraid of fire (the bottom one). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Today many of the medical practices that we find in medieval texts would fall into the category of occult beliefs, and we might even call the charms and incantations “magic.” On the other hand, this textual collection, and other manuscripts like it, also demonstrate the vast amount of knowledge and care that went into these practices. Although we might not believe in their efficacy today, these methods required a high degree of expertise in a number of heterogeneous fields of scientific inquiry. Some of these fields—botany, especially—have continued to be essential to modern medical innovation. In planetary sciences, the detailed collection of observational data for astrological tables, like the ones in this manuscript, would soon be taken up by such early modern scientists as Brahe, Copernicus, and Kepler to revolutionize our understanding of our place among the stars. And indeed, sometimes even medieval prescriptions can still surprise us. Recently, researchers looking for novel approaches to treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections found that a medieval recipe for wound salve was surprisingly effective.

On this page (folio 43 recto) is an illustration of a urine bottle. Medieval doctors would recognize and assess small variations in color and quality in urine samples—a noninvasive diagnostic method which, in a different version, is still in use today. However, in this particular manuscript, the bottles were never colored in to depict the urine samples. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

This specific manuscript was certainly the possession of a learned individual. Medieval medical practitioners, of course, ranged in educational level and in skill, and the text shouldn’t be understood as a blueprint for all medieval medical practice. But it’s an excellent demonstration of the depth and breadth of what constituted medical knowledge in the Middle Ages, a compendium of scientific mastery not only of the human body but of celestial bodies, natural philosophy, and the measurement of time.

If you’d like some medieval advice on when you might want to schedule your next doctor’s appointment, then you’ll be happy to learn that this manuscript has been completely digitized. You can see it in its entirety at the Huntington Digital Library.

Leah Klement is a Caltech-Huntington Humanities Collaborations postdoctoral instructor and 2016–18 long-term fellow at The Huntington.