The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Miki Hayakawa: Painting in Place

Posted on Tue., May 24, 2022 by

Miki Hayakawa, From My Window, 1935, oil on canvas, 28 × 28 in. Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo by Aric Allen.

Miki Hayakawa’s From My Window—on loan from the collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra in The Huntington’s Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art—captures a specific place and time. Hayakawa (1899–1953) painted this view from her home near the northeastern corner of San Francisco, just a few blocks from Telegraph Hill, in 1935. At the center of the canvas is a vase filled to its brim with bright pink blooms, some drooping and some still waiting to open. The vase sits on a vibrantly striped tablecloth, near a checkered brown curtain pulled back to reveal the buildings dotting the hill—at the top of which stands the imposing Coit Tower. A still life that denotes an exact dot on the map, this painting is a window into the movements and displacements of Hayakawa’s life as an Asian American woman and modernist painter in pre–World War II California.

An immigrant artist who worked in California and later in New Mexico, Hayakawa was born in Hokkaido, Japan, and moved when she was 9 with her mother to join her father, a pastor, in Oakland, California. In 1908, when Hayakawa arrived in the United States, there were many legal restrictions on Asian immigration and naturalization: The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place (restricting entry of Chinese people into the United States); many Asian immigrants were not eligible to become U.S. citizens; and the expanded Immigration Act of 1917, which also excluded other people of Asian descent, would pass within a decade of her arrival.

Hayakawa forged her artistic identity by the bay. By the time she was a teenager, Hayakawa knew she wanted to be an artist. She went on to train at the School of the California Guild of Arts and Crafts in nearby Berkeley and across the bay at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco in the 1920s. During the 1920s and 1930s, Hayakawa took part in an active artistic community in San Francisco that included Chinese American painter Yun Gee and the artist couple Matsusaburo and Hisako Hibi. Hayakawa’s paintings, shown widely throughout California, were well reviewed by critics and respected by her peers.

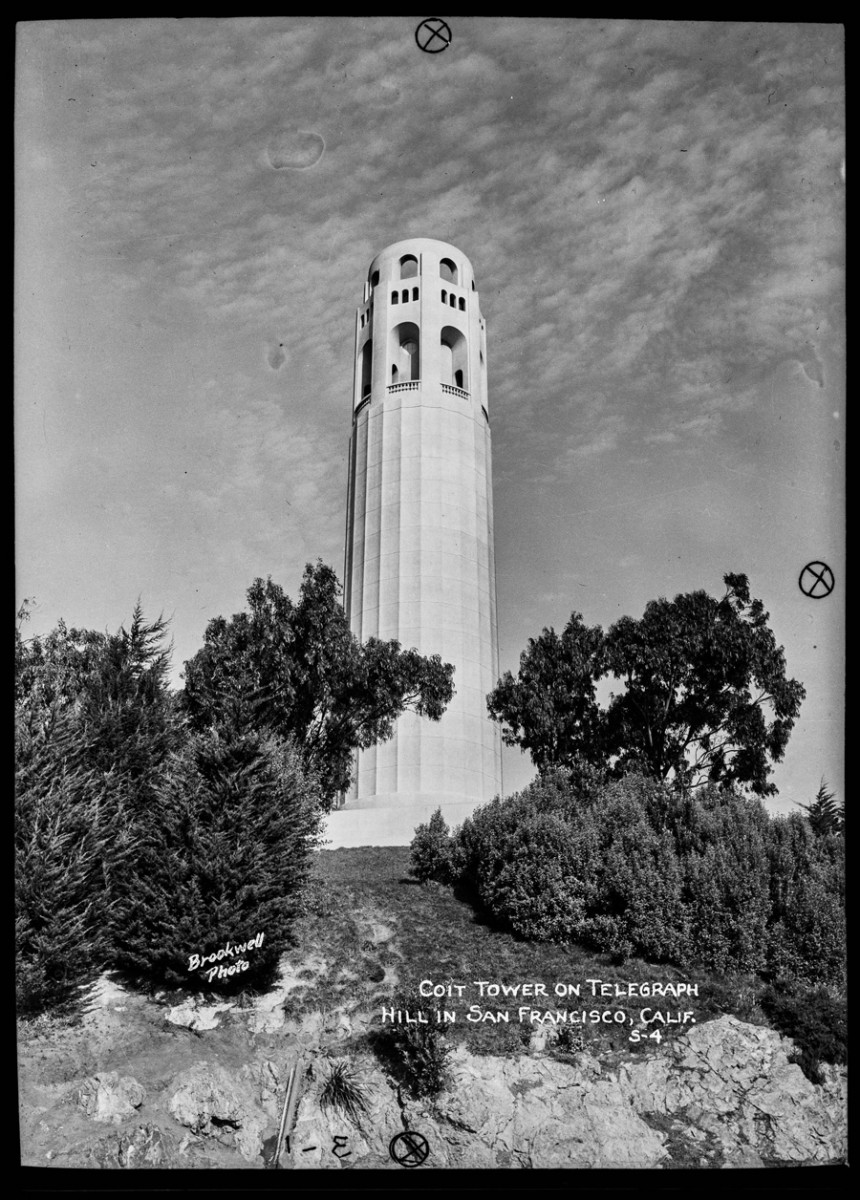

Brookwell Photo, Coit Tower on Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, Calif., not before 1933. Ernest Marquez Photograph Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As art historian ShiPu Wang discussed in his book The Other American Moderns (Penn State University Press, 2017), Hayakawa’s depiction of the newly erected Coit Tower in From My Window seems to reference the building’s radical mural program. A bright white beacon visible from the bay and around the city, the concrete tower was completed in 1933—only two years before Hayakawa pictured it. A vintage image from The Huntington’s Ernest Marquez Photograph Collection also shows the tower that year. In 1934, 26 American artists were commissioned to create a series of murals and frescos on the interior walls of the structure through the New Deal–funded Public Works of Art Project—however, Hayakawa was not one of them. As Wang suggests, Hayakawa’s From My Window is a view of the city’s artistic community, as well as its progressive politics and artistic rivalries.

The Coit Tower murals, with their social realist style and progressive subject matter, recall such Mexican muralists as Diego Rivera, whose work deeply influenced artists in America in the 1930s. On the theme of “Life in California,” the murals depict San Francisco neighborhoods near the tower, as in Russian American artist Victor Arnautoff’s ground-floor mural City Life, which captures a bustling and chaotic scene at the corner of Montgomery and Washington streets—less than a mile away from where Hayakawa painted her view of nearby Telegraph Hill. Hayakawa’s rounded forms and solid masses speak the language of this kind of Works Progress Administration–era art.

Victor Arnautoff, City Life mural on the ground floor of Coit Tower, 1934. Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Yet Hayakawa’s From My Window is more private, domestic, and intimate than the civically charged, public-facing murals inside Coit Tower. Like so many still life paintings, it seems to reveal the interior life of the artist precisely due to the lack of a figure. Her lived experience is felt in her contemplative view of her city from the vantage of her windowsill, where she cultivates a relatable row of house plants and a vase of cut flowers, perhaps purchased at a flower shop in adjacent Little Italy or Chinatown.

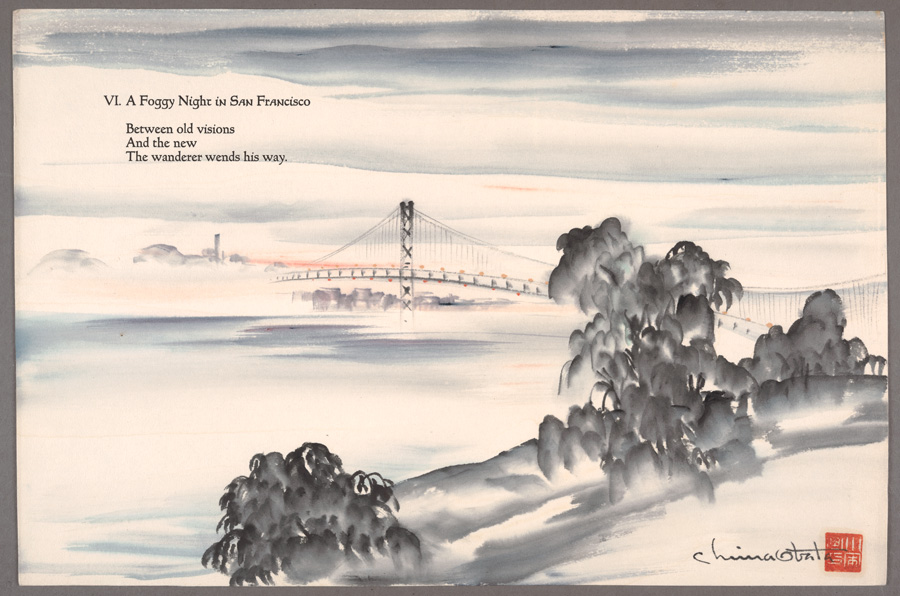

Hayakawa’s view of San Francisco relates to a work in our Library collections by another Japanese American modernist painter working in 1930s California. Chiura Obata’s 1937 brush painting accompanies his poem titled “A Foggy Night in San Francisco,” from a series of watercolor and sumi ink paintings and poems titled From the Sierra to the Sea. Hayakawa and Obata, a landscape painter and art faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley, ran in similar artistic circles and exhibited together. In “A Foggy Night in San Francisco,” Obata presents a view similar to the one Hayakawa depicts but from the vantage point of the East Bay, looking toward the Bay Bridge (built in 1936) and the San Francisco skyline (including a distant Coit Tower).

Chiura Obata, “VI. A Foggy Night in San Francisco” in From the Sierra to the Sea, 11 original brush drawings of California subjects . . . each accompanied by a translation from the artist’s poetry (Berkeley: Archetyne Press, 1937). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As I write this post during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I reflect that I’m about the same age that Hayakawa was when she painted From My Window. In the quietude of this picture, I see the resilience of Asian American artists who continued to collaborate, produce work, and show widely despite the systematic and legal discrimination they faced—in Hayakawa’s case, as a Japanese American woman in the Asian Exclusion period and, later in her life, during the internment period. While Hayakawa herself was not interned, her parents were detained at the Tanforan Relocation Center in San Bruno, California, and later at the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. During the internment period, Hayakawa relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

With this in mind, From My Window recalls a pre-internment California—seven years before President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the racial profiling, detainment, and forced internment of Americans of Japanese descent on the West Coast during World War II. Pushed out of her home state, Hayakawa lived in Santa Fe for the rest of her life and continued to paint—presenting a solo exhibition of her works in 1944. When she died nine years later, she left behind a large body of captivating paintings, including her sensitively rendered portraits of women and sitters of color. In the past decade, attention to her work has increased (thanks to art historians like Wang), and she is beginning to be recognized as an artist who both represented and transcended her time.

Miki Hayakawa, From My Window, 1935, oil on canvas, 28 × 28 in. Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo by Aric Allen.

Yinshi Lerman-Tan is the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington.