The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

For Neophiles, Aesthetes, and People Who Like to Eat

Posted on Thu., Feb. 25, 2016 by

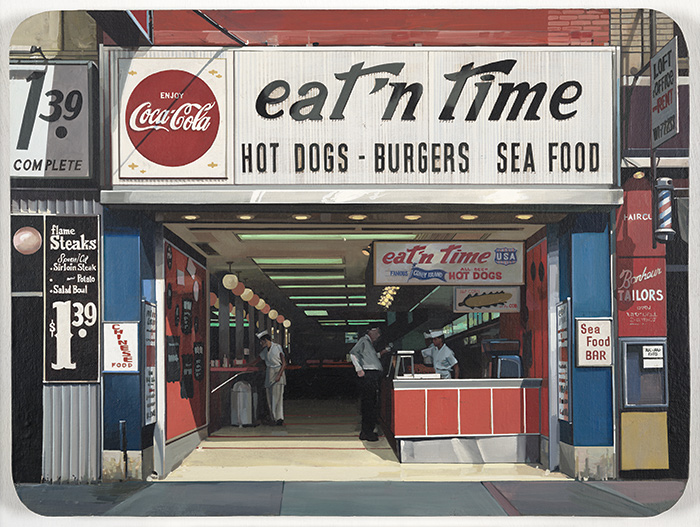

Richard Estes (b. 1932), eat'n time, 1968-1969, oil on Masonite, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Laurence and Carol Pretty © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York.

Surprise! There are 11 new acquisitions on view in one room in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art right now. That’s great news for neophiles, and even greater news for fans of representational art from the mid-20th century. Plus, there are stylish modern silver and ceramic works. If you’ve been craving a peek at the latest expansion to the Scott Galleries (due to open in October), then here’s a visual snack to tide you over.

For starters, in addition to the new works announced last spring (among them a fascinating Milton Avery), the installation boasts a tasty example of photorealism. Richard Estes painted eat'n time—and made the groovy frame—in 1969.

Paul Wonner (1920–2008), Dutch Still Life with Cyclamen, 1980, oil on canvas 68 x 72 in. (172.7 x 182.9 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Harlyne Norris © Social Profit Network.

Paul Wonner (1920–2008), Dutch Still Life with Cyclamen, 1980, oil on canvas 68 x 72 in. (172.7 x 182.9 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Harlyne Norris © Social Profit Network.“We’d long wished for a strong example of photorealism to complement our other mid-20th-century works,” says Jessica Todd Smith, Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art. “Fortunately, longtime Huntington supporters Laurence and Carol Pretty shared our interest and offered the funds to make an acquisition possible. We’d searched for the better part of a year, and when this painting became available, we knew we had a winner.”

The crisp and painterly, straight-on view of a New York City hamburger stand bearing a sign reading “eat ‘n time” is a rare find. It’s an early work that was made just when photorealism was starting to take off.

Directly across from the Estes, another realist picture practically jumps off the wall and grabs you by the collar. The life-sized Dutch Still Life with Cyclamen (1980), by Paul Wonner, was painted with extraordinarily delicate details and takes the 17th-century Dutch still-life tradition to modern extremes. The tricky composition varies objects’ proportions—wait! Why is that wine bottle so tiny?—to remind us that the work may be realistic, but it’s not a photo.

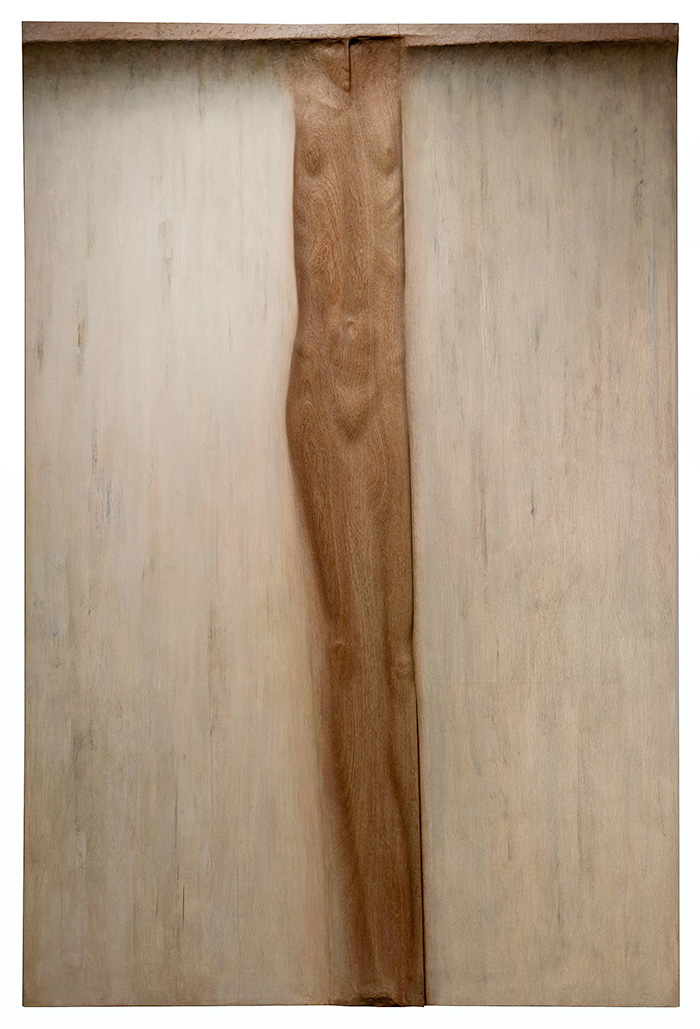

James Hueter, American (b. 1925), Thin Figure Rising, 1969, oil on wood, 72 x 48 in. (182.9 x 121.9 cm.), carved and painted wood panel. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of the artist. © James Hueter / Schenck Images.

James Hueter, American (b. 1925), Thin Figure Rising, 1969, oil on wood, 72 x 48 in. (182.9 x 121.9 cm.), carved and painted wood panel. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of the artist. © James Hueter / Schenck Images.Another striking piece in the room is James Hueter’s Thin Figure Rising (1969), which appeared in the 2011–12 exhibition “The House that Sam Built.” Hueter used soft pigment and the natural grain of wood to subtly reveal the emerging features of a female body. The result is an understated and powerful sort of crucifixion that has to be seen in person to be fully appreciated.

So, with selections ranging from the delicate and subtle to the crisp and real, this little room can satisfy a hearty appetite for the new—or for a burger with everything on it—in a single gallery through the end of April.

Thea M. Page is director of marketing communications at The Huntington.