Posted on Wed., Nov. 29, 2017 by

Jairo Perez, White Masked Ladrón, acrylic on canvas, 2017. This painting depicts a thief stealing a magnificent feathered cape. The cape that inspired the painting is on view in the “Visual Voyages” exhibition in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through January 8, 2018. Photo by Kate Lain.

To complement the exhibition “Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin,” The Huntington engaged young Angeleno artists, ages 18 to 26, to look at Latin America from their own viewpoints. Their paintings, prints, textiles, and mixed-media works comprise “Nuestro Mundo” (“Our World”), on view in the Brody Botanical Center, weekends only, through January 8, 2018.

“‘Visual Voyages’ ends with Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859,” says “Nuestro Mundo” curator Robert Hori, the gardens cultural curator and program director at The Huntington. “‘Nuestro Mundo’ brings that exhibition up to date through current work.”

All the “Nuestro Mundo” artists are mentored by Art Division, a nonprofit organization that trains and supports Los Angeles youth from underserved communities who are pursuing careers in the visual arts. About a year ago, “Visual Voyages” co-curator Catherine Hess connected with longtime friend Dan McCleary, founder and director of Art Division.

Luis Mateo, Hijo de Maíz, plaster sculpture, corn husk with human hair, 2017. The Mayan god of maize inspired this sculpture. Photo by Kate Lain.

The Art Division artists learned about the history behind “Visual Voyages” from Hess and about key objects in the exhibition from co-curator Daniela Bleichmar, associate professor of art history and history at USC. The artists also walked The Huntington’s grounds with Hori and Jim Folsom, the director of the Botanical Gardens, encountering many of the Latin American plants depicted in “Visual Voyages” along the way.

These experiences helped to spark the 24 artworks exhibited in “Nuestro Mundo.”

Hori says one of the most talked about works in the exhibition is Jairo Perez’s White Masked Ladrón, a painting that depicts a thief stealing a magnificent feathered cape—on view in the “Visual Voyages” exhibition—from the native people for whom it has sacred value. The thief leaves a trail of blood behind. Perez, in his artist’s statement, writes: “the theft of a culture . . . I feel that thought never went through the minds of the conquistadors; for them these relics were more of a status booster.”

The creative process led some artists to investigate family history and recall memories of the past.

Guillermo Perez, Sivar 1 & Sivar 2, digital prints, 2017. These prints represent the civil war in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. Photo by Kate Lain.

Luis Mateo fashioned the plaster sculpture Hijo de Maíz, inspired by the Mayan maize god, Hun Hunahpu. “Luis learned that his family was from Yucatán and probably has Mayan ancestry,” says Hori. Mateo employed colors of the Maya: green for jade, purple for cochineal dye and the colors of maize. He also cut off some of his hair to use in the sculpture. “In Mayan civilization,” Mateo writes, “long hair could raise an individual’s rank.”

Guillermo Perez’s Sivar 1 & Sivar 2 represent the civil war in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. “Each print depicts a different location and point of view of the civil war as seen through the eyes of my parents,” writes Perez, who had not discussed the war with his parents before he began making the prints. “The depiction of the military helicopter in both prints represents the constant reality of fear, danger, and uncertainty the Salvadoran people had to go through during this difficult period of time.”

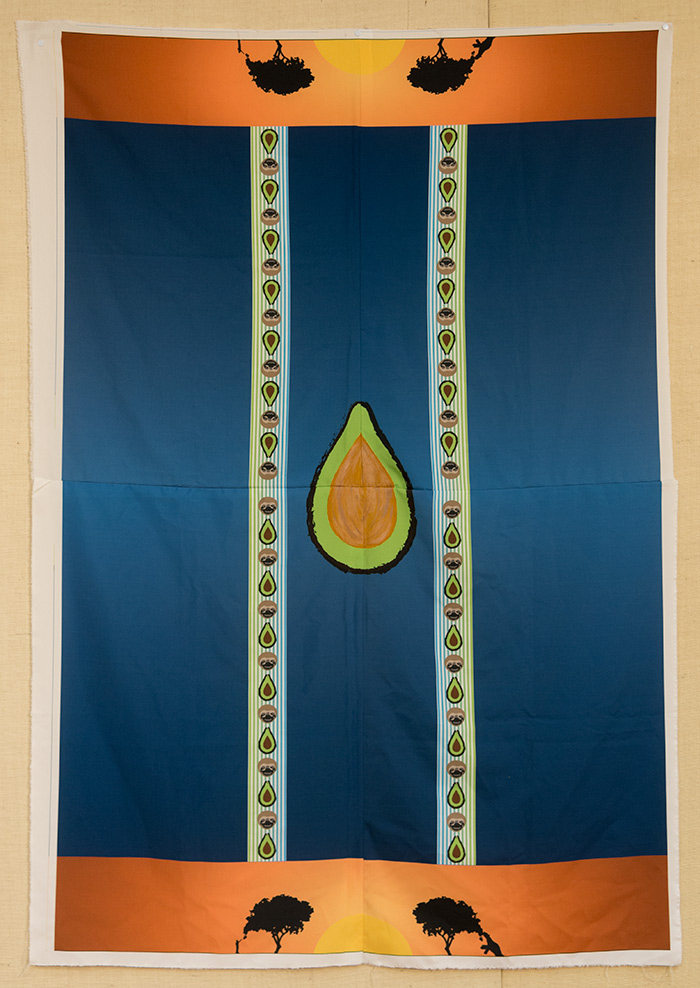

Alfredo Alvarado, Avocado Guayabera, printed fabric, 2017. Courtesy of ArtworxLA Fashion Design 2017 Workshop. Alvarado recalled picking avocados with his grandmother and used the fruit as a motif in this textile piece. Photo by Kate Lain.

Alfredo Alvarado recalled picking avocados with his grandmother and used the fruit as a motif in his textile pieces Avocado Pattern and Avocado Guayabera. Giant ground sloths also appear. Alvarado explains: “The giant ground sloth would eat the avocado whole and once the seed would pass, the seed would grow into a new tree.”

Today it is hard to imagine that, at one time, Latin American natives such as avocados, pineapples, and nopal cacti inspired awe and wonder among Europeans who beheld them in person or studied drawings of them in books.

Victor Reyes, Mission of the Humming Bird, linoleum print on paper, 2017. Reyes’s print takes inspiration from a Quechauas legend. Photo by Kate Lain.

The hummingbird, depicted in the title graphic for “Nuestro Mundo” by Victor Reyes, falls into this category, too. “Visual Voyages” features taxidermy hummingbirds among the animals in the foyer of the Boone Gallery. Color renderings of Mexican hummingbirds accompany an ornithological essay from the 19th century in the exhibition proper. Reyes’s linoleum block print, Mission of the Humming Bird, takes inspiration from a Quechauas legend: a flower courageously transforms itself into a hummingbird, moving a god to tears. The tears awaken a serpent, its wings shedding rain on the earth—saving the world from a terrible drought.

“I am delighted that these artists have provided us with a fresh, real-life perspective inspired by ‘Visual Voyages’,” says Hori.

To see images of all of the artworks on view in “Nuestro Mundo” and read statements by the artists, head to our Tumblr.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.